Exhibition Essays

Purpose-built

August 2018

Athenaeum Shrugged

Lachlan Taylor

Don’t tell me. You’re here for a special book.

Christopher Lloyd says these words to Macaulay Culkin in the opening scenes of The Pagemaster (1994), a little-remembered film about the animated denizens of a public library that sits somewhere between Beauty and the Beast (1991) and National Treasure (2004). You could not make The Pagemaster today. It wouldn’t land with contemporary audiences because our relationship to libraries, and especially to librarians, has radically shifted since an animated Culkin read his way out of a dragon’s stomach in 1994.

Libraries, and the information specialists that work in them, are no longer gatekeepers of centralised depositories of knowledge. In the film, Lloyd played both the eponymous Pagemaster—omniscient spiritual guardian of the library—and the secular public librarian. One is a hyperbolic allegory of the other, emphasising attributes of guardianship and care. But that figure no longer really exists in our cultural imaginations. The library has been a victim of the internet’s success as much as the town square or local retailer, and now the knowledge that specialists once guarded is as readily accessible as it is widely dispersed.

This feels like it should be a net good, and in part it is, but libraries are closing. Not public, general-purpose libraries, which will likely always retain a physical—albeit diminished—presence in civic life. The libraries that are suffering are specialist collections, those attached to institutions, corporations, and not-for-profit organisations.1 And they are closing everywhere. Some are absorbed into larger collections, some digitised, some are simply lost. The scholarship on what happens to these many collections after closure is frighteningly scant.2 Invariably, closures come as a result of cost-cutting, with specialist libraries seen as machine age baggage, weighing down institutions’ march into a digital world. We use these physical spaces and objects less and less in the internet age, but where should all this knowledge go?

The University of Auckland’s decision to shut down its specialist Architecture and Planning, Music and Dance and Fine Arts libraries has been the most high-profile and vociferously contested example of these closures in Aotearoa. The University, citing the burdensome costs of refurbishing the collections’ housing, intends to amalgamate the specialty libraries with its general collection. I found myself at a family dinner around the time of this announcement, my arguments for the retention of the existing space floundering against the unassailable bulwark of a single repeated refrain: “but everything’s going to be online soon anyway.” The notion that digitisation could be the saviour of specialist libraries carries a sharp irony, as the technological disruptions of the internet are a primary factor in library closures. Suggesting that a retreat into the ephemeral world of the internet could be the only hope for these collections almost seems spiteful.

This text isn’t a morality play laced with nostalgia for the texture of paper and the weight of a book in your hand. Libraries have serious cultural problems that go beyond the difficulties of keeping up with technological change. If digitisation could really offer a safe and productive space for specialist collections to prosper and continue to aid research and education then I’d say go for it, let the future roll on in. But I’m not sure it can at all. Not because of the logistical and legal nightmares of digitisation plans, or the high-costs associated with large-scale digitisation (though both are real concerns).3 I worry because of the Pagemaster.

Physical libraries with human librarians care for specialist collections. They provide access and assistance to those who need it, but they also protect collections from manipulation and corruption. Beyond this, vital institutional knowledge is built over time into both a staff of information specialists and the building they occupy. The internet has no Pagemasters, no guardian spirits and safeguards. Digital spaces lack incentives to care and protect, they don’t encourage the development of institutional knowledge. And this isn’t a bug of the internet, but an intentional feature, designed in such a way by its architects.

***

Jimmy Wales loves Ayn Rand. I found that out on Wikipedia.

It makes sense. Wales, the co-founder of Wikipedia, belongs to that class of Silicon Valley executives who espouse a mix of forward-facing social egalitarianism with deeply entrenched individualistic economic libertarianism. Wikipedia is decentralised with user-generated content, freed from the restrictions of the printed page and available to any individual with an internet connection. It is information free from hierarchies and gatekeepers. Lassiez-faire knowledge.

