Enjoy

Blog

Contents

Areez Katki's reading list

March 17 2021, by Areez Katki

This reading list was compiled by artist Areez Katki alongside the exhibition History reserves but a few lines for you at Enjoy (19 Feb–3 April 2021).

The texts below have been instrumental to the artist’s research and practice, with many works in the show responding to the poems and themes of the titles below.

Beginning with O, Olga Broumas

Born in Ermoupoli, Greece, Olga Broumas wrote this book of poetry in 1977 as a queer migrant, living and studying in the United States. The book was published around the time she began writing in English instead of her mother tongue.

This cultural transliteration is offset by how Broumas’ work looks to her homeland for classical cues, particularly through the traces of sensuality present in the lyrical fragments of Sappho. It is remarkable how the explicit sexuality in Broumas’ work underpins the poem as a gesture, or message, which presents themes of longing, grief and states of ecstasy.

Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson

The term, “Bittersweet” is here extracted and translated by one of my favourite poets, Anne Carson, from the term Glukupikron that was created by the archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho. “Bittersweet” is how she described Eros. Now, there’s a lot of Sappho in this reading list, and I’m well aware of how she manifests frequently in my work.

Here, Anne Carson takes the concept of bittersweetness to examine the complex phenomenon of Eros—a potent love exemplified by a simultaneous experience of pleasure and pain. For a further (and queered) reading of this concept, one might also look at Anne Carson’s ground-breaking novel in verse, Autobiography of Red—a stunningly tender and intuitive work. Red has ferried me through some of the strangest experiences, which honestly, require finesse like Carson’s to describe.

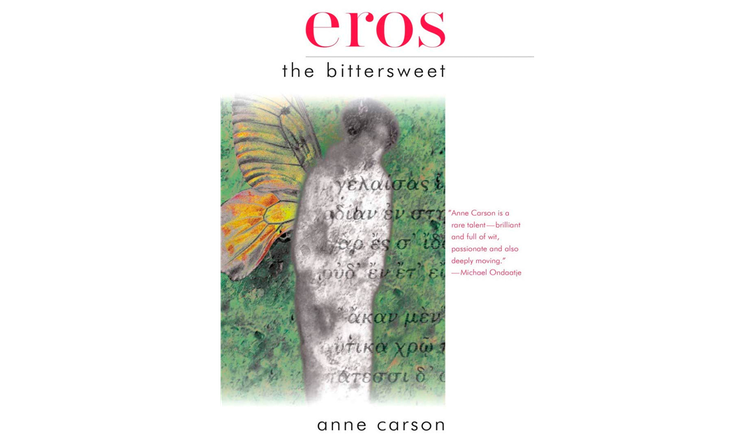

If not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho.

Translations by Anne Carson

Translated, intervened with, reframed and annotated by Carson, If not, Winter is an altogether new reading of Sappho’s complete works. Having lived on the island of Lesbos between c. 630–c. 570 BCE, Sappho’s poetry transcends time by presenting universal themes that deal with the human experience. Almost all of what remains of Sappho’s work are soft lyric fragments. The only complete poem is her “Ode to Aphrodite.” Carson commits to the fragmentary aesthetic (more on this later, with Page Du Bois’ Sappho is Burning) by employing the use of square brackets and space on the page—recreating holes from the original papyrus manuscripts, while also allowing us to read, literally, new meaning into an ancient language:

someone will remember us / I say / even in another time —Fragment 147

Selected Poems, Constantine P. Cavafy.

Translations by David Connolly

There’s a lot that I could say about Constantine P. Cavafy’s life in Alexandria and the sensual work that he produced in the early 20th Century. I’ve relished Cavafy’s poetry for its lush tone, its wit and humour, which sticks around even when it is translated. Also, a penchant for layering history with the personal and deeply desirous queer gaze.

This is a copy of selected poems that I purchased in Athens a few years ago. The works span most of the early 20th Century, and include Connolly’s translation of “Caesarion,” which is where this exhibition’s title comes from.

An additional note about “Caesarion”: the poem was supposedly gifted in 1918 by Cavafy to a fellow Alexandrian Greek, Alexander Iolas, who would go on to be an influential queer art dealer and collector. Iolas was responsible for cross-pollinating art between Europe and the USA at the height of modernist and surrealist movements. Although he was instrumental in the careers of figures like Ernst, De Chirico and Warhol, history has not reserved much space for his legacy.

