The Occasional Journal

Local Knowledge

July 2016

-

Editorial

Emma Ng -

Diversifying and moving through the hidden city

Gradon Diprose, Kelly Dombroski -

Don't fucking die today! Putain, ne meurt pas aujourd'hui!

Janet Lilo -

Stitching the Street

Sian van Dyk -

In your belly, a vague place

Ngahuia Harrison -

The Fair in May

Laila O'Brien -

No Stone Unturned

Aliyah Winter, Angela Kilford -

Kinetic Rituals

Balamohan Shingade -

At the still point

Elisabeth Pointon

Kinetic Rituals

Balamohan Shingade

The world of people and that of gods exist, for the most part, in parallel, but there are points at which these worlds coalesce: points at which the gods come, as it were, to a focus. Mountains, caves and rivers are the dwelling-places of the divine. Shiva resides in the cavities of Mount Kailasa, the Oreades populate the Anatolian mountains, Hinekorako lives in the rivers of Te Reinga. These are our places of worship and it is to these places that we journey as pilgrims.

There are many different ways to be mobile and move through the world, to know our surroundings and to be in our landscape. I participated in my first great hike in Fiordland over summer this year, and was reminded of my father’s pilgrimage through the Western Ghat mountain ranges in Kerala. I wondered about the likeness of our experience. Although both our journeys traversed mountainscapes, the way in which we did so would have been vastly different. For one, my father was on a religious pilgrimage with an ascetic fervour, whereas I was a tourist in the wilderness. His destination was a shrine to Ayyappan in the Periyar Tiger Reserve, whereas mine was Piopiotahi or the Milford Sound. He was robed in the black cotton of an ascetic with a garland of tulasi beads on his chest and a sack on his back, whereas I was decked out in specialized tramping gear—albeit second hand acquisitions—from New Zealand’s most upmarket shopping district. Our preparations were different too. I joined a gym to train for two months prior to the trip, and experimented with electrolytes and protein shakes. My father observed an austere lifestyle for forty-one days, becoming celibate, letting his hair grow long and abstaining from eating meat. After his twice-daily cold bath, he would smear his forehead with ash and sandalwood paste, and recite sharanam, sharanam, sharanam. In the end, we would both have walked for four days resting overnight at temporary shelters. The nature of our experience, though, would have been wholly divergent.

Considerations of pilgrimage have been a key thread in my creative practice. Perhaps it has been my way of recognising an element of religiosity in art, a way of acknowledging the latent faith-based system upon which art practices rely. But rather than going on solo spiritual journeys like those of pilgrims in India, my projects have been a way of bringing people together. Resisting the colonial image of ‘a man alone in nature’, whose legacy inevitably colours our view of a spiritual pilgrimage across a New Zealand landscape, my projects have sought to engage people on a socio-cultural level.

