Exhibition Essays

Latent Image

June 2016

Latent Room: A photographer’s response

Caroline McQuarrie

#photographytourism

In December 2015 I visited Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, UK. I paid my entry fee to the National Trust volunteers manning the gates and joined the stream of people being ushered through the historic building, room by room, until they reached the medieval hall where the giant Christmas tree had been erected and mince pies were being distributed. About halfway around this procession stood an unassuming window beneath a large leadlight latticed window with five tall, arched sections. Most people simply walked past it; this however was my destination.

Caroline McQuarrie, #photographytourism, 2015, screenshot, accessed 14 July 2016, https://www.instagram.com/p/_z1qg_BPBX/?taken-by=caroline_mcquarrie

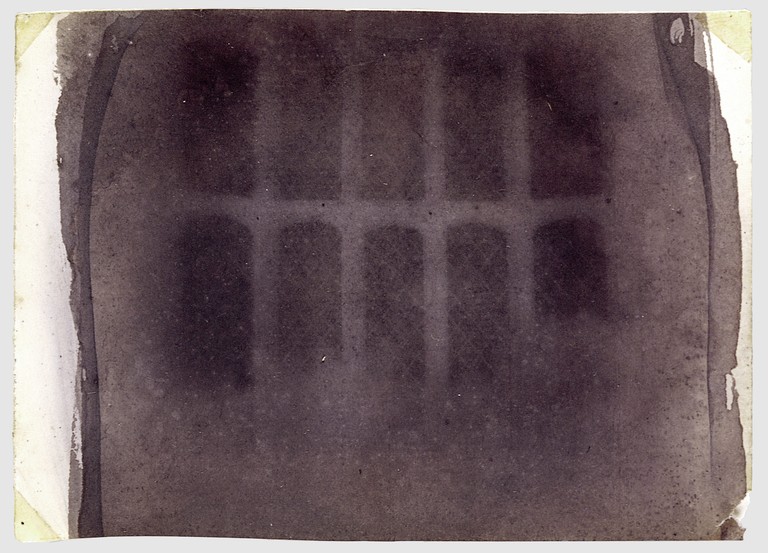

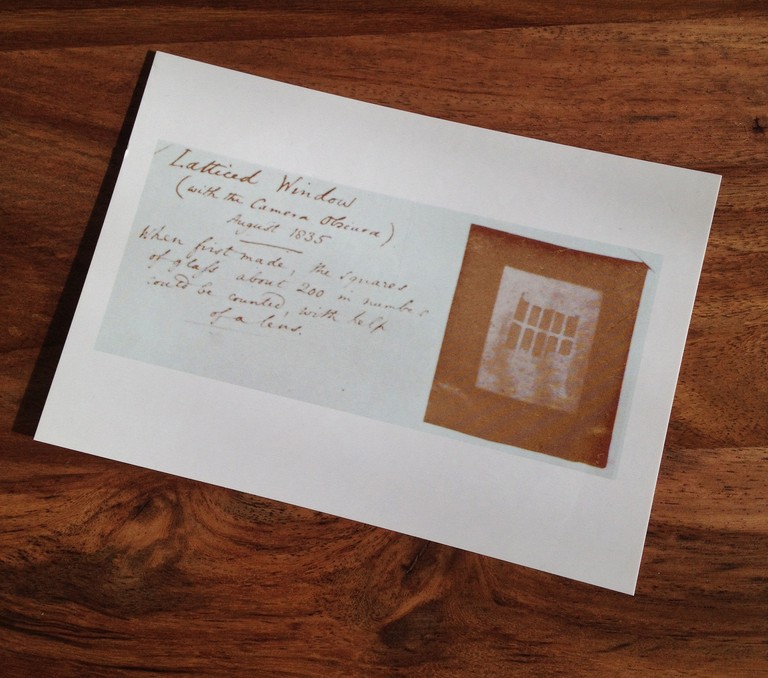

In August 1835 William Henry Fox Talbot made what may have been his first successful negative of this window. He had been working on perfecting the photographic process for some time, placing his small wooden box cameras at various sites around the house causing his wife to nickname them ‘mousetraps’. The negative shows the light from the latticed windows burned into the small piece of light sensitised paper he had placed into the ‘mousetrap’ camera. The light from outside the window was bright enough to darken the silver halide particles where it hit the sensitised paper. In this view of Fox Talbot’s world, the bright windows are dark latticed shadows and the surrounding interior room is closer to white.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Oriel Window, South Gallery, Lacock Abbey, probably 1835, photogenic drawing negative, 8.5 × 11.6 cm (3 3/8 × 4 9/16 in.), irregularly trimmed, Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee and Anonymous Gifts, 1997.

While Fox Talbot wasn’t the first person to make photographic images, he was one of the first to make those images permanent. Most importantly he invented the negative enabling photographs to be reproduced,1 but his discoveries were only one step in the continuing evolution of the photographic image.2 Latent Image both utilises and extends many of the early stages in that evolution; it is a work that encompasses the photographic. This is a surprising statement to make about an exhibition that doesn’t include a single photographic image.

The Fossilised Room

When you enter Enjoy Gallery a monolith confronts you. It takes a moment for your eyes to register what you are seeing; a large black box, but not a perfect rectangle. As your eyes begin to adjust you notice it has texture, one side even sparkles. You observe shapes within the form, focusing until they become a door, a coat hanger, windows, grates and power points. It is topped with a lid that isn’t a lid, warm and wooden. Tiny details show joins and nails; it becomes a floor, a stage in miniature. With close attention, you start to notice that the monolith echoes the room you are standing in. The windows, the doors, the grates and sockets, the lead lining in the corner of the floor are all there, upside down and in miniature.

Caitlin Devoy’s Latent Image is a 1/4th scale model of Enjoy Gallery turned upside down and inside out, then placed on its head within the gallery space. The artist has burnt the whole surface of the work black, except for the floor, which is immaculately rendered in warm wood. What we are confronted with is a negative of the space we are standing in, concentrated in perfect miniature. The crafting skills are astounding—it is possible to spend an inordinate amount of time just drinking in the details. But while this work has an extraordinary physical embodiment, that is not its only magic.

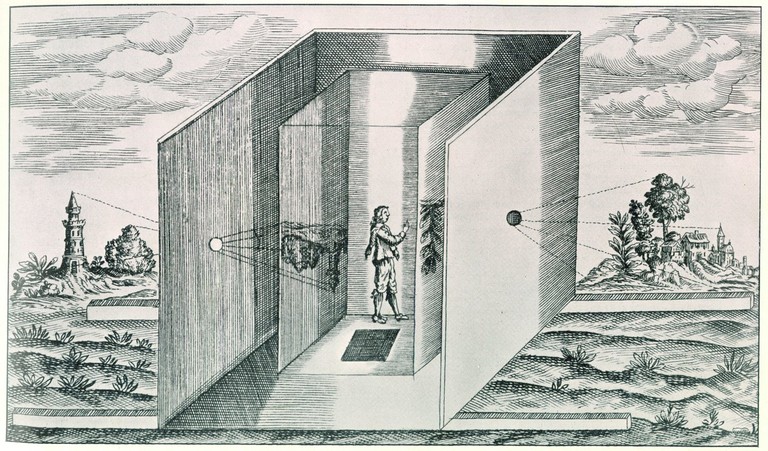

More photographic than a photograph

The story of photography has two strands: the development of the camera and the invention of the light-sensitive print. The story of the camera begins with the camera obscura, simply a darkened room with a small aperture that lets light in. Light is then reflected off whatever is outside the room through the aperture onto the wall opposite. Because light travels in a straight line, objects on the ground are reflected high into the room while objects up high are reflected low in the room. In effect, the outside world is projected upside down and back to front into the inside of the room. It often surprises people to learn that this simple concept is still in effect in every camera. As light enters a lens the rays cross over each other and form an upside-down image of the world. Cameras are designed to flip the image so that we can distinguish it more easily.

Athanasius Kircher, “Sketch of Athanasius Kircher's portable camera obscura”, 1671, from Ars Magna Lucis, Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, accessed 14 July 2016, http://camera-obscura.co.uk/camera_obscura/camera_history.asp

This explains the inversion of the fabricated room in Latent Image—we are looking at the model of the gallery as though we are inside the camera itself. The gallery has been turned into a camera obscura but the image has been made solid—extremely solid. This ‘photographic’ image is possibly the heaviest ever made. However, Latent Image is not quite so orthodox. If we imagine the gallery itself is the camera obscura then the image is being projected inward from the interior walls of the camera, or perhaps the image is projecting itself outward onto the room it inhabits. So this is another inversion, rather than the outside world being projected inwards, the camera and the image become a chamber that only reference themselves.

The camera obscura phenomenon was observed by different cultures at different points in history.3 It was largely used as a scientific tool until the Renaissance when it was employed as a device by artists to draw perspective correctly. Shrinking the room to the size of a box and adding a lens in the late 1500s sharpened and brightened the image. By the 19th c. the camera lucida had been developed, a box-free portable device patented in 1807. With the use of a prism the scene being observed and the drawing paper overlap in the viewer’s vision, allowing even an amateur artist to produce passable drawings. This is exactly what William Henry Fox Talbot attempted to do while on his honeymoon in Italy in 1833. However, he was so disappointed with his drawing efforts that he determined to find a better way to fix the views before him. Fox Talbot remembered a small box camera obscura he had also attempted to draw with years before and wondered if there was another way to capture the image it projected. Thus began his journey towards his first successful negative at Lacock Abbey just two years later.4

The Salted Shadow

When you move around ‘Latent Image’ and the light shifts, you notice that the surface on the window side sparkles. You wonder if this is a condition of the burnt wood, or perhaps a trick of your eyes? But it is neither, it is salt. The artist has sprayed the surface of the charred wood with a salt solution and it twinkles in the light.

The mechanics of the camera are only half the story, for Fox Talbot’s main discovery/invention was the ability to fix the captured image. It was in this final piece of the puzzle that modern photography was born. Others had previously made what we now think of as photograms by placing objects on light-sensitive surfaces, which when exposed to light created images where the object’s shadow had fallen. Thomas Wedgwood, son of the potter Josiah, made great strides with a process using silver salts in the 1790s but was unable to ‘fix’ the images. They only lasted a short time before continued exposure to light rendered them completely black. Wedgwood’s experiments were widely published and were certainly part of the body of knowledge Fox Talbot used in his own work. In France, Nicéphore Niépce was making progress in the invention of a process that after his death in 1833 Louis Daguerre would develop into the daguerreotype.5 However the daguerreotype was a direct positive image on a metal plate that could not be reproduced.

Fox Talbot’s work first gave us a negative ‘salted print’, like the window image. Eventually, he developed this into a thinner paper negative process called the calotype. When a calotype negative was placed face down onto his original sensitised paper and left out in the sun, the result was a positive print, a salted print. This ‘printing out’ process could be repeated many times, making the first truly reproducible photographs. This process eventually lead to the glass plate negative collodion process, which later still developed into the film-based processes that would dominate photography for the next century.

The Latent Image

Have you ever looked at a darkroom photographic print before it has been developed? There’s nothing there. You put it under the enlarger, you shine light through your negative directly onto the paper and seemingly nothing happens. But then you walk across the darkroom, dip the paper into a tray of developer, and in a matter of seconds the positive image starts to appear before your eyes. But the developer doesn’t make the image, the image was there before the developer was applied. So where was your image?

We call this a latent image. The light from the enlarger (or in the case of film, from the sun) has caused a chemical reaction in the silver that is not yet visible to the eye. It only changes from latent to visible with the application of developer, causing the silver exposed to the light to turn black. But as Thomas Wedgwood found out even this is not enough. Another stage is needed, the image must be ‘fixed’ before it can be exposed to more light. So we also bathe our print in fixer, washing away the unexposed silver so it can no longer darken in the sun. One common type of fixer is sodium thiosulfate—once again, our old friend salt. In Latent Image the artist has ‘fixed’ the blackness in her work with a salt solution which sparkles on its surface where the light falls through the windows of the gallery.

In some ways, Latent Image is the opposite of an actual latent image. It is not invisible. It is in reality very hard to ignore, placed into the gallery like the Kaaba Stone at Mecca or the monolith from the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey (if it had been created by aliens who were very meticulous craftspeople—craftsaliens?). But it is latent in that it feels dormant. Like the 2001 monolith, it feels as though it is waiting for someone to come and activate it. We also have an idea that images are two-dimensional, flat. But a model can be an image of something, just as a mask is an image of someone’s face—it is the mimicry of an existing object that makes it an image. And so Latent Image is a funny sort of photographic image, and like so many photographs it is ambiguous. It turns the gaze of the gallery in on itself while simultaneously opening our attention outward, back in time to the earliest experiments in optics and photography.

Afterimage

We often speak of an image being burned into our retinas or our brains. We have all played with the phenomenon of the ‘afterimage’ where we look at something bright and then close our eyes to see the negative image still there on the inside of our eyelids. The burnt surface of Latent Image is a physical afterimage, burned into the world to make it visible in a way the room it echoes is not. We take rooms for granted, they exist and we exist in them. We might think of the colour of the walls or how the furniture will fit, but mostly we take them for granted. The salted, blackened wood in this work has so many echoes for me; it is charred driftwood washed up on the beach after a storm, it is a log left in a fire as it dies away, it is the remains of a house after it has burned (so then, not so permanent). It is the work of photographer Chris McCaw whose film exposures are pointed directly at the sun for so long the light literally burns a path through his negatives.6

The photographic associations are not just historical ones. I am reminded of photographers who have attempted to photograph voids despite this being a medium which is peculiarly unsuited to capturing darkness.7 How do you take a photograph of nothing? If there is no light to expose the film then there is no image, but if there is no light then your film has captured the image, an image of nothing. In a negative, the shadow becomes the highlight. In Fox Talbot’s first negative the room’s interior darkness caused almost no chemical reaction on the paper, staying white. Like an afterimage his latticed windows show an external void, burned as darkly into the paper as they are burned into the history of photography.

Caroline McQuarrie, Oriel Window postcard, 2015, Lacock Abbey, National Trust UK.

The Handmade

The crafting of Latent Image is astounding. When you are standing in front of the artwork it confronts you with its making. The tiny details describe the eccentricities of the room wonderfully and there is genuine delight in closely examining every nook and cranny of the artwork. The artist has shown her hand here, it is all over the piece; and then she has simply burned it away. It seems extraordinary that someone would spend so much time creating such intricate detail to then deliberately destroy it.

Photography is often thought of as a mechanical process. It is a common belief that to take a good photo you just need a good camera. But as anyone who has applied themselves to photography knows it takes a little more than simply pressing the shutter, and in the early days of the medium this was particularly true. Early photographic practitioners were meticulous in their crafting of both the composition of their images and the making of the print. Early processes such as calotypes, daguerreotypes and tintypes required a great deal of skill to execute. The daguerreotype was such a complex (and dangerous) process it could really only be done inside the photographic studio.8 The much cheaper tintype was more versatile and could be prepared and developed in a smaller space.9 Photographers’ wagons travelled across settler America making portraits processed in portable darkrooms; large boxes on wheels which were miniature echoes of more substantial darkrooms, just as Latent Image is a miniature of Enjoy.

A photographic image is made, particularly one that we hold in our hands. These days it might be made by a digital printer, but every element that produced that print was designed and built by a person. We imagine mechanisation and digitisation is somehow automated because we didn’t personally have a hand in its construction, but we forget that cameras and computers didn’t spring from nowhere. They are simply tools like any other, made by people. Photography is a cultural construction, it was invented and subsequently gained huge popularity because for some reason we seem to need it.10 It is easy to forget that amongst the proliferation of cameras and manipulation software there are simply people making images as there have been for 180 years. Latent Image again echoes its photographic referent; crafted by the human hand.

The Contortionist

There is one final piece to this delicious blackened puzzle; the Enjoy gallery space was once a photography studio. William Berry ran Berry & Co. in the space from the 1890’s through until about 1930.11 The size and shape of the gallery space are exactly what we would expect a photographic studio of the time to be, the most striking aspect being the large wall of windows which provided the light. Prior to artificial light sources being available (or reliable) the best way to run a studio was to have large, south-facing windows with a versatile set of blinds allowing you to control the light falling on your subject. Too little light and an exposure wouldn’t be possible, too much and the harsh light would be unflattering.

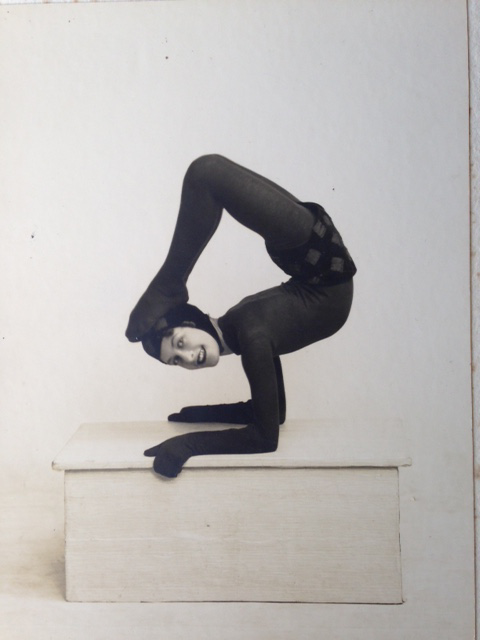

In Latent Image the gallery windows are rendered in sheets of lead. Breaking from the burned wood of the walls and fixtures, these lead plates are reminiscent of slates, or of the plates used to shield body parts during an x-ray. They are dark like Fox Talbot’s windows. They are the ultimate blocker, letting nothing through, the opposite of the glass in the actual windows. Yet they also have a softness, they are the silky grey of graphite, and I feel that if I run my fingernail down one it would mark too easily. This combination of tough and soft is echoed in a photograph the artist showed me after her artist talk at the gallery. Taken in the 1930’s, it shows a woman (the artist’s great-aunt Isabel) on a low, wide white plinth in a photographer’s studio. The background is white and the plinth is white, but dirty (as plinths become in photographic studios), disrupting the illusion of a continuous white background. The woman is wearing black from her hood all the way down to the bottom of her tights and her mittened hands. But again the skill of the photographer shows up the flaws in the illusion, rendering the different shades of black evident. She is a physically slight woman (like the artist) and she is propped up on her arms, contorting her body into a circle on top of the plinth all the while turning her head towards the camera and smiling benignly at it. She wears small black diamond-patterned shorts and hood and the effect of the whole is a black ‘o’ shaped person against a white background.

Great Aunt Isabel

I asked the artist where and when the photograph was taken and she tells me Whanganui, and estimates pre-WWII—just a little later than Berry & Co. but roughly contemporary to how they would have operated. I am captivated by this small lively woman so clearly enjoying what she is doing. The artist showed me this photograph because I was amazed that she was able to perform a feat of contortion herself, a skill that clearly runs in the family. Latent Image was assembled inside the gallery, with the walls and floor joined together by the artist from the inside. When it was complete and the roof had been placed on top, to leave the interior the artist had to contort herself through a tiny portal on the underside of the structure. I cannot even see this portal let alone imagine how a grown person could manoeuvre themselves through it. Yet somehow this seemingly unconnected photograph brings the whole thing together. This young woman is a small black void inside a white photography studio, roughly contemporary to the studio the artist has recreated. Every element of this work and even the artist’s family history adds another layer to the story the object is telling. Latent Image is a work that has so many echoes they start to bounce off each other and become amplified, adding and multiplying until they are a cacophony of layers of meaning.

The Latent Room

It could be said that every room is latent until a person walks into it, that a room not in use isn’t really a room at all. Photography studios and art galleries are perhaps the most latent of rooms, designed to be void until they are filled with a person’s creative endeavours, unable to function the way they are intended until we activate them. They are non-traditional voids; white rather than black, blinding with their emptiness until somebody fills them. Latent Image, like Talbot’s negative, makes the brilliant white deepest black. It turns all our expectations upside down and inside out, playing with architecture and photography, with scale and materials. It lays bare the latency of the art gallery and becomes the physical embodiment of a photographic negative, burned into our retinas as the artist burned her intentions into the surface of the work.

Note: I am indebted to the artist, Caitlin Devoy, not only for making the work but also for her fascinating artist talk that helped me pull many of my own thoughts about the work together. Between the dots she connected and the ones in my own response to the work this piece of writing came together. I would also like to thank Deidra Sullivan for sharing her extensive knowledge of the history of photography.

-

1.

As opposed to the singular daguerreotype, developed simultaneously in France.

-

2.

For a more thorough and nuanced discussion of the conception of photography see: Geoffrey Batchen, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999).

-

3.

The camera obscura phenomenon is mentioned by the Chinese philosopher Mozi (470 to 390 BC), who recognsed that the light was travelling in straight lines, therefore inverting the image. Aristotle (384 to 322 BC), was familiar with the concept, and Euclid's Optics (c. 300 BC) mentions the phenomenon as a proof that light travels in straight lines.

-

4.

Malcolm Daniel, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) and the Invention of Photography, accessed July 14, 2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tlbt/hd_tlbt.htm

-

5.

Niépce’s most successful invention was the Heliotype process, which used a light sensitive plate that an image on paper could then be laid over and printed through (like a negative), creating an etched plate which could then be printed from with ink like an etching. This process added more to the technology of the printing plate than photography as we came to know it through the negative/positive process. However, Niépce’s acheivements were extraordinary and it is gratifying to see him being recognised as a key figure in the development of photography.

-

6.

“Sunburn”, Chris McCaw, accessed July 14, 2016, http://www.chrismccaw.com/SUNBURN/SUNBURN.html

-

7.

My own photographs of mine shafts in the Enjoy Gallery exhibition Homewardbounder (April 1 – 25, 2015) attempted this. I am also reminded of Mizuho Nishioka’s haunting night photography in this must be the place: three photographers at the City Gallery in 2012. We both shot our images on film and deliberately utilised our understanding of exposure to create a velvety black void in parts of our images.

-

8.

This is why we only see portrait daguerreotypes.

-

9.

The tintype was a form of the wet plate/ collodion process invented in 1851 by Frederick Scott-Archer.

-

10.

For a more comprehensive discussion of this idea see: Geoffrey Batchen, “Ectoplasm” in Over Exposed: Essays on Contemporary Photography, Ed. Carol Squires (New York: The New Press, 1999), 9-23.

-

11.

Quite famously in the 1980’s nearly 4000 glass plate negatives were found stored in the building and gifted to Te Papa, who in 2014 spent some time trying to identify 190 WWI soldiers who had their photographs taken before they left for the war.

See: “The Berry Boys – photos featuring New Zealand World War One Soldiers”, Lynette Townsend, accessed July 14, 2016, http://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2012/06/20/the-berry-boys-photos-featuring-new-zealand-world-war-one-soldiers-2/