Exhibition Essays

Not From Fractions, But Tides

August 2023

Not From Fractions, But Tides

Brooke Pou

Motherland Homeland is the exhibition that welcomes me to Enjoy, where I have just been hired as curator. Unfortunately, I could not make it to the opening as I was at a wānanga in Tauranga. Fortunately, one of the featured artists—Emily Parr—was at the same wānanga. We are whanaunga through our shared Tauranga Moana tūpuna and are both looking to reconnect with the iwi and whenua that were taken from us through colonisation, war, confiscation and time. At Otawhiwhi marae we learn an important waiata of Ngāi Te Rangi, which includes the line “He Iwi mokemoke manene e, he mōkai nanakia he tūtūa.” 1 This waiata describes the history of our iwi as one that endured being landless and lost before finally settling in Tauranga Moana. Here, our tūpuna found their tūrangawaewae. Centuries later, theft made some of us a wandering people once again. It is through this lens that I view Motherland Homeland, a group show curated by Bonni Luafutu-Tamati of five Moana artists living and working in Aotearoa.

Motherland Homeland, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Emily Parr, ‘Uhila Moe Langi Nai, Siliga David Setoga, Pilimilose Manu and Monica Paterson are all of the Moana. Though there is a great amount of interconnection and shared history between the many Islands that make up Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, there is a lot of diversity too. Acclaimed Moana writer Epeli Hau’ofa once said that

"...our diversity is necessary for the struggle against the homogenising forces of the global juggernaut. It is even more necessary for those of us who must focus on strengthening their ancestral cultures in their struggles against seemingly overwhelming forces, to regain their lost sovereignty." 2

Living in the diaspora and working in the art industry is a peculiar experience. Museum, gallery and university collections have acquired many taonga via nefarious and respectable means. These places have historically been controlled by Pākehā men with little understanding of the cultures that the objects in their collection storerooms came from. Spaces like Enjoy are one of the seemingly overwhelming forces where Moana artists such as those in this exhibition have fought to regain sovereignty.

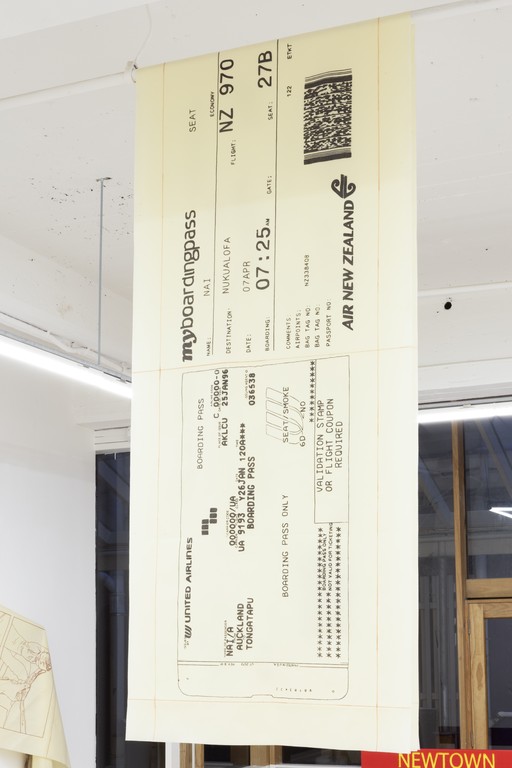

'Uhila Moe Langi Nai, They were always returning home, 2023, pepa koka’anga (vylene paper), screen printed ink, brown charcoal. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

They were always returning home is suspended in the centre of Enjoy’s main gallery. Its creator, ‘Uhila Moe Langi Nai, is known for her exploration of koloa, ngatu mo e kupesi. The work is a large scale vylene version of Nai’s 1996 boarding pass to Nuku’alofa, a statement to all who enter the exhibition that although Nai lives and works in Tāmaki Makaurau, her homeland will always be Tonga, where she was taught by her Nena to create ngatu.3 The arduous process is women's work, for “It is women who have governed this tradition historically which has served as a mechanism for women to define themselves, but more importantly to define aspects of Tongan cultural identity.” 4 This identity is expanding, much like the artist’s practice. In Nai's work Nima Poto, we get a glimpse into the customary way of making ngatu, a process that requires immense physicality. With knowledge from her tūpuna, Nai continues their legacy by experimenting with materials and displaying her artwork in galleries across the motu. As Lana Lopesi notes in False Divides, “It is important to remember that while Moana cultures are firmly rooted in customary practices, they are also active participants in the contemporary world.” 5 Nai honours her tūpuna by continuing to uphold the skills she has learned from them while sharing the fruit of their collective labour with us.