Sappho is Burning, Page DuBois

Our disruptive “Tenth Muse,” Sappho, appears again—she is used here by Page DuBois as an example that challenges Western conventions of sexuality, language and power.

Her inassimilability is used as a keystone to examine alternative modes of storytelling and history-making. This queering of culture, by looking toward the East through poetry and language, is one of the finest legacies of Sappho. DuBois’ writing examines the effects of this fragmentary world and its aesthetic output; how Sapphic poetry sits at the very origin of the Western civilisation, but simultaneously inhabits a space outside of its reductively linear accounts of history.

Sufiana Poems, Hoshang Merchant

While I was researching the intersections of Parsi and queer histories during a residency in India, there were two figures who surfaced repeatedly over the scant search results for queer forebears with the same ethno-cultural heritage as myself: Hoshang Merchant was one of them; Farrokh Bulsara, aka Freddie Mercury, was the other.

Merchant was born in 1947—the year of India’s independence—in an upper-middle class Parsi family. He proclaimed his queer identity very early in his life, at a time when it was a criminal act to be gay in India. These poems, albeit very late in his career as a theorist and poet, arrived after he edited and published the first anthology of queer writing from South Asia (Yaraana, 1999). While Merchant’s Sufiana poems tend to hold socio-cultural and religious constructs at the forefront of their causes, they address queer identity and Parsi identity in a way that feels empowered and unapologetic. I have felt thrilled, confused, angered, often all at the same time, by his work.

The Man Who Would Be Queen, Hoshang Merchant

Merchant’s intensity is amplified in The Man Who Would Be Queen. The autobiography is part manifesto, part woeful stream-of-consciousness rambling. At its best, the book is entertainingly poignant, at its worst, The Man Who Would Be Queen is infuriatingly elitist.

From this book I’ve learned valuable lessons about the deepened complexities within the intersections of queer identity. The privileged class that his Parsi heritage afforded Merchant is something uncannily analogous to the whitewashed eurocentrism that often characterises contemporary queer discourse from the West. That being said, it was an insightful read—once I realised how Merchant is himself a product of systemic issues linked to a toxic heteropatriarchy. How he writes in his own unique, brave—often deliciously crass—way, to challenge the hegemonies of identity and representation.

Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, José Esteban Muñoz

A seminal text that blends the essayistic musings of Cuban American theorist José Esteban Muñoz with a manifesto-like tone of urgency. Cruising Utopia provides a reading of queer identity that stands at the bursting-open intersections of culture to offer, “alternative mappings of queer life in which questions of race, class, gender, temporality, religion, and region are as central as sexuality.”

The text was, and continues to serve, as one of the most insightful readings that enrich my exploration of intersectional, migratory and queer identities.

Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Ocean Vuong

There are few contemporary poets I’ve read who’ve managed to encapsulate the turbulent disorientation of the migrant’s experience—written in a way so tender and delicate that we often forget the violence that is at the core of Ocean Vuong’s work. The language employed by Vuong in this selection of poems manages to disentangle many of the traumas that lie at the core of the queer and migratory intersection, yet, Vuong manages to create a healing forcefield around this reader. So much so, that three of his poems have been employed to serve as subject matter with which I created new ekphrastic interpretations on my own delicate ground material: cloth, specifically square muslin handkerchiefs that I inherited from my grandmother.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong

The layered and lyrical aspects of Vuong’s writing are here captured in novelistic form. Officially, it is his first work of fiction, though On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is essentially a genre-defying hybrid work, framed largely as a letter to his mother. It also crosses genres due to its disjointed, autobiographical and poetic forms. It is a violent, tender, humorous and breath-takingly rich experience to read.

The epistolary mode undulates between three main storyline threads: a gentle but assertive voice addresses his mother, who never spoke English, as the narrator shares their family history as migrants in contemporary America; a more passive, distant, third-person narrator gives us glimpses into the world of his mother and grandmother during the Vietnam War; a third, lyrical voice speaks of his blossoming queerness, of growing up in rural Connecticut, USA. The overarching theme of violence is peeled and exposed until we can see its soft underside, a revelation of how sensual and fragile it can be.

Areez has generously loaned his personal copies of these books to Enjoy’s reading room for visitors to browse through during his exhibition.