The Occasional Journal

Love Feminisms

November 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton -

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt -

Considering Merata Mita’s Legacy

Chloe Cull -

Armour. Armor. Amor. More.

Zoe Crook -

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo -

This mud body

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa -

CONVERSATION

Creek Waddington, Sian Torrington -

Bloody Women Artists

Ruth Green-Cole -

the blue between me and you

Jo Bragg -

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans -

A guide

Rachel O’Neill -

Gender and the ANZAC Biscuit

Lindsay Neill -

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa

A male peer once said performance art was only for those with ‘beautiful’ bodies. Beauty trends are always changing, yet the fashion and dance sectors have standardised a particular body type for women in public space. When New Zealand decided to jump on the Next Top Model bandwagon, it came under fire for initially turning away a contestant for being a size 12. The Next Top Model producer was reported as saying “it’s the reality of the business that sample sizes of clothes come in sizes 8 and 10 and the models have to be able to fit them.”1 These examples portray an ‘idealised public body’ and in doing so, define a Western standard of beauty; one which seems to correspond with contemporary art practices. Artists like Carolee Schneemann, Hanna Wilke and Cindy Sherman made important work about women’s experience, the female body and domesticity, yet they all fit comfortably within this societal framework of what size a performing body should be. Like the fashion and dance sectors there is a lack of diverse representation within the art landscape when it comes to the female form. This construction of a ‘beautiful performance body’ is contested by the performance practices of Polynesian artists Darcell Apelu, Yuki Kihara and D.A.N.C.E Art Club, whose diverse concerns, bodies and approaches to art making exemplify the growing community of Polynesian women enriching and diversifying contemporary performance.

Western notions of first, second, third wave or post feminism2 have little resonance with Polynesian cultures who are also fighting racial and class-based oppression. The liberal feminist idea of a universal women’s experience can be unrelatable for women from cultures who have been victim to colonisation. Across the Pacific, colonisation saw the aggressive introduction of Western religion, thought and conservatism changing our own gender roles and understanding of beauty. In Samoa, Papua New Guinea and parts of Melanesia women are tattooed; in Tonga they prefer you to be fo’i sino (a little bit heavier); and throughout the Pacific, our hair is big and our skin is dark. Moving into the diaspora it’s hard to place Pacific people in roles outside sport, where our naturally athletic bodies seem at home. We are often absent from mainstream presenting and broadcasting, except to fill typecasts on programmes like Shortland Street. Our body types are ‘other’ to the Western ‘idealised public body’.

The assertion of the female body through performance is not new, and neither is the Polynesian female body in contemporary art. An example of this is the Pacific Sisters collective, which operated throughout the 1990s and consisted of both Pacific and Maori artists, including Selina Forsyth, Niwhai Tupaea, Suzanne Tamaki, Rosanna Raymond, Feeonaa Wall, Ani O’Neill, Lisa Reihana, and Jaunnie Ilolahia. Influenced by their urban environment the sisters created performance works that were seen as ‘hybrid’, a mix of contemporary performance, theatre and dance with traditional forms of performance and ritual. “We get our inspiration from our immediate urban/media environment,” says one member; “We don’t stare at coconut trees – we stare at motorways”3 says another. Performing in public spaces is embedded within the various cultures of the Pacific; with every Island in Polynesia comes a very specific cache of songs and dances that are performed in front of friends, family and guests for different occasions such as birthdays, title ceremonies and funerals. When our ‘othered’ body enters the performance realm of art galleries and museums, our work enters a Euro-American art historical lexicon which has inscribed those bodies in particular ways as outlined in our introduction. Worldwide cultural practices differ so immensely from that of the dominant Euro-American psyche, and so non-European feminist visual languages are often contextualised as and limited to discussions of culture, colonisation or identity. Cuban-American performance artist Coco Fusco’s work is a great example of a lack of acknowledgement of the alternate positions already put forward by postcolonial feminisms.

![John Webber, Poedua [Poetua], daughter of Oreo, chief of Ulaietea, one of the Society Isles, 1785. Purchased 2010. Te Papa: 2010-0029-1.](/media/cache/3c/b9/3cb975fb665b2eeec7e651959e820e1d.jpg)

John Webber, Poedua [Poetua], daughter of Oreo, chief of Ulaietea, one of the Society Isles, 1785. Purchased 2010. Te Papa: 2010-0029-1.

