Enjoy

Blog

Contents

An Interview with Sian Torrington

August 26 2016, by Lara Lindsay-Parker

The 6:30am start, freezing temperature, wind (of course) and the potential to be very, very rained on did not deter the crowd. Braving a world outside of bed, around 70 people gathered on Courtenay place to witness Tiwhanawhana perform a dawn blessing of Sian Torrington’s latest project We don’t have to be the Building which is now being displayed in the Wellington City Council Lightboxes.

Image courtesy of Mark Tantrum.

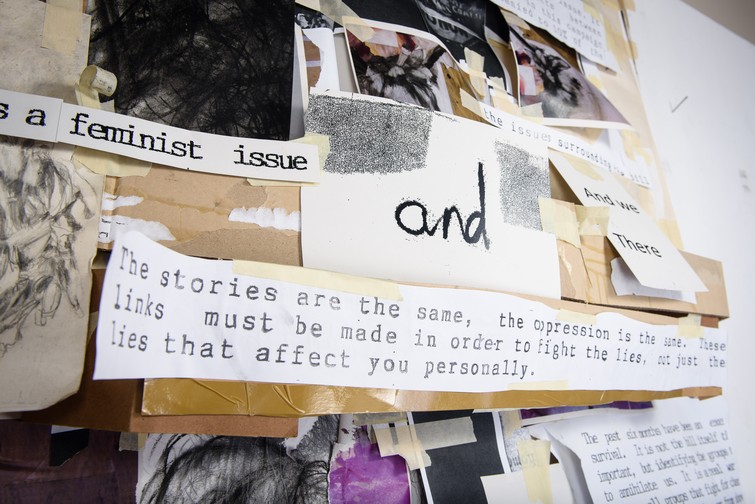

We don’t have to be the Building is (in Sian’s own words) about “gender, queer sexuality and embodied research… focusing on lesbian, bi-sexual, queer female bodied, trans* and female identified activists both 30 years ago during Homosexual Law Reform, and now in our contemporary world.”

I, in my most dishevelled form, was one of the many who had the great privilege of being present for the blessing of this project (I have my alarm clock to thank for that). I also had the pleasure of asking Sian a few questions about her work and she was very generous with her words.

Lara: What inspired it [the project] and how did the blessing and the project play into each other?

Sian: I’ve had these ideas kicking around for a few years--about trying to find ways to tell these stories through art work. I felt like I didn’t have the right to do that or know how would I do that but because this year is the 30 year anniversary of homosexual law reform, it was kind of like now’s the time, just do it. What enabled me to do the project is thinking about it as whakapapa—thinking about it in terms of who am I connected to, who’s already done this work and that it felt like it was okay for me to be searching, to at least be searching and asking questions. People could choose to be involved or not be involved, so the whole project was based on this fully informed consent model of you can say yes at any time, and you can say no at any time. And that made me feel okay about asking for people’s stories and engagement. I was trying to step away from making something happen in a way, just trying to be really accepting of what happened or what was offered. I thought a lot about how every part of the project was like an offer and a response. Offers from me--and I didn’t know if they were the right offers or what--but just having a sense of, well, if they’re not the right offers, I’ll find out because people won’t want to do it or they’ll say no.

Through the research, which happened in a number of stages—I did research in LAGANZ (Lesbian and Gay Archives, held in the National Library) and at various community engaged events where people came and were drawn or they came and told their stories—I started to realise that the project was a lot about solidarity and sticking together, or how we do stick together and how we don’t. One of the really huge things that I found in the archives, and I didn’t really understand the enormity of it, was about the exclusion of bisexuals (women in this case) in the 80’s from lesbian run spaces and from women’s spaces and the impact of that is still in our communities now—the pain of that. It started to be a much deeper project than I had anticipated… about how do we accept each other at the same time as being different and sometimes having conflicting needs—but how do we hold those with compassion? The whole community is such a small community; to me it’s more important that we find ways across—whatever those ways look like. Rather than (and I got this looking at the archives and the history) just excluding people because the conversations that you have to have are hard and painful and frightening and all of those things. In the long term, looking back over 30 years, it’s never worth it—the pain that that causes everyone resonates. It goes on and on and on.

