Enjoy

Blog

Contents

Help Yourself introduction and reading list

June 02 2021, by Grace Ryder

This introductory essay was written by Grace Ryder for Help Yourself an exhibition co-authored by Turumeke Harrington and Grace Ryder with Sarah Hudson, Saskia Leek, Kristin Leek and Greta Menzies (28 May-10 July 2021).

The reading list that follows includes texts referenced in Ryder's writing as well as readings and books instrumental to Harrington and Ryder's respective practices, their friendship and their collaborative work devising Help Yourself. Copies of these texts are available in Enjoy's reading room for the duration of the exhibition.

Help Yourself

In Jia Tolentino's essay Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman, she writes:

...it’s very easy, under conditions of artificial but continually escalating obligation, to find yourself organizing your life around practices you find ridiculous and possibly indefensible. Women have known this intimately for a long time.

We all experience this ridiculous and indefensible pursuit of the ideal version of ourselves under patriarchal capitalism. I’m sure reading this you’ll think of all the times you’ve ricocheted, double-bounced between multiple, simultaneous roles, performing forty-eight hours of work in a twenty-four hour day. If you’re like me, this will present as a visceral feeling of self-reproach, a sick, dry mouth, and a reminder to yourself—I won’t do that again.

Helping oneself is to take as much as one would like, or to take something without permission. “Help yourself" is a term of manaakitanga, inviting others to make themselves at home. You can help yourself to another serving or help yourself by engaging a therapist. “Help yourself” evokes a notion of self-love, a regard for one's own happiness or advantage. It’s a generous and selfish term, either way it’s the one part of self-care that I’m into. Help Yourself begins with this gesture of generosity. Take what you will from this. Please, help yourself.

This exhibition is co-authored by Turumeke Harrington (Ngāi Tahu) and myself (Pākehā; Polish, British), created for each other—selfish and intentional. We offered each other conditions to work that avoid and deter the ridiculous and indefensible aspects of "normal" practice. Turumeke claimed her lust for making without the need to administrate and theorise. I wanted to read, as much and as broadly as I could. There is still the unavoidable deadline of an opening and the pressure to create work that has meaning, but here an extended period of trust and experimentation results in an exhibition that cradles and nurtures our ambitions.

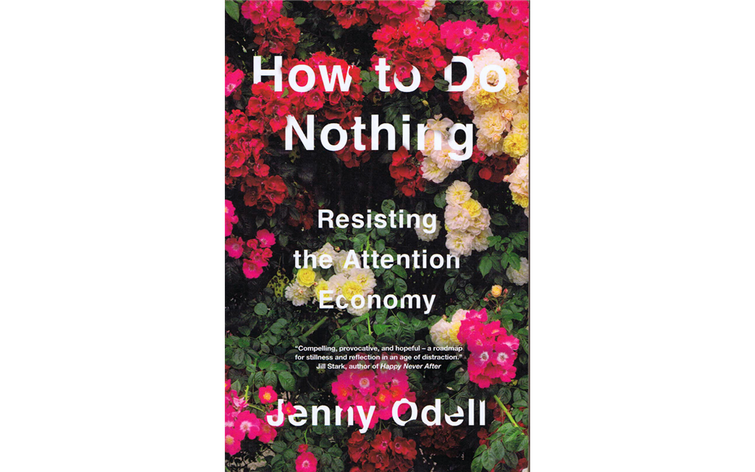

By living and working together, Turumeke and I have optimised our output and our time. Optimisation is the process of making something as fully functional, perfect and effective as possible. We have co-opted the optimisation of efficiency, life-hacked it, if you will. Not pushing the other to Tolentino’s ridiculous and indefensible perfectionism, rather gently guiding each other to seek more effective, more pleasurable experiences in art and life. We do a lot together, often because we enjoy each other's company, but also because it makes life a little easier. We share resources and time—food, school-pick-ups, driers, tools, materials—enabling the other to achieve more or direct their attention better. We offer support, accountability, criticism and perspectives at times when others don’t or can’t. Jenny Odell’s book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy suggests:

...we take a protective stance toward ourselves, each other, and whatever is left of what makes us human—including the alliances that sustain and surprise us. I’m suggesting that we protect our spaces and our time for non-instrumental, non-commercial activity and thought, for maintenance, for care, for conviviality.

This series of suggestions best matches how Turumeke and I work and live together.

Our relationship is not unique—we were invited to exhibit by another ambitious and intelligent friend, and developed this exhibition with many others in mind. There are many presences here with Turumeke and I—our friends, Sarah, Saskia, Kristin and Greta, our families, our tūpuna, our inspirations, our colleagues—the company we keep. They direct our attention to mutual support as a guiding inspiration in life and art, a vital aspect to community building, and a form of survival outside the bodily self.

Turumeke’s installation—banners, sconces, and reading chairs—is very her. There is a colorful palette, blue (my favourite colour), chairs (her’s & her’s), nylon, steel and plasticky-looking fabrics. There are beings, biologically human (genital forms and mouths) or celestial. Nods to her daughter, parents, siblings, partner, friends and peers always show up one way or another in Turumeke’s work. I like to think of these works as her guardians, or the guardians of our friends with her banners operating as their protectors and guides.

