The Occasional Journal

Love Feminisms

November 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton -

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt -

Considering Merata Mita’s Legacy

Chloe Cull -

Armour. Armor. Amor. More.

Zoe Crook -

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo -

This mud body

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa -

CONVERSATION

Creek Waddington, Sian Torrington -

Bloody Women Artists

Ruth Green-Cole -

the blue between me and you

Jo Bragg -

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans -

A guide

Rachel O’Neill -

Gender and the ANZAC Biscuit

Lindsay Neill -

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans

According to Sherilyn MacGregor, the built environment is a force which shapes our lives in profound ways.1 The physical forms of our public spaces, along with our social codes, dictate our actions within them. You wouldn’t lay down a picnic blanket and read a book on a busy footpath, but at a park you may do so without feeling conspicuous. Our urban environment enables or discourages us from enacting, or even conceiving of desired activities, and this makes architecture and urban design a topic of concern to everyone.2

Despite its significant implications for all members of the population, the practice of architecture and urban design in Aotearoa New Zealand has been overwhelmingly dominated by men. The patriarchal lineage of New Zealand design professionals has produced variable results for the community; the spatial qualities of our buildings and public places range from fantastic to terrible, as do their environmental performances. Male-generated urban design has also been discriminatory toward many people, and especially women.3

This essay explores problematic design in Wellington, New Zealand through a gendered lens in keeping with Aaron Betsky’s definitions of masculine and feminine as they apply to architecture.4 The writings of feminist designers and design collectives provide both critique and solutions from this binary perspective. Throughout the discourse, flaws in the binary narrative emerge, and ultimately I argue that the solution is not a simple one, but rather a nuanced integration of design philosophies which reflects the complex composition of our society. Te ao Māori does not see tane and wahine as a dualism,and, as Leonie Pihama describes, “there is a multiplicity of relationships within those terms.”5 I believe we need to embrace and explore such multiplicities, working towards a “non-sexist, sustainable city.”6

CRITICAL GROUNDWORK

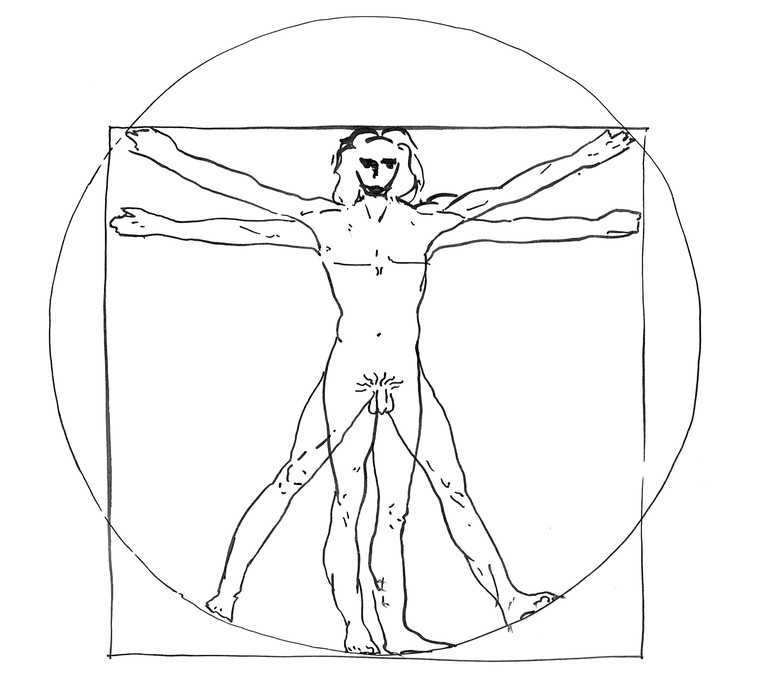

Even though the words masculine and feminine are loaded with connotations, I’m going to use them to describe design processes and their attributes. While masculinity and femininity in our culture are associated with the sexes,7 the terms as I am going to use them are not intended to imply biological traits, but to take advantage of the ubiquitous western understanding of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ in order to illustrate an argument. The idea of masculine is distinct from men, and feminine distinct from women. Aaron Betsky illustrates western conceptions of masculinity and femininity as a binary8 through the renaissance conception of the Vitruvian Man.