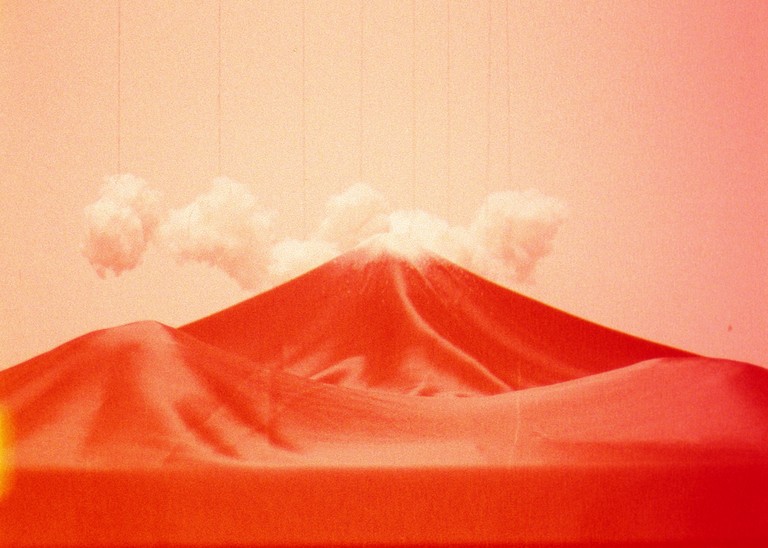

On 15 July 2012, I invited artists, curators and makers to journey with me from Auckland to Mount Taranaki and back, travelling by a Voyager Coachline from dawn to midnight. Each participant was invited to contribute something as a trace of the journey. Thirty-six people offered material responses in the form of drawings, prints, photographs, video or audio recordings, performances, objects and food which have been installed in multiple gallery settings as Thirty-six Views of Mount Taranaki. The tour-cum-pilgrimage wove together a number of threads: the status of Taranaki as a mountain deity in Māori mythology, its use as a stand-in for Mount Fuji in The Last Samurai and the resulting celebrity tourism in the district, the many artworks that have been made in awe of Fuji including Hokusai’s famous print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Balachander Shingade, Thirty-six Views of Mount Taranaki curated by Balamohan Shingade, 2012.

Emil Dryburgh, Thirty-six Views of Mount Taranaki curated by Balamohan Shingade, 2012.

Rose Thomas, Thirty-six Views of Mount Taranaki curated by Balamohan Shingade, 2012.

In the following year, on 18 August 2013, I journeyed with a group of fifteen by foot, tracing the previous sites of RM Gallery in Auckland. The founding director of RM joined us to ignite conversation around each landmark. We tied a piece of red fabric at each stop, placing remnants of the walk. Yātrā, which is a Sanskrit term connoting a departure or a pilgrimage, acknowledged RM as a series of sites imbued with cultural vibrancy over its sixteen year span. Room Yātrā aimed to collapse time as the pilgrims traversed a variety of spaces. As one walker later wrote, “you are in one room, but experiencing another… this is a correspondence of sort, one that uses history to crunch together or, perhaps expressed in a more gentle fashion, be folded into the present. It’s a form of active psychogeography too.”1

Balamohan Shingade, ‘Room Yātrā’, as part of Expanded Map curated by Ruth Watson and James Wylie. Auckland: RM Gallery, 2013.

Balamohan Shingade, ‘Room Yātrā’, as part of Expanded Map curated by Ruth Watson and James Wylie. Auckland: RM Gallery, 2013.

Balamohan Shingade, ‘Room Yātrā’, as part of Expanded Map curated by Ruth Watson and James Wylie. Auckland: RM Gallery, 2013.

Balamohan Shingade, ‘Room Yātrā’, as part of Expanded Map curated by Ruth Watson and James Wylie. Auckland: RM Gallery, 2013.

Having conducted these experiments, I am doubtful whether it is possible to really undertake a pilgrimage in twenty-first century New Zealand.2 Perhaps the limitations of Western conceptions of travel, and New Zealand’s avowed secularism leave little room for religious pilgrimage to arise. Visions of travel in New Zealand emphasise, for example, appreciation of one’s surroundings and attention to sensual experiences, while seeking to mitigate physical discomfort and psychological hardship. The tourist’s gaze looks outward towards the landscape, or the excitements she encounters, and it is the outside world which is supposed to catalyse a transformation within her. The pilgrim’s gaze, however is directed inward at her own bodily and psychological functionings, and the difficulties she experiences are necessary elements on the path to self-transformation. The sense of religious fervour which motivates some laypeople in India to undertake grueling journeys is a very different motivation to that of the tourist, whose resistance to the hardships that journeys of self-transformation usually entail undercuts her ability to invest herself wholeheartedly in the process. While stories like Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2006 blockbuster memoir, Eat, Pray, Love might suggest an elision of the tourist journey with the spiritual pilgrim’s journey, we must not be too quick to assume that the two practices are compatible.

