Exhibition Essays

Too Orangey for Crows

September 2009

Re: don't forget your first question

James R Ford, Jeremy Booth

Jeremy Booth:

So James, I was thinking recently about exhibition press releases. The way that they sometimes never really saying anything, in order to really say something. In passing I came across the press release from your 2009 show, Too Orangey for Crows, and found it interesting that the press release described the work as operating in a self referential, void space. In transition. Was I right in writing this, or was this an over simplification?

James R Ford:

I think you’re correct in the use of the word transitional. The show was situated in a kind of in-between space. Being my first solo show in New Zealand and taking place only two months after moving to the country, the work on show was a mix of ideas and pieces formed and made partly in the UK and partly in NZ. The work that played most on my move between countries and art worlds was Little Endeavours, the most under stated piece in the show. In its fake tabloid headline format it basically conveyed the way that, as an emerging artist, no one really noticed I was leaving England and no one (in the art scene) cared that I was coming to New Zealand. So it was no surprise that my pathetic parade of toy boats in the Thames went unnoticed by the public. The painted sign I exhibited — Artist Launches Toy Boats into Thames — was an ironic testament to that.

JB:

I wonder what became of them, bobbing with naivety alongside debris and treasure is how I imagine it. I guess it doesn’t matter. It seems that as well as the irony of launching the boats, this was also a gesture to the tides of chance, to a moment of action shaped by circumstances both before and after the act: both of which were most likely outside of your influence. It’s interesting to consider this self-perceived, non-consequential departure and arrival within an historical perspective, in that artists were of the highest esteem and importance on such expeditions as that which the work references.

JRF:

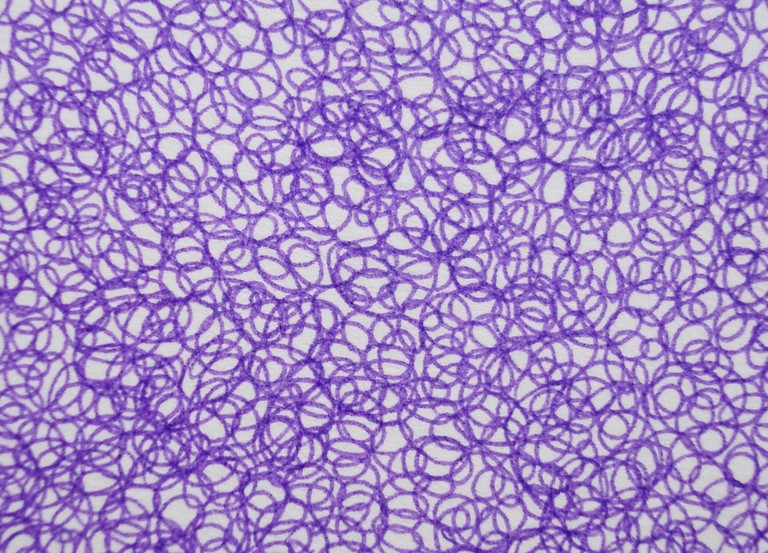

I assumed the boats would either be washed up on the banks of the Thames, stuck at the Thames estuary, or, ideally, floating off into the North Sea in search of New Zealand. Like Captain Cook, hence the title (his boat was called HMS Endeavour). You mention chance and this is present in a lot of the works I do — call it chance, randomness, good luck/bad luck, chaos. My method of chance is usually situated within an ordered structure. For example the Scribble Fields works which were also in the show. The contrast between geometric shapes and the free-flowing scribble loops contained within. They look ordered from a distance, seemingly basic colour shapes of triangle, circle and square. But on closer inspection the simplicity gives way to an obsessive, labour intensive mass of mark making.

JB:

Scribble fields, like going berserk on a budget. I like the idea that complexity can be masked by our own limitations. In this case, the depth of the exhibition space, and the viewer’s relationship to it.

JRF:

The initial idea of the Scribble Fields was to set up a paradox: that which is supposed to relieve boredom actually causes it, thus defeating its own objective. Over time that developed in being more about the mark making, colour composition and types of containing shapes. I’m actually leaning toward the ideas of masking, covering up or even erasing as the next step forward. Perhaps in terms of the visibility of the artist in the work. I’m not sure yet but it has potential for development in interesting ways.

JB:

Only boring people get bored, right? Somehow I think this doesn’t apply to you. It seems like this kind of, almost melodramatic action, that sees your toy boats cast off in parred back extroversion is located back here, quite sharply, with the scribble works. They trivialise their own being. Take Pink Scribble filling a White Triangle, for example. The cumulative, absent minded doodling of what could be any teenage boy, gingerly attempting phone-line courtship, seamlessly fills a shape that was never there to begin with. That you can maintain such detached tedium, and end up with something austere, hard on the eye, is remarkable.

JRF:

“Trivialising their own being” is a great description. You could say it’s a trait of the British, self deprecating. My work can have a lot of Britishness in it, stemming from reminiscing on my childhood and the patriotic mood of an 80s England, with street parties to celebrate the wedding of Charles and Diana. I also remember a lot of 80s music, even from a very young age, and this was part of the development process of the Mollie Boogie work. I always wanted to produce a piece based around the fact that you can remember the exact lyrics to songs that you haven’t heard in a decade. After the clicks and twangs of Hit Me With Your Best Shot I was interested in utilising and twisting the playing criteria of another music-based video game. When I saw the track listing of the Wii Boogie game it all came together. These conceptual ideas along with the growth development of my first child (who would some day look back on the music of the 10s), formulated the Mollie Boogie work. It was a bonding experience and a showcase of my raw, unedited singing talents.

