Exhibition Essays

Rakau Matarau

June 2013

A nod to the past: Atua, transformer and the kaupapa of Reweti Arapere

Sian van Dyk

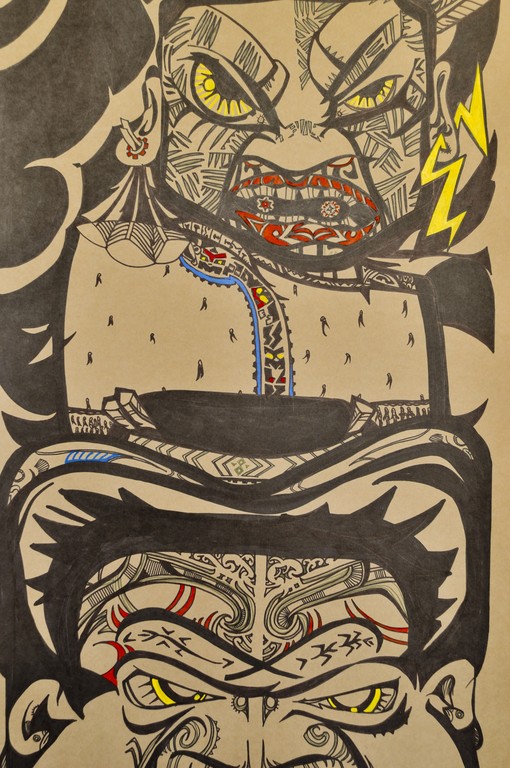

When you first walk into Rakau Matarau, you are welcomed by what appears to be a posse of larger than life toys. Constructed in cardboard, these sculptures are surrounded by two dimensional paper panels of figures, which line the walls of Enjoy Gallery. Drawn by hand, they resemble something you might see outside on the buildings of Cuba Street. If you take a moment you may also notice these artworks mimic aspects of customary whakairo, but bear a myriad of curiously juxtaposed symbols; from baseball caps and basketball sneakers, to ta moko: traditionally carved weapons and animals. This conglomeration of historical and contemporary symbols by Reweti Arapere seem as if they are in conversation with each other, and anyone who takes the time to interact with them. Each work is titled in te reo, revealing a clue to their full story. Arapere’s use of language is not the kind that can be looked up in a dictionary, and to date there has been very little written about his work which has developed a somewhat enigmatic quality despite its clear-cut graphic nature. To learn more, I took the opportunity to go to Arapere’s talk with Hemi Macgregor about the Kaupapa behind Rakau Matarau; to hear about the personal significance of these symbols and text to the artist.

It was clear that this korero was between two artists who are firmly grounded in Te Ao Māori. The stories that were told enveloped Arapere’s mahi, and were laden with cosmological narratives including aspects from the artist’s own whakapapa, something which is very personal and cannot be communicated wholly in an essay. What did surface from their discussion and is a useful point of reference for Arapere’s work is the term haerenga, or journey.1 This idea, that Arapere’s art practice is part of a collective journey is evident in his visual and conceptual nod to those who have walked before him. Like them, his kaupapa is to preserve his culture and his inheritance. This essay explores three steps in Aparere’s own haerenga to achieve his kaupapa; his use of te reo, what he has learnt from his tūpuna and mentors, and how these two components are reflected in his personal response to a shift in thinking in Aotearoa during the nineteenth century: a shift that continues to effect contemporary Māori art.

The first step in Arapere’s haerenga, his language, has been a part of his life since he was a child. After attending Kōhanga Reo, he became a first generation Kura Kaupapa tamariki, and treasures his language as a taonga by speaking it, using it in the written form in his mahi and celebrating its revitalisation. This is why he names his work so thoughtfully; “there is a lot to say in a title. Having a Māori title allows me to work in a medium that bests suits my thinking’’.2 Growing up as a bilingual child I can relate to the frustration of trying to translate a word that does not exist in English. Like Arapere’s language, mine too is bound geographically, grounded in one country, so the renaissance of te reo and its important role in keeping Māori culture alive is something I have been drawn to for many years. As I have learnt more about the intricacies of te reo I have found a timeless beauty in this language; for instance that the contemporary meaning of a word changes when considered within a historical or mythical context. Arapere’s use of te reo implies that the knowledge of such associations are like keys needed to unlock particular aspects of his work. Hence, when he is asked about the language he uses, he does not translate words into English, but tells you a set of stories instead.