Along with contemporary art institutions that have a history of being dominated by white male artists, the Western gaze within these institutions can also be problematic for Polynesian female performance artists as viewers are more than likely to have limited or no knowledge of Pacific ideologies, hindering in-depth readings of the work. The Polynesian female form has been coveted sexually by male European explorers since early encounters between the two. Over-sexualised and over-commercialised, we are still fighting against the early twentieth century labelling of the dusky maiden as a “loose” sexual object of desire. In the late seventeenth century, Euro-American audiences were introduced to representations of the Pacific body and landscape through painters such as John Webber, whose painting The Tahitian Princess Poedua, the daughter of Oreo, Chief of Ulaietea, one of the Society Isles (1785) depicts a young woman who has a white garment wrapped around her waist, while the top half of her body is bare. The painting is in the style of conventional neoclassic portraiture, yet Poedua’s adornments allude to a more exotic way of life as she clutches an item that looks like a fan in one hand and has a flower tucked behind her hair. Perhaps more famously in the nineteenth century, Paul Gauguin and other cultural producers also promoted the notions of the ‘noble savage’ and ‘dusky maiden’. The dusky maiden is sensual, bare breasted, alluring and submissive as she poses for Western viewing pleasure. These paintings were not made for Polynesian people to hang in their homes but for Europeans to consume. However, the consumption of this sexual icon is alive and thriving today especially in the form of tourism, when Google searching the phrase Polynesian Women will result in bikini clad (or even naked) women either on the beach or in a pool of water and adorned with flowers, which have been posted by both Polynesian and non Polynesians alike. Elsewhere, Polynesian women are criticised if they are large, or for having ‘loud’ laughter. This perception is often seen on social media platforms such as this comment from a thread titled Why are Maori/Polynesian women so disgusting and annoying:

“I been everywhere in NZ and I seen the same thing. They can’t even talk or try to talk properly nor dress and act like a lady, the thing that gets most to me is the way they laugh like they retarded or something. Every time I see one of em I feel like handing them a gym membership and some Thin Lizzy”.4

Darcell Apelu, New Zealand Axemen’s Association: Women’s Sub Committee - President, documentation of performance, August 2, 2014. Image courtesy of Peter Jennings © Artspace NZ

The contemporary Western gaze also promotes other forms of stereotyping, especially as Polynesian people excel on the sports field. In 2006 the Samoan Olympic discus thrower Beatrice Faumauina placed second in the New Zealand version of Dancing with the Stars, and in doing so, deconstructed the idea that her body was only successful in Olympic field events and not on prime television as a dancer. Darcell Apelu, like Faumauina, challenges the western concept of the Polynesian performing body. Apelu is a performance artist and athlete whose practice is often grouped with other Polynesian explorations of diaspora and identity. Often missing from discussions of Apelu’s work is the exploration of how her practice regularly critiques the representation and role of women within a Pacific framework. In the performance, New Zealand Axemen’s Association: Women’s Sub Committee President (2014), Apelu showcased her power and strength as she chopped a large block of wood in half in the main exhibition space of ARTSPACE NZ. For the average artist this would be no easy feat, but for Apelu—a New Zealand representative wood-chopper—the performance was a demonstration of power, and the audience became witness to her physical strength and endurance. Watching the performance, the audience seemed to be in awe—which, given using an axe with precision and skill is no easy feat, is fairly understandable. Perhaps another cause of such a reaction is the lack of representations in mainstream media of Pacific Islander women who play ‘masculine’ sports. Unless it’s the Olympics we don’t hear much about Valerie Adams or the women’s rugby team the Black Ferns; but we know we’re all likely to see the All Blacks in the New Zealand Herald tomorrow morning. Apelu’s emphasis on Western ideas of strength, rather than the female form, highlights possibilities for alternate Polynesian bodies while also challenging the audience’s perception of a Pacific Islander woman.

