Exhibition Essays

Typical Relics

March 2015

Fashion, Landmark, Paper, and other Typical Relics

Kerry Ann Lee

“So you’re responding to Jade’s work that responds to Beijing?” asks Martyn. Yes, but I only saw it for a brief second. “That’s okay,” assured Emma and Louise, “It was only up at Enjoy for a week”.

Blink and you missed it, because the magic of all this is in the moment. Jade’s involvement in the fashion industry has long been a point of reference in her artwork and in late 2014 she went to China to see what consumerism with Chinese characteristics might look like.1 The resulting work, Typical Relics was created during her Asia New Zealand residency at Red Gate Gallery and exhibited at the Comme des Garçons concept store in Beijing from February – April 2015.

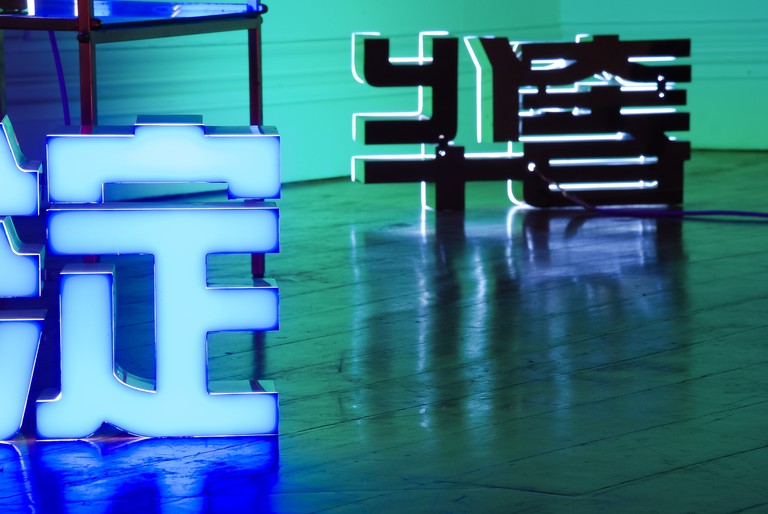

Jade presents Beijing as an eternal night-time showroom, illuminated by colourful signs and plastic lightbox wonders featuring English and Chinese characters. Her work reveals her interest in the taste-making properties of the luxury fashion industry operating from within the Chinese moment. Fashion is essentially designed to reinvent and outmode itself each season, but more resonant are the translations (and subsequent mistranslations) of both high and low production and consumption values occurring between the East and West.

Through Typical Relics, I was instantly transported back to the contemporary Chinese city, the one I met for the first time in 2009. Those glowing characters were cryptic everyday reminders of where I was. I’m Chinese but I’m not Chinese and, as a Westerner, my semiotic relationship with this place is founded on errors and misreadings. But then again, I might be quite typical in my Chineseness to be mucking around with cultural contrasts and contradictions.

China has always been red hot. The rapid shift from little red books to little red handbags occured in a flash of time following the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). Through social reforms and the establishment of China's socialist market economy China was opened up to global markets in the late 1980s. New York fashion maven Iris Apfel has famously extended architect Robert Venturi's playful aphorism "More is more" into "More is more and less is a bore."2 The Chinese equivalent of this could be former leader Deng Xiaoping famously being quoted as saying "To get rich is glorious!" (simplified Chinese: 致富光荣; pinyin: zhìfù guangróng;) in Western media. There is no proof that he actually said this, but has since been a popular ideal amongst an emergent Chinese middle class.3 If you also subscribe to these late-capitalist maxims, then the Chinese city will open its pearl and gold-encrusted gates to you.

My friend Ginny in New York told me that I’d be rich in China because my money is worth five times as much. Free trade is encouraged and there’s plenty of support for foreigners wanting a share of the Chinese market. Even fake business advice can be useful. So in theory, as a foreigner with an economic upper hand, you can participate, thus in turn, get to know the city. As author Pico Iyer says:

The New China prefers to keep its rendezvous with the West strictly organized and closely chaperoned with a series of blind dates on which the two parties may inspect one another from a safe distance, swap reassuring smiles and then go their separate ways, separately enriched.4

Trade is communication and in the Chinese city, shopping and bargaining is a way of life. In reality, retail fun was actually wasted on me. I often felt exhausted, as if I was preparing for battle every time I went into a shop with over-eager storekeepers running at me, waving calculators in hand, wanting to offer the ‘best discount’. What this also means—as Jade, myself and any foreigner who’s lived in China knows and can tell you—is another type of ‘crisis’, where being a Westerner (regardless of background) is instantly associated with constant opportunity.

There is a common public misperception of the chinese word 'crisis' (simplified Chinese: 危机; pinyin: weiji), the word is frequently invoked in New Age-y Western motivational speaking as it is composed of the two Chinese characters that can represent 'danger' and 'opportunity'.5

Jade’s Beijing is a city of surfaces where things are not what they seem—faux glamour, imitation sporting goods, phony iPhones and repro designer shoes mass-produced by the gazillion. China is the world’s factory where you will find copies of original designs, mass-manufactured as genuine items for growing consumer market demand. Design production services a very Chinese-style desire for closeness to Western high life, if the abundance of domestic ‘fake market’ trading (in real life and online) is anything to go by. Brand labels may have Western names and appearances, but are uniquely Chinese in their manufacturing and commercial deployment. One of the first things I learned from my Chinese teacher Gao Bing was, “zhen de jia de? ” – ‘Is it real or fake?’ (真的假?). You can hear this echoed on the street, in shops and between friends. This is hyper-consumerism at work where the mighty bottom dollar rules. Trade is communication.