An example of this is the title of this exhibition Rakau Matarau; when asked to discuss it, Arapere breaks up the various components of words and rearranges them to trigger a set of associations. Arapere’s use of rakau references the coupling of the words mau rakau. When combined, they mean to be armed or to wield weapons. He unpacks their relevance to his work by describing a scene of young men wanting to do the haka and pūkana without knowing what these culturally significant acts mean. His use of the word mata references the housing and passing on of knowledge and translates to mean head, because this is where mātauranga enters in through the eyes and the ears, and out through the mouth. Rau can be interpreted as multiples of things, lines, patterns and the act of drawing. Together rakau and mata represent the artist’s acknowledgement of the past, and that it is essential to understand where you come from to keep your culture alive, even if at times this can be a battle, both collective and individual. Rau emphasises that he has chosen to explore these elements with a multitude of visual and conceptual references, both historical and contemporary.

The second step of Arapere’s haerenga began when, as a teenager, he was seduced by the world of the graffiti artist Seen in the 1983 documentary Style Wars. As an adult and informed artist, Arapere developed a greater understanding of the political agendas surrounding ownership, and consequentially he also gained a broader appreciation of street art. He felt a powerful sense that no one could ‘own’ this art form, which often appeared anonymously overnight on the walls of buildings, and could disappear again just as quickly. In conjunction to this contemporary aesthetic that a twenty-first century audience is likely to recognise in Arapere’s work, there is also a reflection, as if through a looking glass, to late nineteenth century Aotearoa. This can be seen in his interpretation of customary whakairo and figurative symbols used in the decoration of meeting houses during that period.

For Māori, the conclusion of the land wars was a time of particularly “intense political and religious realignment, as various tribal groupings sought to establish their historical identity and to come to terms with indiscriminate land confiscations, the activities of the Māori land court, and the unpredictable actions of a series of European governments”.3 Consistently, before and after this period Māori have decorated their wharenui as a signifier of their collective identity. However, with the cultural uprooting that occurred there was a shift away from customary carving which once reflected the identity of iwi who owned these wharenui. Instead, what began to manifest was the practice of figurative painting. This sparked a significant change in thinking for Māori; moving away from the customary abstract signifiers which released historical knowledge, towards the individual expression of that knowledge. This involved recreating the narratives present in carvings in a more recognisable fashion and medium so that they would not be lost.

While customary signifiers and street art may appear worlds apart, they are both forms of visual culture which naturally change with the passing of time. Those who choose to undertake a visual art practice also need to move with changing cultures if they want to communicate successfully. It is no coincidence that Māori practitioners who have inspired Arapere including Riwai Pakerau, Shane Cotton, Lionel Grant4 and Rangi Kipa; have all acknowledged the important shift in thinking which grew out of the development of figurative painting of wharenui. They all have a sound understanding of where they came from with a mission to communicate this in their own milieu, in their own unique way. Closer to home, Arapere also finds inspiration from a koroua in his iwi, Kelly Kereama, who was a local tohunga whakairo. After studying customary carving at the New Zealand Arts and Crafts Institute in Rotorua, Kereama strove to carve living ancestors in a contemporary fashion into the wharenui of his region, adapting what he had learnt for the mokopuna who were leaving their marae for other parts of the country and world. Kereama wanted to create whakairo that new generations could understand so that they could connect with their whakapapa when they returned.

During the third step of his haerenga, Arapere strives to find his own way to tell the stories of his people in a contemporary context for the generation that follows him. He achieves this in a way that relates strongly to his own wharenui. The artist’s use of materials for instance harks back to his iwi Raukawa; who looked to the teachings of Kingi Tawhiao, the second Māori King. Tawhiao wanted to empower Māori; teaching that even though great leaders and times had passed, people needed to learn to make do with what they had in the present if they wanted to continue to survive. A particular Whakatauki from Kingi Tawhiao which Arapere draws from reads:

Maku ano e hanga I taku nei whare Ko ngā poupou he Mahoe, he Patate, ko te tahuhu he Hinau. My whare will be constructed. The pillars are made of Mahoe and Patate and I will gather Hinau to build the stern post for this house.5

Mahoe, Papate and Hinau trees are all common, small and at first glance insignificant. In native forests they fill the gaps between more important trees like Totara, used for making waka. However, these common trees are traditionally used for their medicinal qualities and for food. Arapere elaborates on their significance by revealing that “they don’t taste that good, but they can sustain you… This is what men in battle ate to keep going”.6 Just like these trees, the materials he has chosen to use - paper, cardboard and markers, are common too. Most people have access to these materials and so if the impetus is there, they can potentially use them to explore their own whakapapa. Arapere admits that cardboard lacks the integrity of wood and maintains that he doesn’t want to take the sacredness out of whakairo. However, by embellishing and shaping this material with new life, he wants to create a place for Te Ao Māori to be understood by a contemporary audience.

