Exhibition Essays

walking forwards backwards

September 2016

Many threads

Simon Palenski

A few years ago, Annie, some friends and I visited a friend’s sheep station in Central Otago near Kingston. We stayed during summer and I remember how on the last day, as we were packing my car to drive back to Christchurch, our friend’s dad gave Annie an armful of merino wool. Later, Annie mentioned that she had started spinning her own thread on her granny Noelie’s old spinning wheel—so maybe this happened around the time of our trip south. I know she was quite taken by our friend’s station; the sheepdogs, fleeces and lamb chops.

I was also around last year when Annie and her partner Dave had an exhibition titled International Foodcourt/Global Classic at The Physics Room, Christchurch.1 Here, I got to see Annie’s handwoven works with designs based on ordinary tea towels. They hung on the walls of the gallery and over steel bars and tables around the room.

I wasn’t able to see Annie’s exhibition walking forwards backwards (2016) at Enjoy. Because I missed it, Annie posted me an envelope filled with palm-sized samples of wool and thread used to make her textiles in the exhibition. With these, she wrote notes describing where each piece was from, what loom she used to weave with, sometimes a sketch of the woven textile and instructions to pay attention to the feel, the scent (“organic like silage”) or even that I needed to hold it up to light to see the fibres.

Annie Mackenzie, walking forwards backwards (detail), 2016. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

I recognise some of the samples in the exhibition photos. A skein of charcoal grey Romney yarn that was used by Annie to make a woollen blanket; another clump of cream and gold linen thread to weave the long curtain; and some black, grey and black/white plied yarn woven into a piece that for Annie is like an old fisherman's net. She also said that the colour reminds her of television static. Helpfully, Annie’s notes often describe less visible details: “Linen – very old given to me by Lynne of Addington … Made on ‘Ford’s of Nelson’ loom – Countermarch at Trish Amour’s house in Wadestown”, “Grown by Janice Winter of Canterbury”, “Commercial weavers cotton German made?” Sometimes, they hint at details that are lost for now. With a small mass of sea green linen, she writes “from an unknown woman at Canterbury Spinners & Weavers Guild I wish I could remember her!” With the charcoal yarn, she notes that the intertwined pale grey threads might be the best/most precise hand spinning she has done. As I hold it up to look, I can see how neatly the two threads of yarn are wound.

Along with these notes, there are the transcribed conversations Annie had with weavers of another generation, her teachers Brigit Howitt and Robyn Parker, Lyndsay Fenwick from Christchurch and Philippa Vine and Nola Fournier who were teachers during the 1980s at the weaving school in Nelson.1 In the exhibition, the transcripts were printed on eight metre long rolls of paper (about an hour of talking each) that spooled from the top of the wall and curled up on to the floor. Together, they record a common past, a halcyon time between the late 1960s and mid 1980s when many women in New Zealand were involved in weaving and spinning and, for the most part, taught and learnt from each other. In one conversation, Brigit remembers how in Wellington alone there were over two hundred members of the Port Nicholson Weavers—and seven or eight hundred in the wider Wellington region. Concurrent with this was a sustained revival of Māori fibre arts with weavers such as Diggeress Te Kanawa teaching traditional methods of whatu and raranga to many women, and the formation of weaving schools such as Te Whare Raranga in Rotorua. Te Kanawa would later co-found Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa, a national Māori weavers collective.3

This was also a time when woven textiles started to be taken seriously in the art world, and were exhibited and entered the collections of galleries and museums around the country. Despite this, at least in the dominant New Zealand art history, weaving and spinning have often been considered as a part of domestic life, and as a result been trivialised and left out. This is noted by the historian Heather Nicholson in The Loving Stitch (1998), her history of knitting, weaving and spinning among Pākehā in New Zealand.4 Nicholson describes how fibre practices were denounced, ignored or ridiculed by critics, and, further, that their histories are in danger of being lost without a trace, due to garments, patterns and samples being left in op shop bins or deliberately unravelled and re-knitted. In their conversation with Annie, Brigit and Robyn recall how they have no idea where the enormous, wall-sized works they made for corporate commissions have gone, and Philippa and Nola talk about how so many valuable looms were sold, taken away and lost.