Siliga David Setoga, Village Sign—Porirua, 2023, acrylic on pine. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

For this iteration of Motherland Homeland, Siliga David Setoga has produced three sign posts relevant to diaspora communities living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. They are an eye-catching bright red with yellow lettering inspired by village signs in Sāmoa. As a lifelong Wellingtonian, Newtown, Porirua and Lower Hutt are all familiar—I have worked in two of these locations and had whānau living in the other. Many are aware that recent efforts to ‘regenerate’ Porirua East have been denounced by locals who form groups like Housing Action Porirua to fight for their community. Gentrification during a period of severe housing need has had disastrous effects on low income residents and reflects this country’s history of securing land by dispossessing mana whenua. The involuntary nature of gentrification brings to mind Lopesi’s suggestion that migration of tangata Moana to Aotearoa has been influenced by imperialism. Lopesi notes that “contemporary Moana existence is so entangled within the imperial project” 6 and questions “how much freedom is really afforded, when our migratory paths are predetermined by colonisation.” 7 These are important points to keep in mind while walking through Motherland Homeland. Despite the fact that imperial interests in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa are still a contentious issue, Setoga’s posts show that the influence that Moana peoples living in Newtown, Porirua and Lower Hutt have had in their communities remains strong.

Pilimilose Manu, Sola and Dee, 2022, digital photgraphic print, Hahnemühle Photo Rag paper. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

The many cultures in the Moana were of great interest to the few Europeans who had the means to travel here centuries ago, where visitors were captivated by the people they encountered. Our reputation as a paradise full of noble savages and dusky maidens was fabricated in the recollections, journals and drawings from those aboard the ships of ‘discovery’ in the eighteenth century, but affirmed by photographic proof of the early twentieth century.8 The entrepreneurial response to capitalise on brown bodies resulted in widespread distribution of manufactured images in the form of exotic postcards. If a choice of postcard tells you something about the people who make, send and receive them,9 then I wonder about each of Pilimolose Manu’s seven black and white photographs. Art historical references run through the series. Daz and Ben are a cheeky allusion to The Creation of Adam, with one young man in casual dress reclining in his backyard while another wears his Sunday Best, reaching out with a Bible in hand. The wāhine pictured in Viva recreate Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in suburbia, though this Venus stands tall in an iconic clamshell pool with a beaming smile on her face. Manu gives us glimpses into his subjects’ homes, their relationships with each other and their cultures. He is clearly deeply rooted to his community in Tāmaki Makaurau, where he utilises his connections to take these images. Unlike the various postcard photographers, I see the connection between photographer and subject in Manu’s series.

