Enjoy

Blog

Contents

Snapshot #1: Artists at Work: The STAFF Project

December 20 2018, by Imogen Simmonds

Archives and library intern Imogen Simmonds has spent the year cataloguing Enjoy’s archive. In this series of blog posts, Imogen reflects on interesting moments from Enjoy’s 18-year history, and considers how our past projects have helped shape who we are today.

Enjoy is more than just a name. It’s a mood, a mission statement, an instruction. It promotes an active, informal way of engaging with artworks. It asks those who venture into the gallery to question, explore and immerse themselves. It conveys the attitudes of the organisation’s founders, framing their vision. Above all, it asks us to soak up and savour a palpable sense of fun.1 The maxim has attracted likeminded practitioners and set the tone for exhibiting artists since Enjoy’s early days, and Enjoy’s archive really underlines this. Brimming with immediacy and a light-hearted energy, the archive defies notions of such records as sterile and inhospitable, documenting an array of playful approaches over the years; the early 2000s in particular were characterised by works with a sense of humour. Bex Galloway and Sarah Miller’s STAFF (Starving Tortured Artists and Friends Fund) project (2004), part of Enjoy’s inaugural Performance Week, illustrates this.2

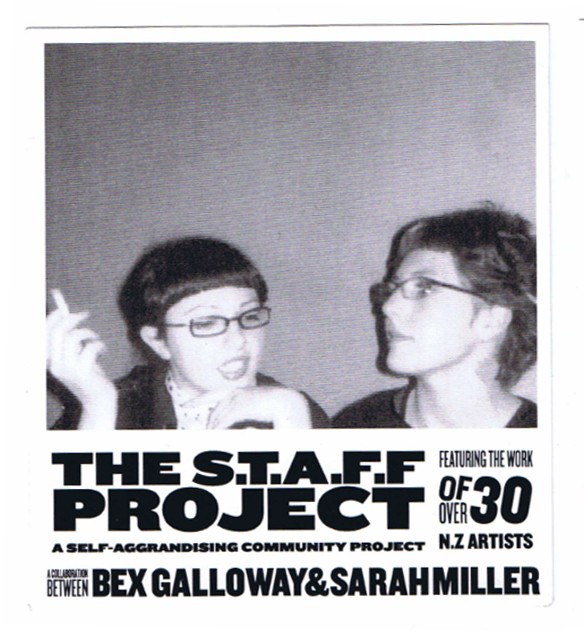

Bex Galloway and Sarah Miller, promotional postcard for The STAFF Project, 21 August – 18 September 2004. Image courtesy of Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

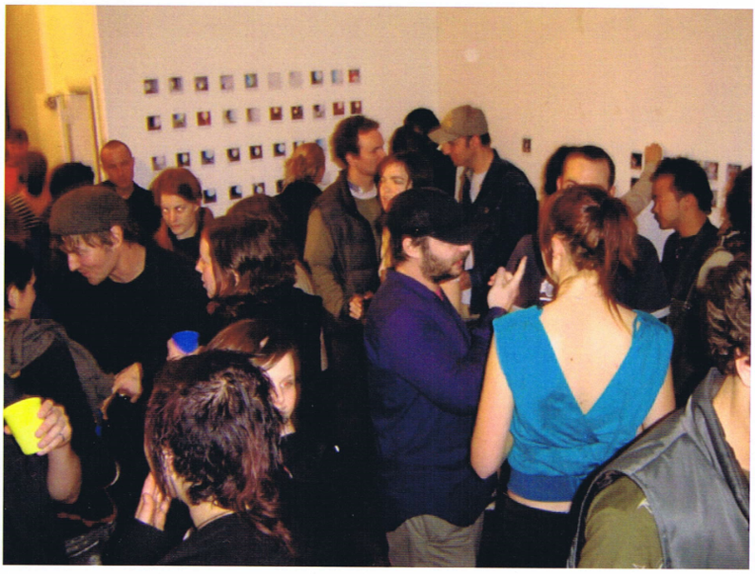

For this extended performance piece, more than thirty curators, commentators and artist-activists, marshalled by Galloway and Miller, participated in three fundraising enterprises: a car wash, a street appeal and a good old-fashioned bake sale. As proudly publicised, all proceeds went towards buying Polaroid film that was doled out during the project’s one-night finale at the gallery. Here, the gleeful arts professionals gathered to document their efforts through an exhibition of instant photographs of one another. Envisaged from the outset as deliberately “narcissistic” and “self-aggrandising,” what differentiated this project from the fundraisers it imitated was its tongue-in-cheek nature. As Galloway joked at the time, the project was about “artists working together to support their egos.”3

Far from being a frivolous vanity project, this self-reflexive and relational performance strategy attracted both Te Whanganui a-Tara Wellington’s public and its more actively engaged arts community. Through political discourse allied with noughties articulation of 1970s post-object ideals—a movement epitomised by staged events that asked audiences to think critically about context-specific ideas and experiences centred on subjectivity and the social—the STAFF project used humour as a vehicle through which to critique the status quo.4 By putting a playful spin on proceedings, the project’s interpersonal approach involved audiences in an accessible and non-confrontational way. Riffing off the trope of the “self-involved artist,” STAFF performers challenged conventional expectations of and assumptions about art: foremost the idea that the discipline takes itself too seriously. They offered the olive branch of comic relief and, in doing so, dissolved barriers between parties and fostered the sense of a shared joke. 5

