Enjoy

Blog

Contents

DOWN TIME: Labour politics, subjectivity and counter-production

July 18 2017

There are many points of entry into labour politics. That is the nature of advanced capitalism. Labour has become first nature and our existence demands that we participate in its politics. Yet this ‘we’ is overwhelmingly singular. Representation is exclusive, marking difference invisible or incomprehensible through the lens of the dominant culture. The knowledge of a reduced and individualised subjectivity is being produced elsewhere, sold back to us, transformed beyond any reconcilable image of our own realities.

The issue is disruption. Especially in this social and economic moment. With workers’ rights being taken away, the bargaining power of unions diminished and corporations growing increasingly stronger, where is there, at the very least, some intervention or mediation? Usually, the mainstream narrative is reactionary. How can we adapt? How can we consume better? How can we be simultaneously as productive as possible while remaining alienated from what we produce or the means we produce things by? Intervention is rarely framed as counter-production in mainstream discourse.

Deborah Rundle’s exhibition DOWN TIME, at Wellington artist-run gallery play_station, is concerned with this counter-production. While all people are implicated in the production and reproduction of subjectivities, the artist’s role is especially involved. This is something that is distinctly lucid in Rundle’s practice. It also highlights how her practice can be viewed as a mediation of subjectivity. Within DOWN TIME, one theory that emerges as influential to this mediation is Antonio Gramsci’s notion of ‘common sense’. Gramsci asserts that dominant knowledge, culture and interests have become accepted by a majority of the population as incontestable truths—the spontaneous, everyday embodiment of discourse.1 Yet within this, Gramsci—who was not a populist—saw the potential for ‘organic intellectuals’ to formulate a new, counterhegemonic ‘good sense’. Drawing on Gramsci’s emphasis on practicality, Rundle locates art as another site for the everyday counter-production of good sense.

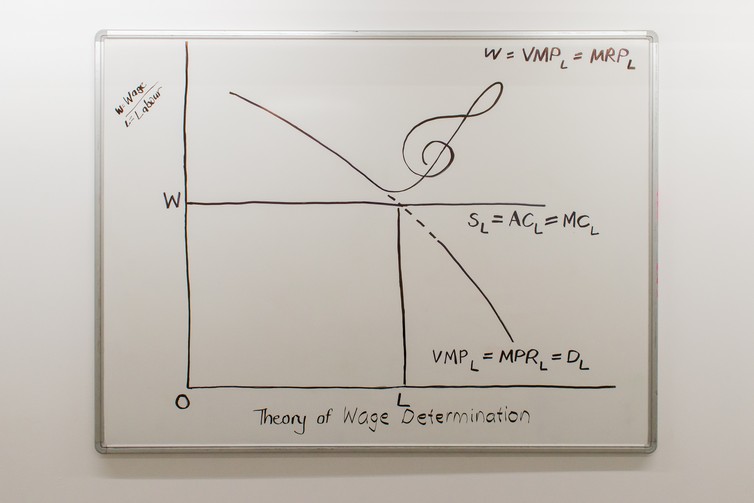

Deborah Rundle, Counterpoint, 2017. Image courtesy of Hugh Chesterman and play_station.

So it is good sense to begin with the work Counterpoint. This is our place of entry into the politics of labour; the artist’s practical insurrection.

In Counterpoint Rundle has reworked a diagram representing the classic market theory of wage determination. The theory is that the higher the wages, the more a person will be willing to work. But once the wages reach a certain point, the worker will not wish to work more because they are already earning a sufficient amount for what they do. On the contrary, the employer isn’t willing to pay too much for labour (as a cost of production). Thus wages will find a meeting point where the supply and demand are, supposedly, satisfied. Of course, there are myriad issues with this classical market theory of labour, but one is most pertinent. And that is, for the market to function in such a way, there must be restricted state intervention. If the market were to allocate the right wages, for example, nothing could inhibit the free and open supply of labour. Productivity is ensured when the market is in its most perilous condition. In other words, with the free-market as a means of allocation and distribution, difference is subsumed, inequities neglected, and humans relegated to mere numbers.

The disruption that Rundle poses to this is playful, something more significant than ostensibly appears. Where the demand curve indicates ‘equilibrium’, in the perfect area where demand and supply should be met, a treble clef symbol has been inserted. What this is demanding, or demonstrating, is a collapse of the hierarchy that usually encodes the discourse and praxis of mobilisation. For, as I alluded to above, people are excluded from the politics of their own oppression. Far from dogmatic Marxism, where there are only two viable subjects, the Proletariat and the Bourgeoisie, here each can be their own subject maker. And it is this play in the everyday, as opposed to the solemnity of conference halls, where access and imagination are foregrounded. That is, in play, or in difference, each can and must have the opportunity to be creating themselves for themselves.

Deborah Rundle, Employee of the Month, 2017. Image courtesy of Hugh Chesterman and play_station.

Situating the disruption in Counterpoint is the work Employee of the Month, a recreated staff car park with a placard on the wall reading ‘Reserved for Employee of the Month’. Coincidentally, the number of the parking space is 51, linking it to the 1951 Waterfront Strike, the biggest industrial strike in Aotearoa's history. The focus on industrial relations in Rundle’s artwork A State of Emergency III also runs through the whole exhibition. Employee of the Month elucidates not only the atomised individual, but also how they are constructed through antagonism and competition among one another. The work’s reference to 1951 is a visceral example: during the Waterfront Strike, workers were pitted against each other. Those who striked were blacklisted by the government. Those who worked were blacklisted by their friends. Relationships were destroyed. It was even made illegal to help the families and children of strikers. Employee of the Month illustrates how this antagonism between people is becoming ever more palpable.