Apelu also challenged audiences who viewed her performance work Untitled (2013). Dressed in black, Apelu walked around the crowded exhibition space of St Paul St Gallery with a comb in her hand. Stopping in front of an audience member willing to engage with the work, she then brushed her long hair in front of them, as if using the audience member as a mirror. Through the performance, the artist dominated the gallery space, creating a shift in institutional power dynamics where—as one of the few Pacific Islanders in the space—she was the obvious minority. Each of the audience members Apelu encountered became ‘other’ to her Pacific gaze. As the audience, the imagery we witness is completely opposite to the classic colonial black velvet paintings of Charles McPhee and his Tahitian princesses. Instead of bare breasted dusky maidens the artist offered the audience her own truths, her hair long and frizzy, her body plus size, her gaze staunch not vulnerable and her breasts very intentionally covered. Unlike the flat 2D portraits Apelu is in your face real, especially in this particular performance. Polynesian bodies have a long history of being objectified and so Apelu’s decision to remain covered is not to be conservative, but an expression of protest, to refuse to partake in performing a role that is expected of her. In reclaiming her own representation, Apelu controls how she is presented, not the audience.

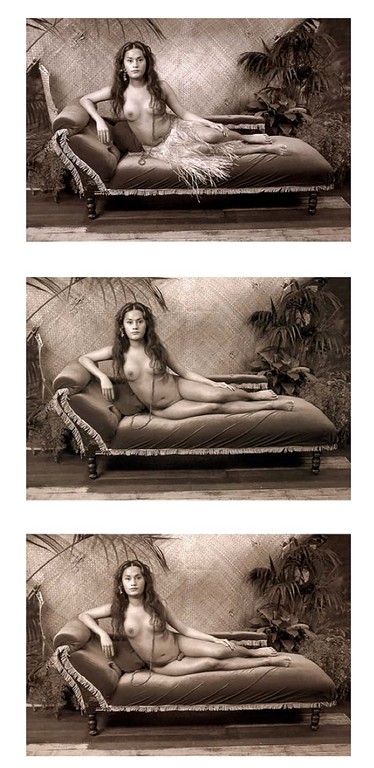

Amidst the world’s fascination with reality TV star Caitlyn Jenner’s transition, for over 20 years fa’afafine Yuki Kihara has been redefining the Polynesian woman. Multidisciplinary artist Kihara is Samoan born and of Japanese and Samoan descent. She identifies as fa’afafine, which in many ways can be seen as a non-binary gender and part of the structure of Samoan culture. Fa’afafine literally means ‘in the manner of a woman’. Being fa’afafine is foregrounded through her practice, and Kihara is conscious of sitting between genders, simultaneously occupying a place between ethnicity and gender, seamlessly and elegantly shooting out multiple lines of enquiry.

Kihara’s exploration of gender takes place through an enquiry and subversion of ethnographic photography. Interested in colonial depictions of Polynesian people, she reclaims this photographic space in her work and owns the Polynesian body before and behind the lens. In Fa’a Fafine: In a Manner of a Woman (2005), Kihara presents herself as a man, woman and fa’afafine, revealing her own identity as a shifting entity. Kihara is in complete control as both the subject and author of these depictions of her body. She skilfully addresses the misrepresentation of an indigenous society, moving away from a Eurocentric depiction of a Polynesian female body and reclaiming the photographic space as her own.

Yuki Kihara, Fa’afafine: in the manner of a woman, triptych, 2005. Image courtesy of the Artist and Milford Galleries Dunedin

Kihara further presents her body in female performance space as the character of Salome through the high ceremonial dance form Taualuga. The solo dance is usually performed by the chief’s daughter in a Samoan village on special occasions and is considered one of the more important art forms in Samoan culture. In the works Taualuga; The Last Dance (2006-2012), Siva in Motion (2012), and Galu Afi; Waves of Fire (2012), Kihara embodies the subject of Thomas Andrew’s photograph Samoan Half-Caste (1886). In a Victorian mourning dress, the artist dances the taualuga. Her seduction references the story of Salome from the New Testament who performed the ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’, which lead to the execution of John the Baptist. This work continues Kihara’s enquiry into the appropriation of colonial imagery as a way to investigate the past and the future.