Together in the backspace are works by Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pūkeko, Ngāi Tūhoe), Kristin Leek (represented through her daughter Saskia) and Greta Menzies. Expanding our ambition to include others, we invited these makers to create a work for Help Yourself, under one condition: to create something, anything, that is for someone else. It could be intended as a gift, dedicated to, or inspired by them.

Sarah has understood the significance of collaboration for a long time as part of Mata Aho Collective. She is also a part of Kauae Raro Research Collective where they develop and share knowledge on customary art practices, materials and techniques, learning and creating together. Sarah’s work Reunion (2021) is for a fellow collaborator. The two met through making and found they closely shared whakapapa. Sarah brings the whenua of their shared tūpuana into the gallery. Ngāti Pūkeko whenua enriches and colours fabric that literally holds Ngāti Maru ki Hauraki whenua in a sling, or perhaps a flag, symbolic of all that is shared between them—tūpuna, friends and collaborators.

Greta Mezies is a long-time friend of Turumeke. I came to know and admire her work through the pieces that live in Turumeke’s house. Joining our open-ended exercise Greta created two talismans, both ascribed with magical powers intended to protect and heal the individuals for whom they are made. They act as cosmic forms inviting the world that extends beyond and between various minds and bodies. As with Turumeke and Sarah, Greta’s work evokes a sense of liminality, where the self and others blend.

Finally, there is my friend Saskia Leek with a work by her mother, Kristin Leek. In 2019 it seemed Saskia couldn’t catch a break, worrying about the well-being and health of her parents was relentless. I recognised this from seeing my own mother’s experience with my grandparents. When we invited Saskia to contribute to this exhibition, she was working through Kristin’s belongings after her death, slowly and carefully excavating a lifetime of creativity. Presented here is one of Kristin’s wall hangings accompanied by Saskia’s writing.

I think of Saskia’s contribution to this exhibition as a gift to us, to Kristin, and to herself. While honouring Kristin’s talent, it also cradles Saskia’s grief. Consider also Greta’s vessel, Sarah’s whenua, and the celestial beings in Turumeke’s installation—these objects, like Kristin’s wall hanging, create an opportunity for collaboration between places, times and friends “in the present as well as in the past”.

The act of centering friendship and collaboration as a manner of working may appear overly sentimental. But the opportunity to build them, to operate within them as an act of resistance to the ridiculous and indefensible has become vital to sustainability and prosperity for us. It does, as Arendt and McCarthy knew well, create “a fundamental aspect of personal support, a condition for doing things together”. Help Yourself is an exhibition which has developed out of a simple exercise in support, care, sustainability, friendship and love—alliances that sustain and surprise us.

Reading List

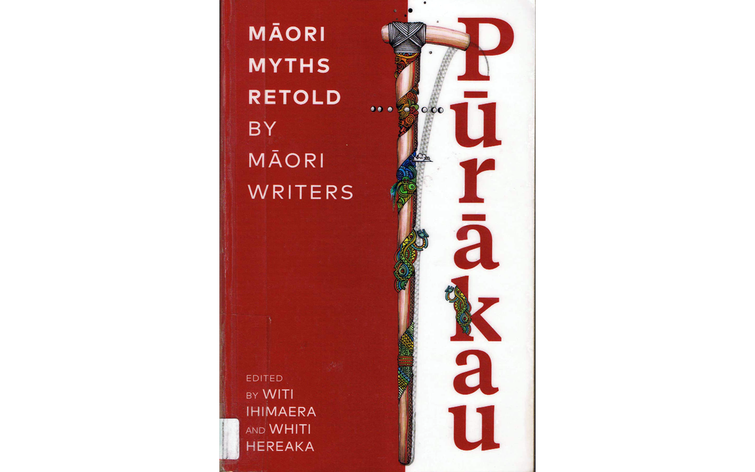

Witi Ihimaera and Whiti Hereaka, Pūrākau: Māori Myths Retold by Māori Writers. Random House New Zealand, 2019.

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House, 2019. (Recommended by Matilda Fraser.)

Jan Verwoert, “Exhaustion & Exuberance: Ways to Defy the Pressure to Perform” in What’s Love (or Care, Intimacy, Warmth, Affection) Got to Do with It?, edited by e-flux journal. Distributed for Sternberg Press, 2017.

Celine Condorelli, Too close to see: a conversation with Johan Frederik Hartle, Originally published in Self Organised, Open editions, 2013. Via On Friendship, Rebecca Boswell.

Céline Condorelli, Support Structures, A co-production with Support Structure: Céline Condorelli and Gavin Wade with James Langdon. Published by Sternberg Press, 2009

Jia Tolentino, “Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman”, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, HarperCollins Publishers, 2019. (Recommended by Turumeke Harrington.)

Witi Ihimaera, Pounamu Pounamu, Reed New Zealand, 1972. (Gifted by Tia Pohatu, Christmas 2018.)

Marilyn Waring, Still Counting: Wellbeing, Women’s Work and Policy-making, BWB Texts, 2018.

Sarah Hudson, Mana Whenua, self-published, 2020. (Contribution from Claire Harris.)

bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions, William Morrow, 1999. (Contribution from Vanessa Mei.)