One might protest that tramping must be New Zealand’s form of pilgrimage. It certainly seems to fit the description from a distance, being a process-focussed activity with no apparent end goal (I would argue that ‘conquering the landscape’, in the spirit of colonial explorations, still persists). But its close ties to the tourism industry, the amount of high-tech equipment needed, the level of physical comforts, the culture of risk management don’t seem to correlate with the aims and processes of the pilgrim. While New Zealand’s majestical landscapes seem to make our country the destination for those seeking a spiritual communion with nature, visions of the sublime should not obscure the economic realities which allowed such landscapes to be preserved. Far from the beneficent motivations of concerned environmentalists, the ideology which saw the creation of national parks in the nineteenth century was tightly connected with commercial interests. Yellowstone National Park in the USA, widely considered to be the world’s first National Park, required the construction of a railroad, hotels, and the exile of numerous American Indian groups before it was opened for visitors.3 The park served the needs of a tourist class: people from the city with enough money could escape the turmoils of modern life to find solace in an ‘uncorrupted’ wilderness. The trampers that fill the walking routes of New Zealand parks today come from a similar group, largely Pākehā and middle class (although a large part of the tramping population is now comprised of international tourists), and the activity itself continues to operate as a form of quasi-spiritual tourism.

Another reason that pilgrimage seems to be an impossible task for this time and place is that our sense of wandering and discovering is mediated by things already known. Derived from the Latin peregre, a pilgrim is a wanderer or stranger from abroad. If, in former times, a pilgrim’s roamings were improvised, those of modern pilgrims are comparatively purposeful and predestined. The pilgrim abandons her home with a destination in mind—Haridwar, Lumbini, Santiago de Compostela, Mecca or Mount Taranaki. It seems that, in this age more than any other, we can only re-discover what we had already known about. On a journey or hike through the mountains, we are re-discovering what we have heard talked about, seen a brochure about, seen photos from, seen a map of. Plato’s paradox of learning occurs anew: if you know what you are looking for, you will only find what you sought, but if you don’t know what you are looking for, you won’t recognize it when you come across it.

The Pākehā legacy of Western scientific thought combined with a history of settler colonialism has characterized the New Zealand landscape as something to be mapped, charted, exploited. The proliferation of digital technologies and its accompanying access to records, reviews, maps, and GPS signals make it difficult for one to depart on a journey that unfolds as its own process. Planning the act of walking from a projective, totalizing point of view transforms that bodily experience into a line on a map. “Itself visible, [the line] has the effect of making invisible the operation that made it possible”, writes Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life. Fixations on product, the visible outcome or the projective trajectory, “constitute procedures for forgetting. The trace left behind is substituted for the practice."4 Embodied knowledge, tactile apprehension and kinaesthetic encounters are appropriated into a network of commodifiable information.

A pilgrimage is a kinetic ritual, and like all spiritual activities, it is inward looking. It promises to be the cure to a tumultuous psyche, the involuntary convulsions of emotions, and the ailments of an impermanent body. The passage from routines of daily social life towards the dwelling-places of the divine makes the activity a liminoid phenomenon and a subversive rite of passage. While journeying toward the divine, a pilgrim is united temporarily with other strangers in a mobile community of suffering bodies. Ultimately, pilgrimage is an anti-structure. One does not need any special qualification, authority, equipment or specialized knowledge to embody the expression of her religion. At the heart of the pilgrimage are laypeople with an ardent desire to create a shift in their physical, psychological and spiritual state.

About the Author

Balamohan Shingade is an independent writer and Indian classical musician based in Auckland. He is also the inaugural Manager/Curator of Malcolm Smith Gallery, a new contemporary art space for Auckland's Eastern Suburbs.

-

1.

Ruth Watson and James Wylie, Expanded Map (Auckland: RM Gallery, 2013), 5.

-

2.

I have not yet looked into the history of Māori pilgrimage, and its imminent possibility.

-

3.

Norman K. Denzin, “Indians in the Park.” Qualitative Research Vol 5(1) (2009): 14-15.

-

4.

Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 97.