D.A.N.C.E Art Club at the Guinness World Record Attempt during welcome, Artspace, 2014. Image courtesy of Janet Lilo

D.A.N.C.E (Distinguished All Night Community Entertainers) Art Club also expands perceived ideas of the Polynesian female body in performance spaces. D.A.N.C.E is made up of 4 members: Linda T. Tanoai, Ahilapalapa Rands, Vaimaila Urale and Chris Fitzgerald. Three of the four members are Polynesian women, and between them they can wear many labels: queer, straight, mothers, mixed race etc., but more importantly, they exemplify the complexity of the Pacific female. Their practice is based on manaakitanga and hospitality. Being hospitable across Polynesia is a way of being, it is an inherent component of life. Hospitality in a Pacific context is not seen as being compliant to role of the woman, but rather an empowering act of generating community and developing discussion.

D.A.N.C.E employ manaakitanga as a practice by hosting, talking and facilitating. In their project Crockpot (2014) at David Dale Gallery in Glasgow, Scotland, they sent five recipes including Samoan Sua Fa’i, which were made and served on consecutive nights to gallery visitors. Through the use of Samoan food and Pacific ways of hosting, D.A.N.C.E facilitated a unique exchange of culture in a Glasgow art space. These simple gestures of cooking and nurturing audiences are a reclamation of the role of the host. D.A.N.C.E’s practice sits within a long lineage of social practitioners, from Joseph Beuys to Rirkrit Tiranavija, but in terms of Polynesian female bodies engaging with social practice in New Zealand’s contemporary art spaces, what they are doing is new. By using key components of Polynesian cultural practices, D.A.N.C.E creates meaningful moments of exchange and engagement. Furthermore, they challenge a one-way gaze upon themselves—the ‘other’—by self-positioning themselves and requiring a relationship or exchange with the viewer.

The presence of Polynesian female bodies in performance is both a blackening of the performance space and a form of resistance. Pacific women in performance is not new, however in some ways their contribution has been written out of art history because they were not always recorded or commented on. Both within and outside of the art and Polynesian communities, practitioners like Leafa Wilson and Pacific Sisters have been the victims of this erasure from mainstream art history. Darcell Apelu, Yuki Kihara and D.A.N.C.E Art Club have become important contemporary examples of practitioners of feminism and thankfully are getting more recognition. Within each of their practices they renegotiate institutional spaces that are dominated by white males by creating a necessary counter conversation. Apelu, Kihara and D.A.N.C.E Art Club question perceptions of the exotic body, gender and ideas of domesticity in Polynesian culture and in doing so they redefine it.

About the authors

Lana Lopesi is a writer and practitioner based in Auckland, New Zealand. Specialising in arts criticism, Lana’s writing often focuses on Pacific and Social art practices and surrounding issues. Lana is the co-founder and editor for #500words, a website for critical discourse on art and culture.

Louisa Afoa is an Auckland based artist, her documentary style practice often reflects her surroundings. Through explorations using popular culture as a lens, she delves into ideas of diaspora creating socially conscious narratives offering a peephole into these communities. Louisa is also the co-founder and communications coordinator for #500words.

-

1.

Rebecca Lewis, “Calling all Models: Size 12 and over need not apply”, NZ Herald, January 18, 2009, accessed August 30, 2015, http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10552389/.

-

2.

First wave feminism started during the nineteenth century with a focus on suffrage, specifically the promotion of equal contract, marriage, parenting, and property rights for women. Following from that second-wave feminists saw women’s cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked, encouraging women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicised and that reflected dominant sexist power structures. Third-wave feminism emerging approximately in the 1990’s distinguished itself from the second wave basing itself if the fact that women are of all nationalities, religions and cultural backgrounds and challenging female hetero-sexuality and celebrating sexuality as a means of female empowerment. Continuing on from that, post-feminists believe that women have achieved second wave goals while being critical of third wave feminist goals.

-

3.

“21st Sentry Cyber Sister by Pacific Sisters,” Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, accessed August 30, 2015, http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Topic/1547.

-

4.

Real_Talk101, forum post on Topix, “Why are Maori/Polynesian women so disgusting and annoying.”, accessed October 7, 2015, http://www.topix.com/forum/world/new-zealand/TK9BAF2MBJFJFR1OV.