The STAFF project explored issues of gender, labour and remuneration in the arts which remain relevant today. Questioning the precarious conditions and boundaries within which contemporary artists operate, the work went beyond celebrating the creative community to address the unstable economic terrain its members continue to navigate in a capitalist society. Produced during a period immediately preceding global recession, STAFF spoke to the socio-economic systems and institutional structures that keep most artists broke.6 Appeals for petty cash to cover the project’s material costs highlighted a system which still necessitates practitioners work for free or next-to-nothing, pool resources and constantly justify their existence. In satirically performing widely accepted manifestations of labour—cleaning, cooking, customer service—the participants underlined their artwork as work. They questioned a society that devalues artistic labour, subscribed as it is to the myth of “artistic purity,” the belief that art is a “calling,” a vocation which should exist outside the market.7 It is no coincidence that the only tangible outcome of the project was a visual record of its participants; its human capital.

In presenting themselves as overblown caricatures of 1950s housewives at their bake sale (beehives and all), Galloway and Miller additionally spoke to a history of unacknowledged and unpaid labour by women in both the domestic and professional spheres.8 The artists shone a light on exploitation, emphasising the fact that nobody, not even artists, can escape capitalism.9 Through parody, they navigated uneasy conversations about their own labour to expose the absurdities and indignities of their circumstances. An act of collective self-empowerment, the project constituted a refusal on the part of the artists involved to be barred from the politics of their subjugation. By underlining the self-sustaining nature of Enjoy’s creative community and consolidating it, by pivoting round humour and depending on public contribution, the project welcomed all who shared the “joke” into the community.10

STAFF Project Polaroid night, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Friday 24 September 2004. Image courtesy of Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

Satirical projects like this, particularly those which address the artist in context and appeal to a sense of collectivity, have been vital in Enjoy’s process of self-definition. They mesh well with the organisation’s commitment to giving artists the space, support and resources to create experimental and potentially controversial work without commercial constraints or pressures. Regan Gentry’s then-ongoing project Foot In the Door (2004) was another example of such a work. He too used humour to address the struggle faced by emerging artists in a highly competitive culture. Considering institutional power and a gallery’s ability to “make” practitioners, Gentry installed a one foot ruler in Enjoy’s front door as a visual pun. The institutional backing lends the work credibility, both highlighting and critiquing the power relationship between artist and gallery. Other artists championed by the organisation have relied less on humour as vehicle and simply revelled in absurdity. Tao Wells and Ryan Chadfield’s proposal for their “competitive” exhibition (2–20th March 2004) is a terrific illustration of this. Weirdly wonderful, this hodge-podge of whacky ideas and surreal imagery really captures the atmosphere of the epoch.

In the fourteen years since the STAFF project, Enjoy, like the world around it, has transformed. In a context of greater professionalisation where understandings of what it means to be an artist are expanding, the gallery’s exhibition programme has developed and shifted in tone. Where humour is employed, as in Isabella Dampney and Theo MacDonald’s Heart of Glass (15 March – 7 April 2018), a familiar playful energy floods back. As with the STAFF project, the work cheekily played on people’s expectations of and assumptions about art and those who produce it. Considering how we “relate to and understand contemporary art,” the pair shattered one of the gallery’s windows and invited the public and mainstream media to respond to their gesture. In this instance, it was the audience who laboured for the artists’ cause with one Johnsonville resident questioning whether the artists should be paid for the work.11

-

1.

Mark Amery, “Fresh Exploration of Aural Space,” The Dominion Post, June 17, 2005.

-

2.

The project took place between 21 August and 18 September, 2004.

-

3.

“Let them sell cake,” Capital Times, 1 September, 2004, 3.

-

4.

Christina Barton, “Post-object and conceptual art,” Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed 14 November, 2018, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/post-object-and-conceptual-art/print%20.

-

5.

Sue Gardiner. “Fun-damental Art,” Art News New Zealand Summer 2005, 59.

-

6.

William Powhida, “Why Do We Expect Artists to Work for Free? Here’s How We Can Change the System,” Creative Times Reports, accessed 2 November, 2018, http://creativetimereports.org/2014/12/02/william-powhida-why-do-we-expect-artists-to-work-for-free.

-

7.

William Powhida, “Why Do We Expect Artists to Work for Free? Here’s How We Can Change the System.”

-

8.

Tom Hunt, “1970s’ cake stall and Polaroids to Enjoy,” The Wellingtonian, 23 September, 2004, 36.

-

9.

William Powhida, “Why Do We Expect Artists to Work for Free? Here’s How We Can Change the System.”

-

10.

Enjoy Public Art Gallery, “Enjoy Performance Week,” press release, September, 2004.

-

11.

Jo Mells, “Our Hollow Consumer Culture,” letter to the editor, The Dominion Post, March 31, 2018.