Exhibition Essays

Our house (white indices)

November 2008

Outside of the Box

Hana Miller

The logic of sculpture, it would seem, is inseparable from the logic of the monument. By virtue of this logic a sculpture is a commemorative representation. It sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place.

(Rosalind Krauss, Sculpture in the expanded field, 1979)

Trenton Garratt used Enjoy Public Art Gallery as a workspace for the three days preceding the opening of his 2008 exhibition Our house (white indices). It was the first time he had chosen to exhibit in three years. He was still floating in the after effects of seeing a Louise Bourgeois retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum and was in the midst of final deadlines for his MFA at Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts. Autobiographically, the occasion marked a vanishing point between his past and present works.

In creating the show, the title of the installation came first. ‘Our house’ was a nickname Garratt had given to recurring themes of intimacy and domesticity that were surfacing in his studio practice.

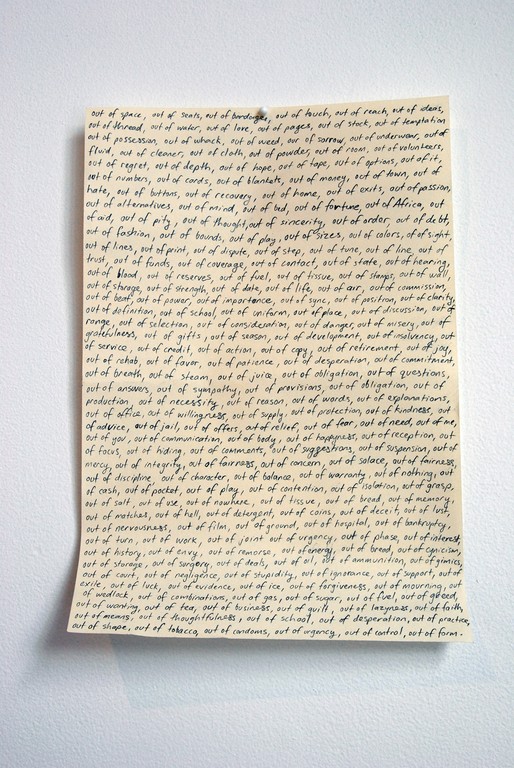

The end result was an installation that questioned the relationships between the various elements of the work: a labelled box out of which white clay pieces appeared to be spilling, a tall pile of very differently shaped white clay pieces positioned across from it, the dust covering the floor, and a stack of paper list- ing handwritten sentences beginning with ‘out of ’ and ending with anything from ‘space’ to ‘remorse’ to ‘tobacco’. Both the complete scene and its individual components gave the sense of aftermath, where both residue and conclusion inhabited the same space and shared a common hue. But what this aftermath said about its origins was—as the saying goes—in the eye of the beholder.

The connotations, or the ‘dot dot dot’—the indices—were all there. They were apparently falling out of the box labelled ‘Tapes Second Bedroom’, the box that made you think of moving house and organising your belongings into packages assigned with labels indicating what is inside and its next destination. Or of how this process might make you think of the objects, memorabilia, clutter that one accumulates over time in the personal space that we know as home. Perhaps you noticed how the sight of all that dust ties gestures to thoughts of accumulation and the passing of time.

This evocation of someone’s personal belongings and thoughts by way of words on paper brought a sense of intimacy that was as elusive as the various sculpted forms were unidentifiable, yet it was as palpable as the feeling of seclusion inside the gallery’s small space.

‘In some sense I wanted to slightly clutter the space,’ says Garratt, ‘but not bombard it. I was interested in the idea of the way you can clean a space without disposing of anything—sweeping stuff to the side, into piles, into boxes—so that there is evidence of there having been a mess but it’s been arranged a little to lessen the impact.’

This phenomenon sweeps across the spectrum of how we live in both our physical and mental spaces. It spans the quotidian and the universal. It is as fundamental as the law of physics, the terms with which we describe the nature of the world: energy can neither be created nor destroyed; it can only change its form.

The white particles of Garratt’s installation come in various forms, their presence can be seen in varying degrees all over the gallery, down to the sheer layer of white dust that covers the floor and gathers along the walls. It has been deliberately pushed around, kneaded into shape, organised into piles and containers so that it speaks, as Krauss suggests, ‘in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place.’

In this instance, ‘that place’ occurs in multiples. There is the gallery and there is Our house. From there the sense of place branches out further: there is the gallery both as a physical building and as its place in the life of the artist, of artists in general and of its various visitors. How does the gallery work as a platform for exploring the golden ratios of mess/impact? Where does art sit between mess and form?

Then there is our house and its relation to the box, the box that speaks of private spaces such as bedrooms and personal habits like tape collections, but also of storage and hoarding and the illusion of disposal and order. In the context of this work, the same box holds clay pieces in repeating forms, recalling the kinds of collections you might find in anyone’s room, from seashells to stamps. Fingerprints in the clay remind us that each of these pieces was made by hand, as were those in the more architectural pile across from it, sug- gesting an activity that could conceivably be as tedious and obsessive as collecting for the sake of collection.

Through both form and language, the box gestures to the box-like spaces that we call our homes, those places of shelter in which we undertake our daily routines, the nests we make with the bits and pieces we accumulate. Our house is a place where the deliberate coincides with the residual, where they face off in the architectural form of box versus pile; stored versus cast aside.