Exhibition Essays

Offspring of rain

September 2019

Pearly dewdrops drop

Charlotte Forrester

The last time I drove along the Desert Road it snowed.1 It’d been raining all day. The road was slick with it. Then the sky darkened and the translucent drops of rain turned white, crystallising as the temperature fell. It had been years since I’d seen snow. It collected on the windshield, cocooning the car as I continued to drive along the highway, and a silence descended.

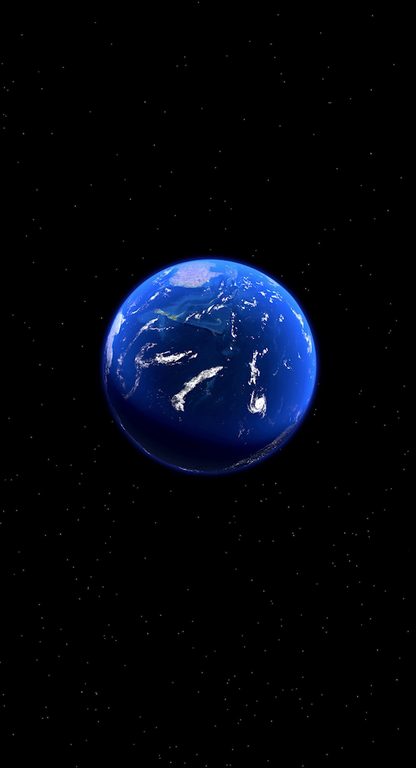

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, still, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

“Each thing … as far as it can by its own power, strives to persevere in its own being … Even a falling stone is endeavoring, as far as in it lies, to continue its motion."2 To watch snow fall is to watch water persevere in its own being. Too heavy for the clouds, it falls back down to Earth.

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, still, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

Water is, by nature, restless. It exists in a never-ending state of motion. Always evaporating, always condensing, always precipitating; its particles drawn close together then flung wide apart. So too is water always flowing through the human body, pulsing with every heartbeat, coursing up and down from head to toe, until we weep and piss and sweat it out. And in this restlessness, water is ubiquitous. “To say water is integral to life understates the case. We should properly think of our cells — and of those of every living thing on Earth — as bubbles of water … Life, its processes and structures, occur in its solution. Every living thing, then, is … a different inflection of water."3

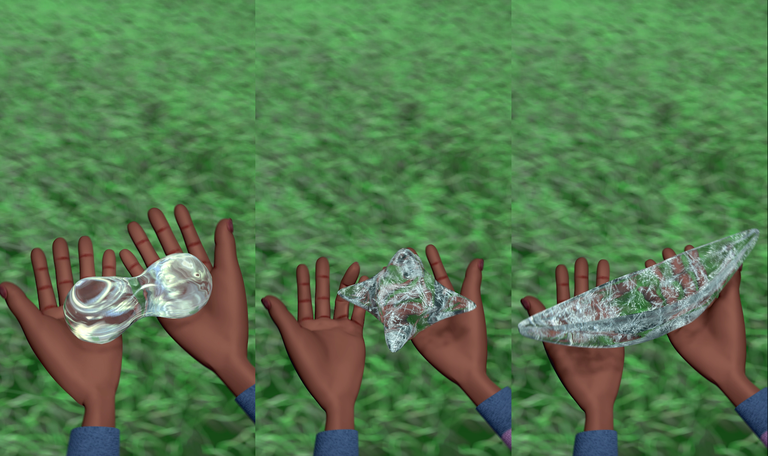

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, stills, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

To consider water is to consider the chaos on which existence rests: the birth of the universe and the spinning of our solar system; a thousand years of collisions. To consider water is to consider life in all its multitudes of inflection: from oceans to single cells to human beings. It is to traverse time on an impossible scale.

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, stills, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

Existing at this particular moment in time means existing in a state wherein the perseverance of life as we know it is being challenged. I dream of water gushing into my house, flooding room after room until it seems the whole world is submerged.

What does it mean to no longer believe we’ll live forever? The illusion broken, we stand face-to-face with our own impermanence.

And yet the word apocalypse does not find its etymology in roots relating to the end of the world. Rather, its Greek origins — ‘apo’ or ‘un’ and ‘koluptin’ or ‘cover’ — are placed side by side to mean ‘uncover’.

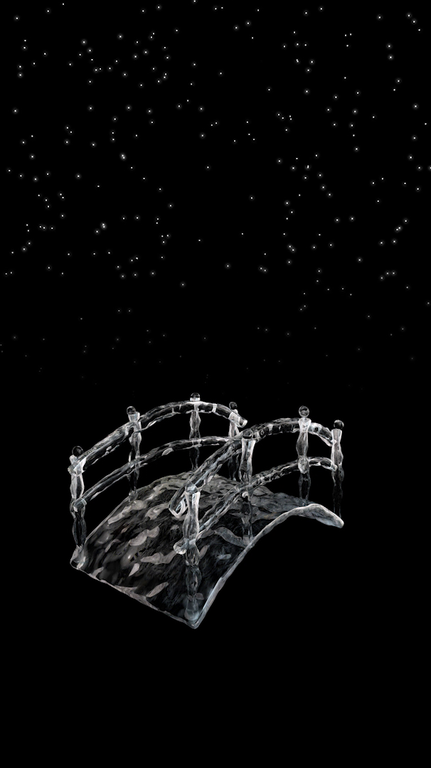

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, stills, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mountains and red dirt lay beyond my car window, as if the history of the world stood still while everything else just kept rushing forward. Driving through the snow, I was reduced to insignificance, some blip on the surface of the earth. Then again, I was something much bigger than myself: I was a part of something else.

Perhaps to uncover, then, is to “be surprised by what we see.”4 It is to marvel at the way things exist, as both “utterly unmysterious and unspeakably miraculous.”5 To witness the human body as transcorporeal, “always intermeshed with the more-than-human world.”6 To recognise ourselves as one inflection amongst an infinitude, each a different mutation, each an offspring of rain.

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, still, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

That silence was deafening as I drove along the Desert Road. I turned the headlights on high and watched the beams illuminate the pearly drops of snow. To watch snow fall is to enact an unequivocal presence, to conjure up a vital materiality.7 I watched it fall, and in this watching, I persevered. Then just like that, the snow stopped and the rain cleared and the highway left the terrain of the Desert Road behind, merging with some long country road and its gas stations and fast-food chains and vacant motels.

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of rain, 2019, digital video, still, 10:00. Image courtesy of the artist.

-

1.

The title of this text is taken from Cocteau Twins’ song “Pearly Dewdrops’ Drops.”

-

2.

Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 2.

-

3.

Alok Jha, The Water Book (London: Headline Publishing Group, 2016), 95.

-

4.

Bennet, Vibrant Matter, 5.

-

5.

Timothy Morton, “Guest Column: Queer Ecology,” PMLA 125, no. 2: 277.

-

6.

Stacey, Alaimo, “Porous Bodies and Trans-Corporeality,” Larval Subjects, 24 May, 2014, accessed 12 December, 2019, https://larvalsubjects.wordpress.com/2012/05/24/stacy-alaimo-porous-bodies-and-trans-corporeality/.

-

7.

Bennet, Vibrant Matter, vii.