So in terms of the blessing, that was about asking for support. This project took around 9 months of actual making and directly involved around 100 people. It’s a huge amount of stories and weight to have been holding and transforming and listening to. Usually with a show I have just enough energy to make it through an opening and then fall over, but with this show when I got to the end of the making and I thought, “I am not able to do this alone. I have to have help.” It needed to be a pretty big, serious event to lift the tapu on the work and to put that work onto the street—it’s a huge deal. The people whose stories, whose bodies, whose images are on that street—it’s an incredibly brave, momentous thing to do so that had to be held with a lot of care. Tiwhanawhana did that blessing and I went to them and I said “I don’t know what I need, I don’t know what I’m asking for, but I need you. Will you be with me?” And I was looking for a queer, trans* whakapapa. I went to my elders and the people who know how to do that work and who have that cultural wisdom and asked if they could please help me. So for me, that blessing was a really incredible moment of being supported. Every photo that I’ve seen I am just surrounded by people; always there are people behind me that have my back. The Welsh waiata was about me reaching for my blood line whakapapa across breaks in my family, across breaks with my immediate parents. My dad is Welsh so it was a way—through song, through waiata, through that wisdom—to connect with those things through creative means.

It ended up feeling like a sort of exchange of vulnerability. I don’t speak Welsh, that’s the first time I’ve ever tried to say those words and that in terms of Tiwhanawhana, that’s an experience that many, many Maori unfortunately have because of colonisation; having to learn your own language.

Tiwhanawhana performing at the dawn blessing. Image courtesy of Neil Price.

Lara: Having described the project as ‘an exchange of vulnerability’ and considering the general culture of Courtenay place, did you have any anxieties about it being in that particular area in the city?

Sian: Yeah. It’s a place where a lot of us have experienced abuse—of all sorts. And this is a way of speaking back to that. What is important to me is everyone being together; physically, the work being together and spiritually, bringing everyone who was involved together. The reason they’ve said, ‘yes, put my image of my naked body on Courtenay Place’ is because they really believe in the kaupapa and what that project is trying to do. I don’t know if they’re going to be graffitied but the good thing about the light boxes is they are council owned, and I think they’re pretty indestructible and whatever happens to them is going to be cleaned off very quickly.

Dawn blessing hikoi. Image courtesy of Neil Price.

Lara: Does that make you feel powerful? Having the council on your side, is that the best feeling- just feeling supported?

Sian: Yeah, I said to Tiwhanawhana last night that I have never felt so supported in my life as I did that dawn blessing because it was support that wasn’t just from my partner or my close friends. Some of those people I have only known over the last couple of weeks. I think a lot about community and what does that mean? What does it mean and when does it kick in? There was a moment where people held me because some of them knew me, or because some of them just heard what I had to say, heard those vulnerabilities and heard their stories too and thought we’ll stand with you. So yes, it’s pretty extraordinary. I wouldn’t say it makes me feel powerful because during this project I have never felt so vulnerable in my life as for the last 9 months. And it’s just gone on and on and on. So it’s more that I felt… desperate for that kind of support. And when it came, it was like being carried in there. This project has felt like being a vessel, I’ve never felt more in service to my community. It’s like whakapapa. It’s about me and it’s through my instinct and my connections that I created this—but it doesn’t belong to me.

Lara: How did the editing process go when you’ve just got so much content to work with? How do you choose what to present?

