Exhibition Essays

Enjoy Gallery Catalogue 2005

December 2005

-

Introduction

Jessica Reid -

Hunt

Michael Havell -

The Bomb

Sarah Miller -

Soliloquy

Amy Howden-Chapman -

Untitled (Pictures, Objects, Enjoy, Cuba St, Wellington, 2005)

Melanie Hogg -

Notes on Grand Narratives

Daniel du Bern, Simon Denny, Tahi Moore -

Ideas for banners for The End of Water

Jessica Reid -

HUMDRUM

Thomasin Sleigh -

Playing Favourites

Jessica Reid -

Everything I Know at the Top I Learned At The Bottom

Jessica Reid -

Michael Morley

Louise Menzies -

Soft Serve

Kate Wanwimolruk -

Repeat Performance 2005

Jessica Reid -

Schlock! Horror!

Jessica Reid -

Special At Enjoy. First Year Show

Jessica Reid -

Spellbound

Pippa Sanderson -

At Home (In Transit)

Jessica Reid

Soliloquy

Amy Howden-Chapman

Entering Sandra Schmidt's show titled Soliloquy, I was immediately drawn toward the central work,

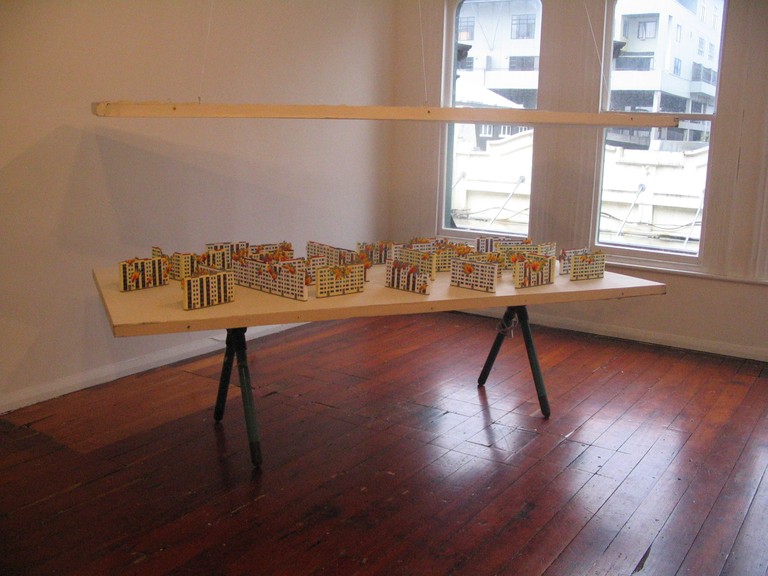

a reconstruction of an East German housing estate rendered from toy parts. This work feels like a soliloquy: constructed from memory, and seemingly levitating between two parallel white planes, the work seems to act like a story told in a single breath. It is only possible to negotiate the work from its borders, to look at it, circling it; it is not a conversation, it’s a single sustained description by the artist, a memory of a time and place.

The dominant nature of the central work is on closer inspection built up from thousands of tiny units. The housing blocks are constructed from tiny plastic beads melted together. Each individual bead is still identifiable and the blocks have the effect of pixelated three-dimensional sketches. The housing blocks stand independently, but are carefully arranged across the expanses of a white tabletop. The relation of the blocks to one another seems to have been transcribed from a map of a site. The blocks, all nearly identical in form, are placed at a similar distance from each other, and at certain angles give the sense of being arranged to most effectively balance space and community for the inhabitants, or to maximize sun.

However, the reconstruction of the blocks differs from an architectural model in a number of ways. The arrangement was constructed entirely from memory. With this in mind, it’s interesting to consider at which point accuracy was waived, and the model began to reflect the gallery space. Sandra can point to a window in one of the blocks: “This was my bedroom window” she says. It is exactly the same as all the other windows, but instantly that block seems to jump out, to have a special prominence, and I begin to consider the personal nature of the structure as well as its social narrative. How far away is it from the original?

With the knowledge that the work was created from memory, certain questions arise. What has been left out and why? There are no roads or model people, there is no sign of nature. All that we are shown is the form, the shells of the buildings. They are isolated for us and although they may first read like a miniaturised version of the real, they easily become fictional, independent of a real urban landscape. The buildings hover in their own place; they have no sense of relationship to the wider area, and any information that might relate their position to a real geographical area is absent. The only means we have of orientating this structure in the real world is through the personal narrative Sandra reveals around it.