I’m not the only person to take an interest in this fact about Wales. It’s a popular topic in those deep corners of the internet where anonymous users debate on forums that comfortably retain the unpolished grey-on-grey-on-blue-grey aesthetic of mid-2000s web design. On one devoted to the revolutionary potential of crypto-currencies I found a thread where users argued under the heading “The creator of Wikipedia, Jimmy Wales, is a [sic] Ayn Rand worshipping libertarian.”4

I’m drawn to the parallels between Wikipedia and cryptocurrency. Both possess core values of decentralisation, ephemerality, rejection of traditional gatekeepers, dematerialisation, utopianism and open-source technology. The values the two share are not coincidental, but coalesce in the Objectivist philosophies of Wales’ hero. The personal and social aspects of Rand’s philosophy are a belief in rational egoism, that the only moral pursuit is the furtherance of one’s own interests. A moral society then becomes one built around individual rights and the removal of state intervention from all economic and social affairs. That Bitcoin advocates should talk about Wales and Rand at all suggests the natural intersection of two systems that owe more to the Russian-American author than we might be comfortable admitting. Beyond the previously mentioned similarities, both structures are primarily fuelled by the Objectivist’s rational pursuit of self-interest.5 That an economic market and a knowledge database could share the same core principles says a lot about the kind of engagement the internet encourages. Instead of a site of community and mutual protection, our digital lives increasingly appear to be a very self-interested place.

The last two years have witnessed a dramatic shift in attitudes towards the role of the internet in our public and private lives, in what could be the beginning of its Postmodern moment. The heady utopian optimism of Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, or the pioneers of social media has been replaced by a growing suspicion of online platforms and the companies that host them. Appeals to a neutral, post-state, meritocratic marketplace of ideas now feel like the same suite of seductive fictions that Modernism offered in the twentieth century, yet it took almost two decades and a rolling suite of political revelations and PR disasters for the problems of the internet to stick. Fallout from the political influence of social media platforms on the United States’ 2016 presidential election has cracked the veneer of neutrality from spaces like Facebook and Twitter. Just like any market, the internet has rules and norms built into its structures and processes that dictate who may prosper and who gets left behind.

Can it really be a coincidence that the predominantly western white men who built and run the cultural structures of the internet happen to also be economic libertarians? Wales, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Peter Theil. These men have all expressed support for the freest of free markets, perennially warning us of the great peril that would arise if government stepped in to closely regulate the spaces of the web. This call for unregulated libertarianism—a flirtation with outright economic Objectivism—has rarely been applied to major market systems. On the occasions it has, such as the major tax-cut experiment of the Kansas economy in 2012, nominal increases in individual freedoms have been offset by the rapid disintegration of necessary public infrastructure.6 By contrast, there appears to be a prima facie assumption that Objectivism is the natural and only system suited to digital realms. But surely Ayn Rand is the last caretaker we should want for the markets of information exchange, and of our most special knowledge.

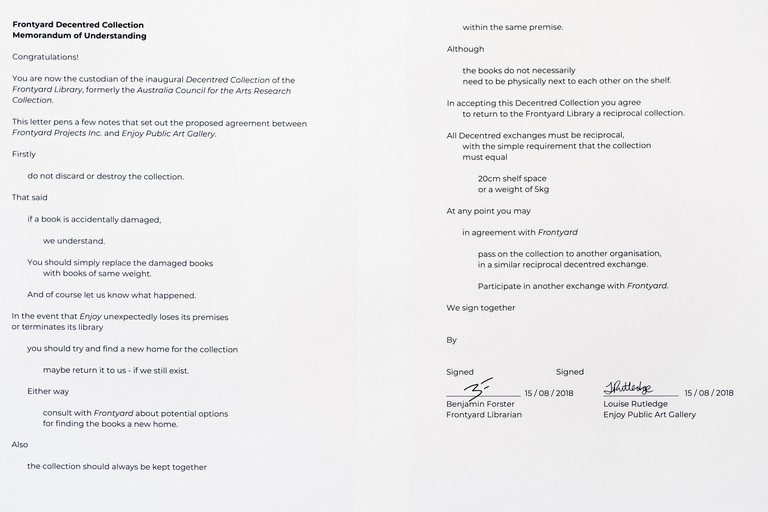

Frontyard Decentered Collection, Memorandum of Understanding, 15 August 2018, installation view. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

Libraries—particularly specialised ones—are so far from perfect. They share many problems with the art gallery. As a physical space, they are often intimidating and exclusive, restricting access on bases of class, gender, ethnicity and ability. We should always ask questions of who holds and uses knowledge, and who it has been kept away from. But digitisation cannot be the sole answer to the closure of these spaces. We should be asking whether the internet is the right space for these collections, or whether its engrained culture might corrupt them for good.