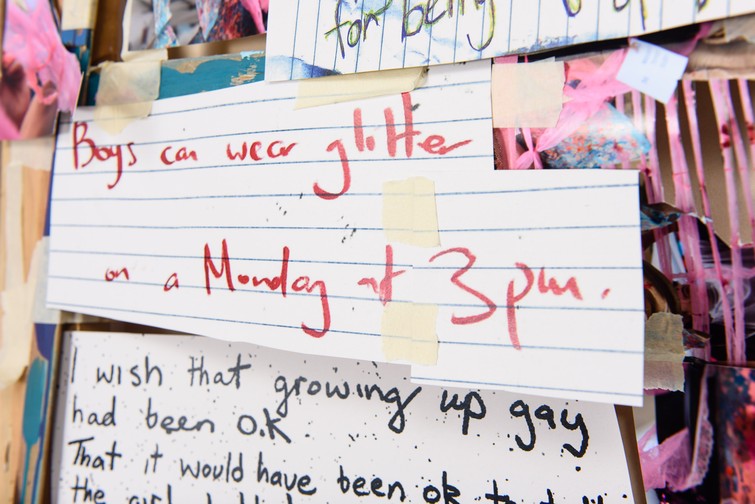

Sian: I work quite intuitively and there were key parts. I tried to keep the stories with their own integrity. The first lightbox is about whakapapa; it’s about beginning that search. And for the second I looked at the archives and edited them in relation to the research in a way. There’s one panel which says ‘I wish.’ That’s from Out in the park and I certainly had moments where it felt like just material the archives could have filled up 50 panels. But I just went over and over it, refining it and deciding which voice needed to be the loudest. In terms of quotes from the archives, looking at who’s saying something that encompassed a lot? Like the quote in that second panel about solidarity, just that, says so much.

Image courtesy of Mark Tantrum.

Lara: Did you have any goals for this project beyond what you presented in the light boxes?

Sian: My intention, once they were up, was always to develop a hui around queer activism, solidarity, survival and creative practice. That’s something that I want to be really active. It won’t be sitting down listening to speeches, it’ll be doing workshops, it’ll be some presentations and it will involving people and learning from each other. Other than that, I’d like to make a publication. Potentially bringing together stuff that comes out of the hui with the project. Also, it’s made me think a lot about what my job is as an artist, what am I doing? It’s really taught me that what I have to offer is, and can be like, a service which really does something—one that’s genuinely useful in terms of peoples healing. So I’m interested in continuing to find ways to provide those services—whether it’s running workshops, facilitating other people making stuff or storytelling, listening and reflecting back through drawing. I feel like in the past and in indigenous cultures now, artists have a job as part of a society. There are things that we can’t say in other ways that we can say through movement, through film, through dance, through whatever—I’m interested in developing that.

Lara: What about people outside of the community the project is about? How do you make it so they will engage with it? How do you facilitate that?

Sian: Watching people and how they’re interacting with the lightboxes--it’s really cool how people are going in and reading. One of the panels that I think is the strongest in terms of that is the ‘we wish’ one. What people say is just so human—anyone could say those things and a lot of those messages came from really young people. I think you can tell that just in the language they use or the way that they write and I kind of find it hard to believe that most people would not be touched by some of those sentiments. I also tried to be really as brave and direct as I could be. My partner works in editing and writing and they say to me, “Just say what you mean. Say what you mean.” And this project was really trying to not be cool, not be clever about it, and just go this is what I actually mean. At lots of points felt really, sickeningly terrifying but I do believe that when you do that, that it resonates with people of various differences. I think it’s very human. Our whole world is made of stories and stories about identity so yeah, that’s my hope, that these stories resonate with people.

For more information on this project visit www.wedonthavetobethebuilding.tumblr.com and http://allmeaningisthelineyoudraw.wordpress.com. We Don’t Have to be Building is supported by the Wellington City Council Public Art Fund, Creative New Zealand, Rainbow Wellington and 78 Boosted supporters.

Sian was also a part of Enjoy Feminisms, November - December 2015.

You can also read her contributions to Enjoy's Occasional Journal here: