Exhibition Essays

New Work Series. 1

December 2004

-

Liberated by newness

Jessica Reid -

Hullbreach

Jessica Reid -

The story of three sentences

Rita Langley -

Golden Axe: Interview by Jessica Reid

Jessica Reid -

Enjoy Performance Week

Marnie Slater -

In association with Wellington Architecture Week...

Katie Duke -

Drawn

Jessica Reid -

No need to be afraid

Jessica Reid -

You better watch out...

Jessica Reid

Hullbreach

Jessica Reid

Every so often we are told that painting is experiencing either a crisis or a resurgence. Most recently, and particularly during last year's Whitney Biennial, there was debate about the renewed interest in painting, especially figurative painting. For the committed painter it's all very confusing. In July 2004, Enjoy, in a rare move, had a show of painting, when it exhibited the works of Miranda Parkes. Besides the works themselves of interest was the artist's willingness, in her artist's talk, to address the conceptual difficulties which painters face today. Parkes admitted that many painters struggle with questions of how, and even why, they should paint in this day and age. Well, the resulting works are a vibrant celebration of painting and vindicate her decision to work in that medium.

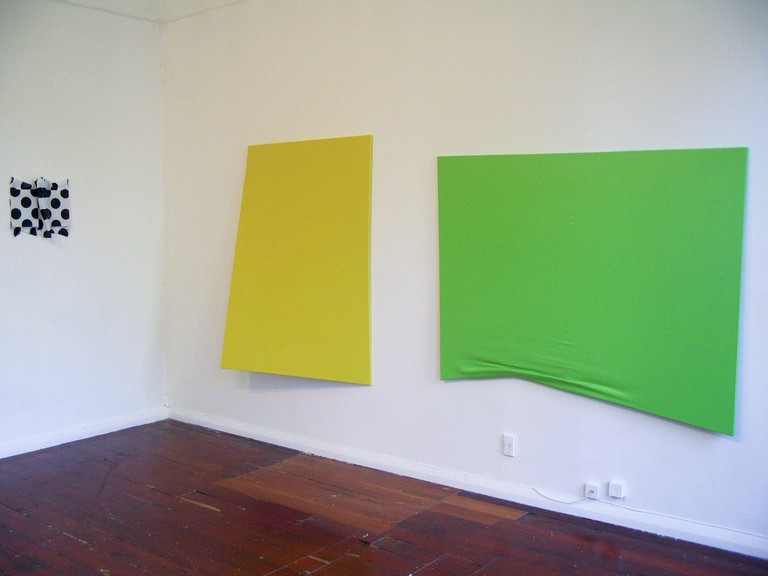

A recurring theme in World War II naval movies, I am told, is when a ship has been torpedoed. The hull of the boat bursts. Sailors run around yelling 'hull breach'. Ripped metal, sea water gushing, sirens screaming, rivets popping. But in Miranda Parkes' exhibition despite the paintings' 'leakages' off their two-dimensional surface, Hullbreach appears to have been made with a more considered hand and critical eye than the chaos the title would imply. Although all works are wall-based, none lie flat against the wall. They are playful experiments with the traditional basics of the medium. Frame-making, canvas-stretching and ground-painting are all processes employed but instead of being ‘art that conceals art’ they are blatantly brought to our attention and shown as interesting in themselves. One untitled work seems to be, almost comically, struggling to maintain its wall attachment. Rather than spewing forth, it pathetically clings to the wall, but is so weighed down by its baroque folds that it can hardly hold on.

The real explosion, that causes the hull breach comes from the colours. Sizzling and vibrant; lime green and orange stripes form one work painted on acetate. Being painted from the underside, the plastic has the smooth, shiny surface finish of a glistening wet shower curtain, catching the sun's rays in the morning.

Parkes recalled in her talk how she was influenced by the sculptor and installation artist Jessica Stockholder, and how both shared an interest in the blur between painting, installation and sculpture. Her confident use of bright colour is her most obvious debt to Stockholder. What a startling rarity it is to see such uninhibited use of colour, in anything, but particularly in painting. More cautious artists might fear that gushing colour will swamp anything else present in a work. They might dread the accusation of being frivolous and childish and that the viewer won't be able to see anything beyond this. Yet in Parkes's work, her use of colour actually 'brings out' and emphasises the forms and materials she employs.

Parkes' paintings pay all the attention to form and detail as the careful nips, tucks and folds in a seamstress's handiwork. The surfaces are bunched-up like pleats in a skirt. 'Black cross' is made of hat fabric, a stiffer material then canvas, but also used, I'm sure, for the material's references to dress. The fabric has been sculpted to curve and fold in arcs coming out of the wall. It is painted in glossy black, almost lacquer-like, paint, but pin-stripes of colour below peak through the surface. It is made from two separable parts which twisted over each other forms the cross- though perhaps not immediately apparent, a reference to Malevich's painting (1916-17) of the same name.

Other visual allusions to clothing and their wearers abound. Gathers in a large green canvas's surface suggest an ankle provocatively poking out from underneath a skirt. A plastic bag adhered to a board is of black polka dots on white in the style of eighties fashion-revival ra-ra skirts. A vinyl work, in a colour best described as a 'tarty-pink', looks like the miniskirt of an amply-bodied woman, stretched to breaking point across her voluptuous thighs. The folds and creases suggest the material bunching as the woman struggles to walk in her restrictive garment. Or maybe the work suggests the folds of sagging pantyhose. Whatever the garment suggested here, the size of the painting gives it a human, bodily-scale.

The most successful part of Hullbreach is its installation, which creates something much greater than its parts. Evenly paced in its hanging, the viewer finds interest in every work. Miranda Parkes brought to the gallery many more works than could be shown. Over the days prior to the show opening, she experimented and interacted with the space with various combinations. The thought and effort she put into the show's hanging is clearly evident. Indeed the bold arrangement of the works gave everything else an ambiance. One viewer remarked how any object placed in the room; a coat or handbag left in the corner, was imbued with an art object aura. Hullbreach demonstrates that with careful consideration to methods and materials, painting need not be in any crisis.