This sense of an unsecured floating narrative is enhanced by the tight visual boundaries created by the two flat planes; one acting as a table surface on which the forms are placed, the other suspended parallel above the collection of buildings. In this way, the models do not appear directly in the physical space of the gallery but in a formal island. The planes act as a three-dimensional screen on which nostalgia is replayed; an arena of memory which we have been invited to observe. This separation from the 'real' acts as an interesting comparison between the buildings and apartment blocks seen outside the gallery window. The planes which the work hovers between could be seen as an island of East German ideology, suspended amongst a sea of New Zealand housing. National myths, the stories we are told about state housing and New Zealand’s continuing obsession with owning your own home, are held up for examination by this work, which manages to eloquently tell the story of a childhood behind the Iron Curtain. As Wellington becomes increasingly dense, low-cost apartment buildings sprouting at every corner, we begin to question who is in charge of monitoring the overall design of the city. The uniform suburb of Soliloquy raises timely issues. What are the ideal boundaries for suburbs and cities? In a world where sustainability is an increasingly important aspiration, and where a denser city uses less energy, do we have to balance uniform utilitarianism against American-style suburban sprawl?

The choice of tiny toy beads as the material for the construction of this structural memory gives the exhibition the feeling of a dystopian Legoland. There is also a sense of naïvety and the vast time it must have taken to construct may have become a time of nostalgia. It must have been a repetitive task of mass-production and yet Sandra gives the process an optimistic spin: “I like to free objects from being utilitarian, give them an increase in value.” So tasks of works become playful. The construction of the houses conjures up remembrance as she tries to get the same “value and dignity for cheap materials.” However there is a sharp intervention in the piece that acts to curtail the nostalgia trip, a device that also causes the viewer to second guess whether it is an accurate reproduction, a depiction of memory, or a story that is still being told. Flames in the same plastic bead arrangement break up the monotonous grids of the buildings’ windows. These small patches of colour burst out like explosions on some buildings and engulf several floors of others, giving the entire work a sinister air at first glance. Although the pixelated renderings vaguely recall to mind images of the Twin Towers or the carnage of kindergarten bombings, in this context the colours react against the monotony and formality of the buildings and seem like a visual burst of excitement. Fire is both a force of destruction, but also a source of heat and comfort. Sandra does not see fire as a retrospective day-dream fate of her childhood dwelling, but rather a way to introduce a natural element and visual variation into the otherwise stale forms. In context with Sandra’s other works, the burst of flame loses its malicious twist, and becomes part of the artist’s process of deleting and cutting down images. The fire, like cartoon blasts of red and yellow, gives welcome relief, the only sign of anything living, natural or organic in what would otherwise be a stylistic wasteland

Sandra talks of childhood living in the buildings as uniform but happy. Space was confined: her childhood room, two metres by four metres, was small enough you could reach out and touch the walls. “You knew that your room was identical to your neighbour’s room, that the rooms were filled with furniture identical to your neighbour’s furniture. It was a community of formica tables and yet”, emphasises Sandra “it was happy and warm. Everyone was united in the simple fact that they had a roof over their head.”

The second part of the exhibition moves away from the floating impersonal external space and into a small corner of the gallery doused with dated wallpaper, and decorated with scribbled-on magazine pages and a collection of images. One is the childhood face of Sandra grinning out at us from a black and white photo. Though there is a contrast between exterior and interior setting, the way spaces are constructed, transcribed and deleted is considered again. There is a map in which all the place names have been scribbled out, there are altered images from tourist brochures, upturned postcards, and images where the central object, an iceberg, has been overridden by permanent marker. It is possible to imagine that this corner is a reconstruction of Sandra’s small childhood room. Perhaps these images stuck to the wall are spaces of the future, vast lands to explore, lands where you could reach out your fingers and feel nothing but contours of the empty map reaching out infinitely in every direction.

There is a sense of continuity in the way space is dealt with. Space is not described, but played with. Things are remembered and understood through their re-rendering of form. All unimportant information is discarded under ink or through flames. Sandra’s Soliloquy tells stories of space that she has transformed, and we are invited to build our own memories within them, to consider if we are in hostile environments, or warmed by the way Sandra has given the materials around us a new life and significance.