Exhibition Essays

This is a mirror

March 2020

This is a mirror

Maria Samuela

Teuane Tibbo, Untitled (Monkey See, Monkey Do), date unknown, acrylic on board, collection of Malcolm McNeill and Teuane Tibbo, Untitled, 1967, oil on board, collection of Jowitt family. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

This is a library showcases the work of four Pacific women artists: Teuane Tibbo, Claudia Jowitt, Christina Pataialii, and Salome Tanuvasa. Curated by Hanahiva Rose, it explores ideas of memory, place, and home, connecting these artists from multiple generations primarily through the paintings of Tibbo. Born in Apia in 1895, Tibbo was one of the first Pacific artists to exhibit in Aotearoa. Her first show was in 1965 at the Barry Lett Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau, when Tibbo was in her early 70s.1

I experienced This is a library online, safe at home during self-isolation. Scrolling through the images, I’m struck initially by Tibbo’s depictions of island life. Although flat and static on my computer screen, the paintings are, nevertheless, lively. They include portrayals of tapa-cloth making, the family home, the land, the sea and community—all scenes I imagine would have been familiar to my parents and ancestors. On the surface, the artworks are colourful and idyllic, born out of memories from Tibbo’s childhood and young adulthood. But as I’ve come to learn about the artist’s life before Aotearoa, the paintings, for me at least, seem to harbour a harsher truth. After living in Fiji, and through tumultuous times during some of Samoa’s harshest periods of history, Tibbo settled in Tāmaki Makaurau with her husband and eight children. It’s her pioneering spirit and strength, I think, that breathes vitality and depth into her art, and, alongside the island settings of some of her paintings, it’s what makes me remember my mum.

Mum came to Aotearoa around 1950. She was 16. I remember that age specifically because I can recall thinking, at the age of 16, that neither of my parents would have let me leave home, let alone the country to start a new life. It would be thirty-seven years before Mum returned to her homeland. I went too. It was my first time in Rarotonga, and I was still in my teens.

Mum showed off her land to me, walking on the grassy path that led us from the sea to the foot of Te Manga. A concrete foundation, the beginnings of a new home, had been laid near the beach to catch the sun. I remember her plucking an orange from a tree planted by the family caretaker, and then watching her eat it, peeling away the pith, sundering each segment. Dead coconuts knocking at our feet. The sound of the waves whistling around us. The house she grew up in had been torn down many years before. The new home by the seaside would never get built.

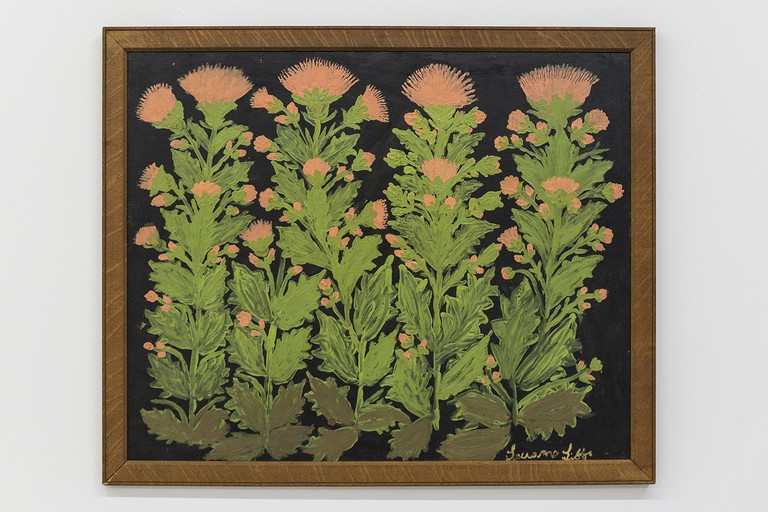

Teuane Tibbo, Opium Poppies, 1968, acrylic on board, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago, Ōtepoti Dunedin. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Of Tibbo’s paintings, Opium Poppies (1968) is my favourite, closely followed by Flowers II (1975). I open each of the images into separate tabs, isolating them from the rest of the website. Of course I can’t see the ridges or the density of the paint on the canvases as sharply as I would have had I been standing in front of them, but I can sense it, in the different shades of green and yellow and apricot, the colours of the plants popping against the contrasting backgrounds. They remind me of the tivaevae Mum sewed when she was a young woman, one of the many talents she brought to Aotearoa. Viewing the paintings online in this way feels a bit like flicking through the pages of a photo album, reading a curated story in pictures.

Whenever I think of Mum, of how she was before she became a mother, I invariably remember her classic black photo album. Its thick black pages slotted between thin sheets of archival paper. The ageing booklet showcasing snippets of her life as a young woman, memories she’d created before she met Dad. Dressed in piupiu to perform Māori waiata. Draped in a homemade satin ball gown, white evening gloves pulled past her elbows. In her spare time she sewed tivaevae, the vibrant bedspreads that would decorate our rooms. By day, she worked as a machinist, sewing military uniforms with other women like her, who had also migrated to Aotearoa from the Cooks. By night, she sat alone on a single bed in the dark, the light from the moon, or a streetlight, streaming through her bedroom window. At least, according to my memory of that particular photograph. Her first home in Aotearoa was a boarding house in the city.