Jade collapses both old and new references to reveal such contradictions operating on the showroom floor. Take for instance the shows title, Typical Relics, taken from a wall sign describing the Terracotta Warriors in Xi’an. Jade has reframed this pairing to reveal ironies she uncovered in Beijing–from the beautifully foiled packets of cigarettes, the monolithic yet empty ghost skyscrapers, to the slick luxury fashion items displayed beside her hidden hand-laboured art pieces at the luxury design store where the work was first exhibited. Relics are contextual and can be sentimental or historical. Jade’s subtle referencing to light pollution in the city through the defused coloured lightboxes and her hand-crafted vinyl floor installations, designed to wear down over time, were a further subversion of the pristine Comme des Garçons showroom.

Money talks but sometimes all we have is words. ‘Engrish’ (or ‘Chinglish’) is the slang for corrupted English translations of Chinese characters commonplace throughout Asia and on the Internet. For a good dose of this, check out the cult website, Engrish.com. Such mistranslations are a source of constant embarrassment for the Chinese government who, in the interest of good taste, attempted to eradicate Engrish on the world stage during the 2008 Beijing Olympics and 2010 Shanghai World Expo.6 In a perverse way, Engrish totally makes sense to me through the earnest-ness and human qualities shown in these grammatical errors. In the Chinese city, sometimes it’s all we have to communicate with. The playful liberties taken with our precious English language enable creative understandings of each other. It’s this humour that eases naturally difficult communications.

Jade too encountered this language barrier in her piece Transform. After much discussion and guessing games with her Chinese team to accurately locate the Chinese characters to translate this idea, the translation shifted from specific to universal, arriving at a combination of the characters for ‘change’ and ‘body’ to best describe this word.7

I went searching for media about Typical Relics in China, online at Baidu.com (aka ‘Chinese Google’). I found Chinese magazine articles that I translated using Google Translate, the results of which, screamed at me in Engrish: “Fashion & Art cross-border integration! IT Beijing Market art gallery artist Jade Townsend settled in particular works, creating a new visual space”8. Jade was described as a ‘Sina Fashion Dialogue artist’ and one article was titled: “What makes While 27-year-old woman came to Beijing fashion landmark paper carry handle!”9 But I got it. And as any Westerner in Asia can attest to – you can actually understand a lot with very little. Ruin, Marble, Statue... found words lifted from fixed baselines, recomposed together in a room free from grammatical conventions. This is the new visual space created by Typical Relics.

Many cultural signifiers get scrambled in translation when viewed inside a store or a gallery, or on the surface of the Chinese city, and can appear unfamiliar from a distance. For instance, if you find yourself at People’s Park in Shanghai on the weekends, you might come across a marriage market, where desperate parents pin up pictures of their unwed children to a wall and network with other parents to make a match, a throw back from arranged marriages of yore. Making meaning, and making art in China can be a process of match-making, or mis-match-making if you will. We have the luxury as Westerners to be collagists, to make our own strange matches, to travel from street markets to luxury stores to pick and choose items to reconstruct and change ourselves. Typical Relics reminds us that the desire to refashion oneself is a mirror to what’s happening in the now, where the new Chinese city sheds its old skin and re-emerges from itself newer and bolder in each defining moment.

-

1.

Jade Townsend, “Typical Relics”, Artist talk, Enjoy Gallery Wellington, March 26, 2015. https://soundcloud.com/enjoy-public-art-gallery/jade-townsend- typical-relics

-

2.

Advanced Style, “Iris Apfel: “More is more and less is a bore.” http:// advancedstyle.blogspot.com/2012/10/iris-apfel-more-is-more-and-less-is- bore.html

-

3.

Evelyn Iritani, “Great Idea but Don’t Quote Him,” LA Times, September 9, http://articles.latimes.com/2004/sep/09/business/fi-deng9

Helen H. Wang, The Chinese Dream: The Rise of the World’s Largest Middle Class and What It Means to You (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010).

-

4.

Pico Iyer, Video Night in Kathmandu and Other Reports from the Not-So-Far East (UK: Bloomsbury, 1989), 124–125.

-

5.

Victor H. Mair, “Danger+Opportunity≠Crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray,” September 2009. http://pinyin.info/ chinese/crisis.htm

-

6.

BBC, “Beijing stamps out poor English,” October 15, 2006. http://news.bbc. co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/6052800.stm

Andrew Jacobs, “Shanghai Is Trying to Untangle the Mangled English of Chinglish,” New York Times, May 2, 2010. http://www.nytimes. com/2010/05/03/world/asia/03chinglish.html

-

7.

Jade Townsend, “Typical Relics”, Artist talk, Enjoy Gallery Wellington, March 26, 2015. https://soundcloud.com/enjoy-public-art-gallery/jade- townsend-typical-relics

-

8.

Haibo.com, http://life.haibao.com/article/1745065.htm

-

9.

Sina, http://fashion.sina.com.cn/s/ic/2014-12-05/1656/doc-iavxeafr5810162.shtml