Annie Mackenzie, walking forwards backwards, 2016. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

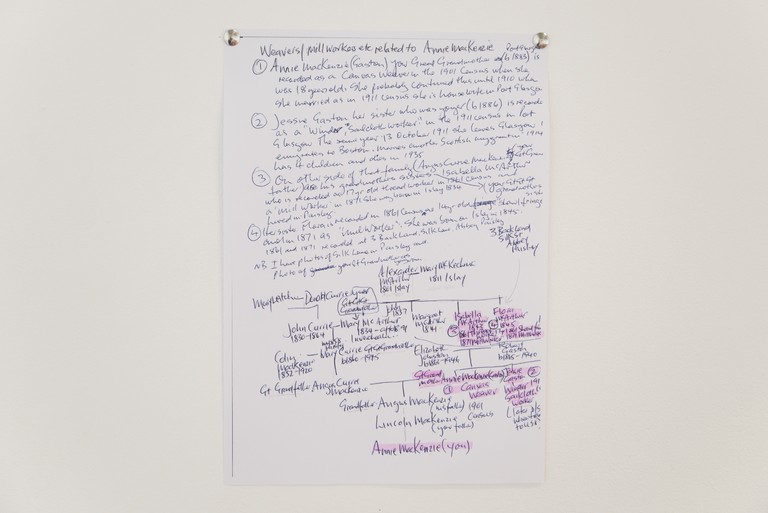

Another document in the exhibition is Annie’s family tree, handwritten by her auntie Helen. Pinned up on the gallery wall, all the weavers in her family (two to three generations back) are highlighted in pink. One of these weavers was Annie’s great-grandmother who was a canvas weaver in Scotland during the industrial revolution and whose name was also Annie Mackenzie. Links and stories like this seem to lend themselves to being expressed through fibre and textiles. The basic techniques Annie’s great-grandmother used are likely unchanged from those Annie uses today, and although Brigit and Robyn talk about how they were mostly self-taught, they both recognise how they were attached to a history and a tradition.

In the same way histories and stories can be expressively told through textiles, they can also be unravelled and forgotten. Like the lost details in Annie’s notes, the lineage of the patterns and designs of Annie’s tea towels—although instantly recognisable from our own kitchens—have been obscured through mass production and consumption. Recording information on paper does not necessarily guarantee its preservation, there are too many examples in the past of carefully documented collective memories going up in flames. History depends much more often on happenstance, luck and what is often seen as ephemeral: the everyday (like tea towels, blankets, curtains and scarves, but also people’s thoughts and feelings) and the spoken, remembered and passed on.

In walking forwards backwards, Annie has allowed women’s voices to speak for themselves through her textiles and texts. Together, the written documents and woven material start to feel remarkably similar. Both capture and preserve the story of weaving in Annie’s life, as well as in the lives of the women she talks to. These lives form a history, one based on how they felt and what they thought, understood, remembered, or believed in. They show how history is not a seamless document; even when it is closely researched, seams and inconsistencies will spill and split.

-

1.

Annie Mackenzie and Dave Marshal, International Foodcourt/Global Classic, The Physics Room, 4 June – 9 July 2016, http://www.physicsroom.org.nz/exhibitions/international-foodcourtglobal-classic.

-

2.

Read interviews between Annie and these weavers online:

Annie Mackenzie Talks To Brigit Howitt & Robyn Parker

Pauatahanui, 26 August 2016Annie Mackenzie Talks To Lyndsay Fenwick

Christchurch, 15 July 2016Annie Mackenzie Talks To Philippa Vine & Nola Fournier

Nelson, 22 July 2016Typeset by Ella Sutherland.

-

3.

Kahutoi Te Kanawa, "Māori weaving and tukutuku – te raranga me te whatu - Revival of Māori fibre work", Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/maori-weaving-and-tukutuku-te-raranga-me-te-whatu/page-5.

-

4.

Heather Nicholson, The Loving Stitch: A History of Knitting and Spinning in New Zealand, (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1998).