The closure of specialist libraries also signals towards the troubling metrics by which we ascribe value to knowledge spaces. As in the case of the University of Auckland libraries, closures arise from an imbalanced equation between the costs of maintaining physical spaces and the frequency with which they are used. It’s worth asking whether the increase in accessibility offered by digitisation necessarily translates into a correspondent increase in use. Perhaps a worthier line of enquiry is to question the logic of the equation in the first place. Usage is a vital metric, but what kind of spaces can we create by disrupting its primacy and introducing guardianship and community as coequal values?

The library housed at Sydney-based project space Frontyard is one possible example. Its collection of over 6,000 books were formerly in the possession of the now-closed Australia Council for the Arts Research Library. While some of Frontyard’s collection is digitised, none of it is online. Their ‘a-library’, an offline digital collection, is only accessible through a localised Wi-Fi network.

Frontyard has also embarked on a series of book exchanges with similarly focussed libraries. These reciprocal exchanges bring materiality to the centre of knowledge transference. While Frontyard and their exchange partners consider what information content each space would benefit from, the exchanges are also structured around the weight and size of the materials delivered. Knowledge that crosses borders, even oceans, doesn’t have to take the form of ephemeral streams of data. And with physical materials come the responsibilities that digitised text eschews: care, consideration, and even love. Frontyard demonstrates how digitisation, decentralisation, and physical space are not necessarily exclusive concepts. Their considered approach retains a sense of place, community, and responsibility.

On the 22nd of September 2018, Samoa House Library opened on Karangahape Road in Auckland. Organised by Elam School of Fine Arts students who protested the closure of their own specialist library, Samoa House is a community driven alternative. Their physical collection exists by donation, and is catalogued in a way that cites donor contributions. While it is still establishing itself, Samoa House looks to be more than just a specialist library. With an active public programme and accessible spaces, its facilitators look to engrain the space and its collection into their community.

With a funding model that looks more like an artist-run initiative than a traditional library, Samoa House faces a unique set of economic challenges. A network of sponsors and donors, no matter how dedicated to the cause, will never provide the same long-term security of tenure as a council or university. There is potential, however, for this kind of physical precarity to foster continual innovation and adaptation in the maintenance and growth of specialised knowledge.

These two examples offer a different vision to the technological determinism of pure digitisation. The number of specialist libraries facing closure will only increase in the coming years, making adaptation an unavoidable part of safeguarding such collections. But these changes don’t have to move in one direction, and conform to one set of principles. The self-interest and isolation that define the spaces of the internet aren’t the only haven for specialist collections. While elements of digitisation and online access are inevitable, options are available that hold fast to the belief that libraries are sites of community, education, and support. And in all cases, if specialist libraries are to survive as physical locations they require the continuing guardianship and care provided by information specialists. Stated otherwise, you can’t have libraries without Pagemasters.

-

1.

James Matarazzo and Toby Pearlstein, Special Libraries: A Survival Guide (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2013).

-

2.

Tara Murray, “When a Library Shuts Its Doors: Collections and Information Services After a Library Closure,” Journal of Library Administration 54:2 (April 2014): 148.

-

3.

Murray, ”When A Library Shuts Its Doors,” 150.

-

4.

“The creator of Wikipedia, Jimmy Wales, is a Ayn Rand worshipping libertarian,” Bitcoin Forum, accessed 12 December 2018, https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=96471.0.

-

5.

In The Wikipedia Revolution: How A Bunch Of Nobodies Created The World’s Greatest Encyclopedia (New York: Hyperion, 2009), Andrew Lih argues that the apparent altruism of Wikipedia contributions are forms of self-satisfaction.

-

6.

Howard Gleckman, “The Great Kansas Tax Experiment Crashes and Burns,” Forbes, accessed 18 January 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/beltway/2017/06/07/the-great-kansas-tax-cut-experiment-crashes-and-burns/#249a735f5508.