Employee of the Month highlights not only how people are cut off from each other, but also how they are cut off from and out of their histories—a process that appears to a far greater degree in the biography of economic imperialism. Due to neoliberal policy, especially privatisation and de-unionisation, the same kinds of mobilisation that we saw in 1951 have been rendered seemingly unviable. Nevertheless, drawing this historical connection reminds us what was being fought for: time. In 1951 it was earning more value for time. Now we are attempting to reclaim some time from value. Time is money and work and leisure are becoming indistinguishable.2 At some workplaces, breaks are now given at the employer’s discretion. This portrayal of capitalist time reiterates productivity and profit as the ‘common senses’ driving the economy. Rundle is asking how much of the action and politics of ‘51 we can bring into the present. What can we draw on to produce new ‘good sense’ and new labour formations?

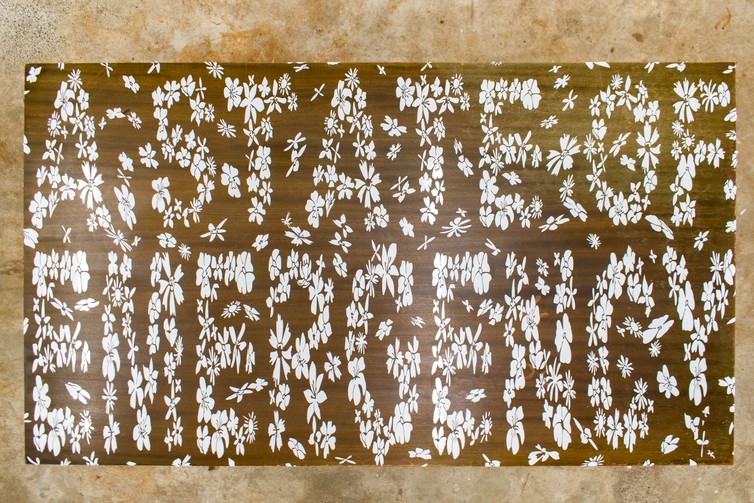

Deborah Rundle, A State of Emergency III, 2017. Image courtesy of Hugh Chesterman and play_station.

We turn finally to A State of Emergency III. Here, the artist is playing on the ‘casual Fridays’ theme-based joviality of the office. An old desk has been decorated with garish white vinyl flowers which, seen from above, form letters spelling ‘A State of Emergency’. Where Employee of the Month signifies atomisation and competition, this work addresses subject-representation. The agency and subjectivity of each person is confined to the limits of their small desks. What a person can be is restricted to what the business allows. We need to understand and empower diverse self-representation. But, as is continually emphasised throughout the exhibition, this is a contingent effect of changing discourse and power structures. It means challenging the systems that have produced oppressive common sense.

Within the title are two double meanings which underscore such a structural analysis of subjectivity. The first is ‘State’. One meaning is ‘state’ with a lower case ‘s’: a condition. Writers and theorists such as Arlie Hochschild3 and bell hooks4 have developed influential theories about an advanced capitalist condition. The other is ‘State’ with a capitalised 'S': the form of governance. Through this, we can read into the illegitimacy of power exercised through the nation-State. 'Emergency’ has one meaning as crisis, but another as coming into existence. And together we see a multiplicity of meanings and possibilities arise, epitomising the politics of DOWN TIME.

Rundle is bringing the relevance of 1951 into the present day. For, as common sense would decree, the union militancy of that era supposedly represented not the beginning or continuation, but the end of something. In addition, it is plausible that crisis gives rise to the possibilities of new things. Of course, this is not an argument similar to the Accelerationists or Posadists who rely on the godly claim that communism is an imminent evolution of capitalism.5 No, Capitalism flexes and bends. It does not break so easily. A State of Emergency III is recognition of how it did. And an exhortation of how it can be broken again.

About the artist

Principally utilising text, Deborah’s practice investigates the ways in which power plays out in the social and political domain in order to muse on possibilities for change. Refusing to draw utopianism to a close, she explores unrealised potential lying within everyday life and suggests a political imagination beyond ‘there is no alternative’. Her practice probes the contemporary world, often focusing on slippages within language in order to open up alternative meanings. Additionally, Deborah is a member of the art collective Public Share, which combines object making and site exploration with social engagement and critique, with a particular focus on workplace rituals.

-

1.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, ed. and trans. by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (London: Electric Book Company Ltd, 1999), 430.

-

2.

Benjamin Snyder, The Disrupted Workplace: Time and the Moral Order of Flexible Capitalism (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2016), 55-90.

-

3.

Arlie Hochschild, The Managed Heart (California: University of California Press, 2003) 3-23, 89-136.

-

4.

bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (Manhattan: Harper, 2000).

-

5.

Rosi Braidotti, “Thinking as a Nomadic Subject Lecture” (lecture, ICI Lecture Series ERRANS, ICI Berlin, Christinenstr, Berlin, October 7, 2014), https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/rosi-braidotti/.