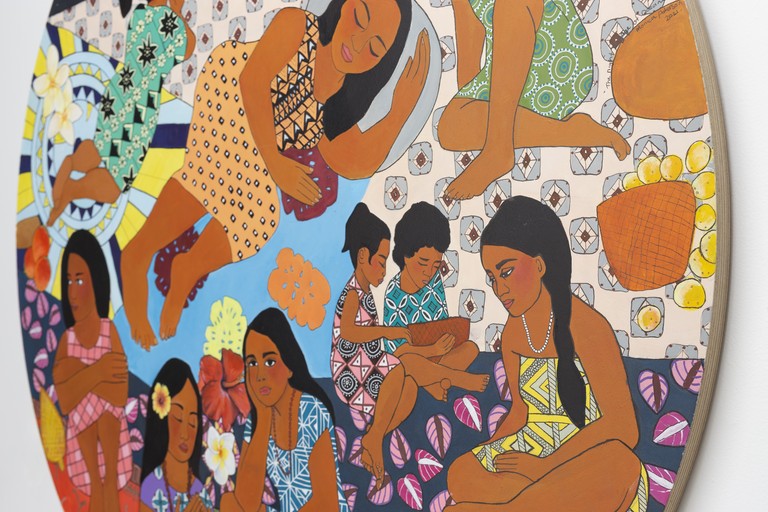

Monica Paterson, Night Voyage of Oceania, 2020, acrylic on board (detail). Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Monica Paterson’s paintings and prints are placed sporadically around the gallery and reading room. They are made up of Moana motifs and scenes of serenity, demonstrating the artist’s commitment to lovingly depicting her heritage. Their shapes, patterns and colours should make them seem chaotic, yet the tranquillity of Paterson’s figures puts me at ease. After all, the wāhine in these works are sleeping, stargazing, dancing and praying. Everyday activities have been lovingly crafted into artworks that chronicle ordinary things women throughout the Moana have been doing for centuries. Night Voyage of Oceania features ten such figures. The woman in the centre has peacefully fallen asleep, while others sit and lay around her, connected through their culture if not their actions in this painting. Sāmoan scholars have written about the concept of vā for over two decades and for the sake of simplicity the idea is often reduced to ‘the space between.’ The star-filled sky in Night Voyage of Oceania makes me think of the vā between my ancestors who used it to navigate the world's largest ocean and I.

Emily Parr, Moana Calling Me Home, 2020, moving image work in six parts, total length 1 hour, 11 minutes and 39 seconds. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

“I am cloaked in the mauli of my ancestors, woven from their stories of migration, longing and belonging, island entanglements, with Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa always at the heart.” 10

While I see the vā in Paterson’s artwork, I feel it in Emily Parr’s. In six segments, Emily crafts a narrative of her whakapapa, weaving in and out of Sāmoa, Tonga and Tauranga Moana. Moana Calling Me Home collapses the space between artist and audience. Extensive research in different museum archives, libraries and countries allow Emily to take us on a haerenga where we learn about the artists whānau with her. During an artist talk that I facilitated at Enjoy, I thanked Emily for sharing her considerable research with us. There are things in this film that I would not know about our tūpuna if not for her dedication to piecing together stories of our heritage and I cannot adequately describe what it means to me that she has constructed this work of art. In part five: Tūrangawaewae, Emily details the history of our tūpuna Ruawahine of Ngāi Tukairangi and John Lees Faulkner. Their story is a common one in which a European settler chooses to marry a Māori woman of great mana, utilising her hapū and iwi connections while also denigrating her culture. Emily voices diary entries written by primary sources who describe Faulkner calling out “Now children, let me hear no Māori” 11 when they dared to speak their mother tongue. Emily proudly states that the children defied their father, but I wonder how many generations it took for us to lose the language. After the Battle of Pukehinahina and subsequent confiscation of Ōtūmoetai Pā in 1864, some of Ruawahine and John’s children migrated away from Tauranga. Four generations later, my grandmother ended up in Whangārei, where she married a Ngāpuhi man whose whānau had a disparate experience. Each of these actions have forged the person I am today, someone “made up not by fractions, but by the tides of the Moana.” 12

Motherland Homeland, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

-

1.

Ngāi Te Rangi, “Nā Te Rangihouhiri,” we are a lonely iwi, a wandering people

-

2.

Epeli Hau’ofa, “The Ocean in Us” in Understanding Oceania: Celebrating the University of the South Pacific and Its Collaboration with The Australian National University, ed. Stewart Firth and Vijay Naidu, (Canberra: ANU Press, 2019), 343, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvk8vzcb.21.

-

3.

“‘Uhila Moe Langi Nai,” The Arts Foundation Te Timu Toi, 4 May 2023, https://www.thearts.co.nz/artists/uhila-nai.

-

4.

Mele'ana K. ‘Akolo, “A feminist interpretation of women's work with Koloa in the Tongan community,” IdeaFest: Interdisciplinary Journal of Creative Works and Research from Humboldt State University 2, 2 (2018): 12, https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/etd/26.

-

5.

Lana Lopesi, False Divides (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2018), 60.

-

6.

Lopesi, False Divides, 66.

-

7.

Lopesi, False Divides, 67.

-

8.

Alan Beukers, Exotic Postcards: The Lure of Distant Lands (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2007), 11.

-

9.

Beukers, Exotic Postcards, 12.

-

10.

Emily Parr, Moana Calling Me Home, 2020, moving image work in six parts, total length 1 hour, 11 minutes and 39 seconds, part two: Oli Ula.

-

11.

Parr, Moana Calling Me Home, part five: Tūrangawaewae.

-

12.

Parr, Moana Calling Me Home, part five: Tūrangawaewae.