A significant component of the figurative symbolism Arapere uses as part of this embellishment is his graphic representation of animals, particularly mokomoko, ruru, tuna and huia which all appear regularly in his work. They embody principle themes explored in this essay; specifically the concepts of haerenga, gaining knowledge, looking to those who have passed to understand the future, and adapting to survive. Arapere’s use of mokomoko, or lizards, plays with the literal meaning of the word moko, which can be tattooing that illustrates the bearer’s whakapapa, as well as a reference to mokopuna, carrying on a line visually and literally. The ruru, or owl, is respected for its association with the night, which is treated with a certain wariness and is also related to death in Māori folklore. In Arapere’s mahi, ruru appear in the forms of the eyes of kuia, large and round. This visual technique of the Tainui Te Mōtu style that the artist uses honours the knowledge accumulated by kuia and, acknowledges that they are closer to the darkness at the end of life. Kuia also call karanga; summoning those who have been before to protect those who still walk the earth. The appearance of tuna, or eel, relates to the animal changing shape from big and fat to lean as it prepares for its migration out to sea to spawn, a journey that requires adaption and is essential to survive. Huia are a key component in Kaupapa Māori, and are an early and common figurative symbol in late nineteenth century meeting houses, appearing on the back wall of Arapere’s own wharenui – Te Tikanga ki Tokorangi. Huia were said to mate for life and epitomise morals for people to live by, embodying complimentary components such as working together, masculinity and femininity, life and death, and embracing the old and the new.

Towards the end of the artists’ korero, Claudia Arozqueta, Enjoy Gallery’s curator, remarked that Rakau Matarau had been a particular hit with school kids from around the lower North Island. Coincidently, I was lucky enough to be visiting Rakau Matarau myself during such a visit. It was a warming experience to see the kids’ eyes light up when they entered the Gallery; they were comfortable around these figures - unwary of the environment created by them as they interacted with the sculpture. Arozqueta also commented that the most common question asked about Arapere’s work was “are they transformers?” Upon hearing this, Arapere gave a knowing, wistful smile and admitted to wanting to make his own transformer sculptures, going on to explain that transformers originally came from ancient Japanese samurai. Knowing this, I am struck with a sense of awe and recognition, that without being told, there was something these children understood about what they saw. They picked up on the purposeful connections the artist made between ancient stories and contemporary pop culture. Like samurai and atua, these works have a certain mana. They are recreated in human-like forms so that we can relate to them, but are not quite human and so embody mystery and reverence.

Considering the artists various influences, are these works atua from cosmological narratives: constructed to teach their descendants about morals and tikanga, or, are they recreations of pop culture inspired super heroes: who can adapt to any situation thrown at them, their arms raised in a challenge? The answer is Ae. Yes. These art works are all of these things, created by Arapere to pay respect to those who have been before him, and to continue the haerenga of his tūpuna in a way that will ensure that his own mokopuna will feel empowered and excited to do exactly the same when their time comes.

-

1.

Hemi Macgregor, in conversation with Arapere in a public programme for the exhibition Rakau Matarau at Enjoy Gallery, 8 June 2013.

-

2.

Reweti Arapere, in conversation with Hemi Macgregor in a public programme for the exhibition Rakau Matarau at Enjoy Gallery, 8 June 2013.

-

3.

Roger Neich, Painted Histories – Early Maori Figurative painting. Auckland University Press, 1994, p. 2.

-

4.

Shane Cotton and Lionel Grant as well as Robert Jahnke, who is the head of school of Te Pūtahi ā Toi, The School of Māori Studies where Arapere gained his masters; all belonged to a collective of contemporary Māori artists published in a book called Mataora, a seminal text on contemporary Māori art in the 1990’s and also a big influence on Arapere.

-

5.

Reweti Arapere, in email to Sian van Dyk, 14 June 2013.

-

6.

Reweti Arapere, in conversation with Hemi Macgregor in a public programme for the exhibition Rakau Matarau at Enjoy Gallery, 8 June 2013.