Looking at Christina Pataialii’s paintings of her nana, Nana and Boy’s too young to be singing the blues (2018), is a bit like gazing at those photographs of Mum. The lines are bold and striking, the sharp, contrasting borders mirroring, in my mind, the different realities of my world and the world of my mother’s. It’s difficult to tell how large the portraits actually are, but like I do for Tibbo’s artworks, I can imagine their immensity based on what they make me feel. Created with house paint, acrylic, and charcoal on drop cloth canvasses—materials you might find when decorating your home—the blazing red markings that make up her nana have been constructed at the outset and carried through the two portraits, suggesting to me that her nana comes first. Anything that comes after is built in around her, essentially making her the centre of her world.

Christina Pataialii, Nana, 2018, acrylic, house paint, charcoal on drop cloth canvas and Christina Pataialii, Boy’s too young to be singing the blues, 2018, acrylic, house paint, charcoal on drop cloth canvas. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

This is a Library links contemporary artists Pataialii, Jowitt, and Tanuvasa to Tibbo’s work posthumously. The connection between the artists isn’t hindered by time or space or generations or death. In fact, it’s strengthened by this fact, as if this distance and demarcation creates an extra element to the relationship, an added perspective that otherwise couldn’t be there.

Nearly 10 years ago, my brother Steve posted a video link to his Facebook page. The clip was from YouTube, an excerpt of a documentary filmed in 1951. It was the first time I’d seen my grandfather in the flesh—virtually, that is; I’d never even seen a photograph of him. He died many years before I was born, and all I knew about him were from family stories told by Dad. In 1951, no one could have predicted my connecting with my grandfather through social media. Or know that by the time I watched that video clip, I would have already lost my dad.

My grandfather wore white that day. His shirt—sleeves rolled to his upper arms—was tucked into his trousers. They looked baggy and too long and like they’d been folded inwards at the ankles. I imagined my grandmother hand sewing the cuffs in place. Unhooking his hat from a nail on the wall. Straightening his collar before letting him leave the homestead.

He was smaller than I expected, and quick on his feet, like a rugby winger. A natural dancer—that was obvious. A gifted orator, I’d been told. Clutching a stick that extended above him, he welcomed the visitors to the island my dad grew up on. Hips swaying to the beats of the pate, he sprung left to right on the tips of his toes, his shoes—not white—shuffling on the grass.

Salome Tanuvasa, untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy Cheska Brown.

In a sense, I interacted with my grandfather for the first time online, experiencing his digital reality at home. Salome Tanuvasa’s art, whose work in this exhibition was produced at Enjoy, is a direct interaction with the art of Tibbo. Her physical proximity to Tibbo’s art played an important role in the creation of the five untitled pieces included in the show. The markings are fearless, vivid patches of colours and shapes that speak to Tibbo’s paintings uniquely and personally. I feel like I’m eavesdropping on a private conversation, like hearing my parents speak in their mother tongue.

Claudia Jowitt’s pieces, on the other hand, include three-dimensional artworks made up of coral and other natural materials—paua and kina shell, qari (sea crab) and cawaki (sea urchin), civa (mother of pearl) and freshwater pearls—hemmed in by clay framing. Her paintings, pastel watercolours on Bristol board, are, for me, like two-dimensional versions of her sculptures in the exhibition. Again, I examine each piece individually, isolating each one in a separate tab on my computer screen. The photographed images manage to capture the layers in the sculptures, and it’s easy for me to imagine them as small islands, abundant and thriving with nature.

Taking inspiration from materials retrieved from the sea, these pieces take me back to Tibbo’s scenes of island living. The light colours remind me of the white sands on the beaches of Rarotonga, the sculptures connecting the land to its people, reminiscent of the island scenes I watched in that video.

Claudia Jowitt, Lomaloma I, 2020, acrylic with paua shell & Fijian vau on panel with painted clay frame. Image courtesy Cheska Brown.

My dad loved to dance, but that was the only similarity I could see between him and my grandfather. I never saw my grandfather’s face in that video clip. The camera lens was angled towards the back of his head. The brim of his hat was so wide and concealing that I couldn’t even tell if he had any hair. What I could see instead were the faces of the officers and sailors, and presumably their wives, and their animated reactions as they watched my grandfather dance. I envied them. It would be years before I got to see his face too.

In the year of that video clip, 1951, my dad would have turned 16. Not anybody’s father yet, still living on Mauke, his life in Aotearoa firmly placed in the future. I looked out for him, or traces of him, studying the faces of my extended anau. His prominent forehead. His wide eyes. His thick mane of hair. It was hopeless. At 16, my dad was a different person to the man I knew growing up. And this man in white with the nimble dance moves felt like somebody else’s grandfather.

This is a Library does more than revive the paintings of Teaune Tibbo, introducing her work and life to a new generation, while also celebrating the art of contemporary artists Claudia Jowitt, Christina Pataialii, and Salome Tanuvasa. It holds up a mirror to the rememberings of our past, our relationships with our home, our land, and our people. It connects generations, defying the limitations of space and time, and it acknowledges our similarities and differences, rekindling our sense of belonging and being.

This is not an ocean, this is a rented house

this is not a hand, this is a library

this is not the sky, this is a grandfather clock

this is not a child, this is a mirror.

—Jim Vivieaere, This is not an ocean, 2007

Teuane Tibbo, Claudia Jowitt, Christina Pataialii, Salome Tanuvasa, This is a library, curated by Hanahiva Rose, 2020. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

-

1.

“The return of Teuane Tibbo,” New Zealand Herald, 28 April, 2002, https://www.nzherald.co.nz/lifestyle/news/article.cfm?c_id=6&objectid=1842350.