JB:

They do say that children love the sound of their parents’ voices, tone-deaf or not. But without even a backing track the onus certainly was on your vocal chords. How do you think your “unedited” singing abilities impacted on the viewing experience of this show? Standing in the space these songs became literally a soundtrack for engaging with the other works — from Britney Spears to the Jackson Five. Was the intention to get inside the viewer’s nostalgic headspace space as well, or how did you see this operating?

JRF:

I hoped that my singing inability would make it even more personal, but also cringe-worthy to listen to. To make the viewer want to stay and watch to see if the unborn child would kick and react, but at the same time to have the urge to move away because the singing was annoying them. And for those who could bear my voice, I wanted them to sing along, almost subconsciously, as those tacky, ear-worm style pop song lyrics came burrowing to the surface of their minds.

JB:

Mollie Boogie was in this sense quite a bodily, relational work, offering as you say a glimpse of in utero action for those with the patience for the warm skin tones of your wife’s bulging belly. And here the in-transit idea comes through, perhaps most potently. This work was projected with proximity to the record works, It’s a kind of magic, that seemed to command the show, spatialy. Was this like an outpouring of this sense of the musically, pop-culturally, paginated self. Or how should we read these objects with the audio in our ears while viewing them?

JRF:

The two works were never created to sit next to each other but I felt it worked in this scenario. The idea of judgement is conveyed in both. The viewer judging my karaoke singing voice and, in It’s a Kind of Magic, a Magic 8 Ball judging the music from my childhood. And therein lies the randomness again, the judgement of the records is made arbitrarily by the ball (although supposedly it has a mind of its own). Sometimes the ball’s opinions matched mine; sometimes it got it wrong, in my opinion. If only the ball had to explain its valid reasons, like a contestant nominating a fellow housemate on Big Brother.

JB:

The non-descript nature of an 8 Ball also seems to echo the fanciful reasuredness of many of the pop songs that appear as karaoke tracks in the video work. Whether in heartache, lament, love or speakeasy naivety, the songs more seek to connect with the listener on common ground rather than through meaningful engagement. In the same way that an 8 Ball tries to cover its bases [Will Rachel be my love? ... ‘It may come to pass’, I knew it]. You know what I mean, it’s more like a television psychic reading an audience member through intuition and a process of elimination, than the transgressive meanderings reality television producers acheive in pitching personalities against eachother; with which reality becomes what is most likely, and even then tweaked on post-production. I guess what I’m trying to say is that your show placed the artist as central, but who is the artist then? And what difference does it make anyway. The viewer could just as likely be the subject.

JRF:

The subject matter of my work has always been routed in everydayness: accessible, readable and do-able. And along this path, on occasion, my projects have been collaborative with the viewer/participant becoming the artist. The most recent example of this was the Smash N Tag event as part of the Primera Disaster piece. Through arts promotion and media publicity I managed to gather a crowd on a disused lot in town, to help publically destroy my cursed Nissan Primera car. I provided safety gear, sledgehammers and spray paint, and there was the option to bring along your own weapon. Even on the day of its death, the curse of the car summoned rain. Participants donned hoods and brought weapons such as axes, bats and even an old Macintosh computer to attack he car with. Each volunteer had a minute to do whatever they wanted to the car, as long as it didn’t cause an explosion. The result is a collaborative (anti-) sculpture formed by public, cathartic action.

JB:

These elements — the everyday, the do-able — bring a sense of immediacy to your work... particularly for the viewer, as the viewing experience quickly becomes about finding ones place amongst the action, or experience, as opposed to wracking ones brain for understanding. And with this, it comes anyway. It’s almost a year to the day that your show at Enjoy opened. With this idea of transition that became fabric for the show now complete, how might you have worked with audiences if your show, say, was to open in two weeks time?

JRF:

If my show was in two weeks time I would be panicking ha! I’ve settled a bit in NZ now and, after Primera Disaster, feel a real connection to the arts scene. My latest work is involved with the results of misbehaviour, defacement and boredom. ‘The devil makes work for idle hands’. The possibilities of these things within the works but also of cheeky treatment of the viewer. The physicality of the viewing of work has always interested me, and the way that the viewer can be coerced into performing actions or reacting in a certain way. I remember a work I saw at a small gallery in Vyner Street, London, a few years ago. The white walled room contained only one element, what appeared to be a peep hole at around waist height on one of the walls. Each of the people before had gone over to the hole, bent over to peer through and then burst out laughing. So I went over to the hole, bent down and realised why people were laughing: I was now closely examining a black painted circle! I enjoy that kind of viewer interaction. It may not be to that extent in some of my new work but the gently-guiding-ness of the viewer to a place (physically and conceptually) of my choosing will be present. As an artist I feel that your work is always leading the audience somewhere.

JB:

And do you think that this a reciprocal relationship? An ongoing dialogue? Does the audience also lead, or coerce the artist in a sense?

JRF:

It’s definitely reciprocal, as the audience reaction/involvement can determine or influence what I do next. If the viewer doesn’t “get” what was supposed to be “got” from one of my works, I may want to revisit an idea or develop it in a different direction. For now, the direction I’m heading will either be based in bore- dom, or badly behaved...