Exhibition Essays

Enjoy Gallery Catalogue 2006

December 2006

-

Dear Reader,

Paula Booker -

Good Willing

Eve Armstrong, Rachel O’Neill -

Rhythm is best considered fractally...

Pippin Barr -

The Lucky Sod

Melanie Oliver -

Treading the Boards

Andrea Bell -

Old Money

Jessica Reid -

Sex and Agriculture

Jessica Reid -

Mowing down the puppies, and other suburban stories

Sandy Gibbs -

Call & Response

Louise Menzies -

The Reconstruction and Retrieval of Enjoy Public Art Gallery

Michael Havell -

Becoming Animal: Essays on Aura 2006

Anna Sanderson -

Looking Up

Louise Menzies -

Powder Pink and Sky Blue Dreamland

Rob Garrett -

Action Buckets

Melanie Oliver -

Whose Street is it Anyway?

Melanie Oliver -

Can you hold the line please?

Melanie Oliver -

Ghetto Gospel

Thomasin Sleigh -

Hot Air

Paula Booker -

Statement

Kaleb Bennett -

Amigos

Paula Booker -

S.O.S. Save Us From Ourselves

Mark Williams -

Time warp

Thomasin Sleigh -

Every Now, & Then

Amy Howden-Chapman

Looking Up

Louise Menzies

“Is there an art that can be greater than the beauty of the sky?” Yoko Ono1

Discussions of the weather form some of our most rudimentary encounters. As a perfectly neutral point of conversation, we are able to avoid the personal, while sharing – in the most mundane of ways – our understanding of the world.

What a relief it is to be able to state my dismay at the pending rain to someone I do not know as I wait to ride the bus. As these encounters make obvious, weather generates language more efficiently than it does knowledge – for while weather is always with us, its exact properties are not always clear. Douglas Bagnall’s online project Cloud Shape Classifier uses the general subject matter of weather to tap into our recognition of clouds as the shapes and colours of meteorology, translating visually the temperatures and winds that shape our atmospheric experiences.

History has shown clouds to be elusive in our attempts to come to terms with an accurate set of descriptors for their many vaporous forms. It was not until the early nineteenth century that at last a full system for their classification was determined by the British scientist Luke Howard. Amidst the heyday of Enlightenment taxonomy, Howard’s terms of cirrus, stratus, cumulus and nimbus provided a welcomed understanding for the scientific and artistic communities at the time.

Studies by the English landscape painter John Constable, of the sky above Hampstead Heath painted over the summer months of 1821 – 22, embody both the awe and curiosity for the natural world so prevalent in Europe during this period. In their attempt to capture the science of these forms equally with the emotions of wonder, turmoil and change, one can see in these small paintings an almost fierce attempt to capture the world as it might exist.

As it happened, Te Papa Tongarewa was host to the touring survey exhibition John Constable: Impressions of Land, Sea and Sky, concurrent to Enjoy’s presentation of Bagnall’s Cloud Shape Classifer.2 This coincidence usefully provided a background for the way in which the Cloud Shape Classifier appeals to a tradition of landscape painting through its mimicking of our natural world and use of customs familiar to us from the wider history of representation. However, rather than Howard’s orderly observations – as illustrated so finely by figures such as Constable – Bagnall offers us an open classifying system, which answers to taste in place of reason.

The history of taste is almost as old as the history of weather; and here we can usefully compare a series of watercolors depicting a historical English landscape setting with digital snapshots of the air above Wellington – more precisely the sky out of the window of a small gallery on upper Cuba St – as a way to reflect on the very human act of showing the world back to ourselves. From landscape painting to Ono’s Sky T.V. to online weather cams, the Cloud Shape Classifier continues this idea of mediating our experience of the natural world.

In many ways the classifier is like a small brain. A basic model of artificial intelligence works to make sense of our aesthetic decisions that, as we develop it to our own taste, proffers images of clouds for us to enjoy. Through a careful mathematical scheme, the classifier deciphers and then illustrates our taste for us. Via the computer program Bagnall has built we are given the tools to create our own archive of aesthetic choices. This trained tastemaker narrows our selections over time to arrive at an individually determined visual scheme and, similar to the processes of adaptation we understand species to undergo within the concept of Natural Selection, each classifier evolves over time toward its own entity.

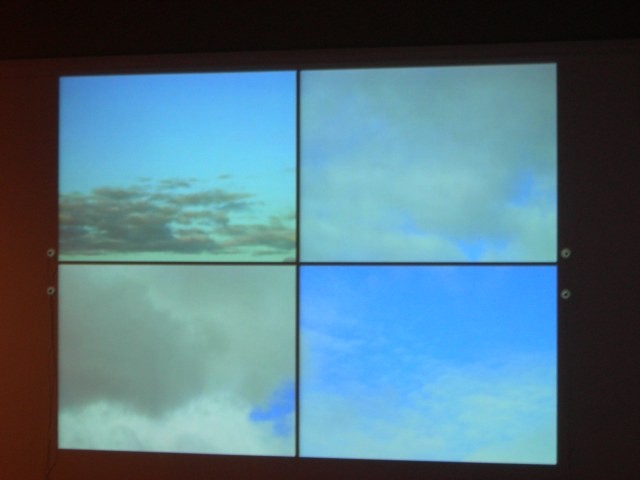

For Enjoy, a projection was focused on the wall showing a version of the online public classifier. Split into four, the projection refreshed itself every two minutes as more data was captured from the sky through a digital camera placed upwards at the window. Next to each image on the wall was a small button that when pressed constituted a vote, and fed back to the classifier as if this button had been clicked online. The public classifier is fascinating in its confusion. Here is a classifier endlessly grappling with the different decisions of its many contributors, muddled and left dangling for a sense of direction after the numorous and varied votes it receives daily - as preferences for dusky pink-capped cumulus fight it out with grey and melancholy swirling masses of air and light.

As a result of its own means, the Internet is full of sites that show off the ability of the World Wide Web to harvest and analyze people’s judgments. These rating schemes include the useless yet compelling examples: Rate My Rack (www. ratemyrack.com, where visitors can view and rank images of breasts uploaded by women seeking a public rating of their own “racks”) and Hot or Not (www.hotornot.com, this is a tamer site where visitors are shown more portrait style home-photography of both sexes to assess).

At the other end of the spectrum are the more practical likes of Amazon’s “recommended” function, which compiles raw statistics with personally crafted lists to accurately suggest titles of relevance, through to the mass-posting heights of the open-source encyclopedia Wikipedia.

Where does this locate the Cloud Shape Classifier? As an art project? As something offering functionality? As both? Similar to other projects of Bagnall’s, the Cloud Shape Classifier works as art allowing us to consider the media space of technology together with aesthetics. Through the use of technology for romantic means the Cloud Shape Classifier opens up a multitude of relationships within an online environment, between the natural world and its reproductions, authorship and taste, accessibility and participation.