Rosie Evans, A Vitruvian Man, ink on paper, 297 × 210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

Man or the masculine is depicted as the dominating angular geometry; the man and the square which dominate over, but are also enclosed within the woman, or the feminine, as represented by the circle.9 Henceforth, when using the terms masculine and feminine I mean them to conjure the following associations:

Rosie Evans, m, ink on paper, 297 × 210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

Masculine: Seen as the harder side of human nature; powerful, pragmatic, visionary, imposing, with dominion over land and people, vision-focused and empowered. Carves his environment.

Rosie Evans, 7, ink on paper, 297 × 210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

Feminine: Seen as the softer side of human nature; caring, empathetic, nurturing, compromising, serving, with understanding of land and people, compassionate. Sculpts her environment or self.

OVERSIGHT AND EDUCATION

Societal notions of gender shape the activities commonly performed by men and women—in Women and the Urban Environment, Sue Cavanagh offers the example that women are more likely to be found in caring roles.10 The differing activities typically performed by men and women result in broadly gender-specific spatial requirements and perceptions.11 has been claimed that because urban design has long been mostly performed by men, the spatial requirements of activities commonly performed by women are often overlooked.12 Describing the reason for poor provision for women’s activities in parks, Clara Greed states “the majority of providers and policy makers are male, and it simply doesn’t occur to them, it’s not important to them, they don’t find it a problem.”13 I find this a problem.

The inference of Greed’s statements is that simply changing the gender ratio of designers will result in more representative design, as men only understand the needs of their gender. There are two problems with this. Firstly, it assumes that men cannot understand the spatial needs of women, and that not considering them is somehow an in-built flaw of the gender, like the potential for colour-blindness, rather than professional negligence and a culture of not looking. It is the job of a designer to understand the needs of the user. Secondly, it assumes that women inherently can and always understand and design for the needs of women.

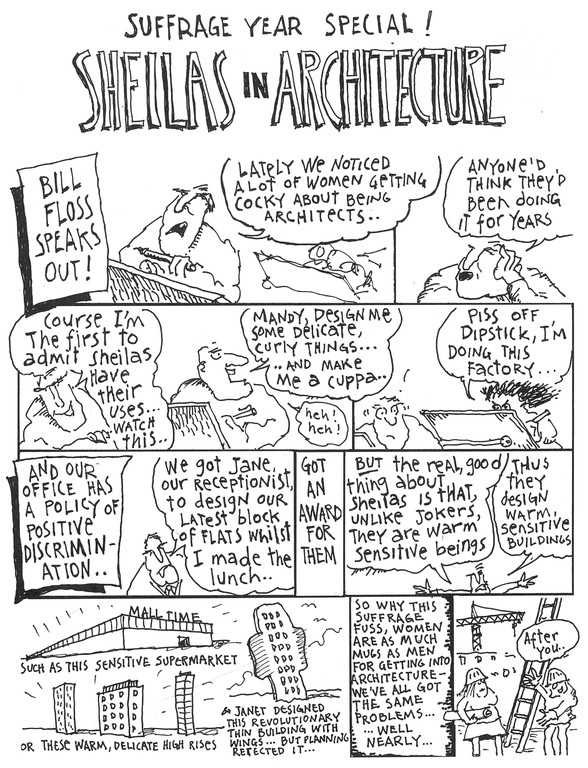

However, the realities of working in the architectural profession mean that a gender balance in architectural output requires a more than just a gender-balanced input, as Malcolm Walker’s cartoon about women architects in New Zealand illustrates:

Malcolm Walker, Sheilas in Architecture, ink on paper, 1993. © Malcolm Walker

Women can produce designs just as terribly as men. Jane Dark, a British feminist, architect and writer, blames architectural education, decrying it as a ceremonial passage into middle-classed-manhood for all who enter.14 Darke names the acclimatisation to a male modus operandi which occurs through a woman’s architectural education as part of a process which removes her from the women and communities she will design for. As a woman architecture student, this is an uncomfortable thought, but not an unfamiliar one.

If an architectural education is an equaliser, the gender of the designer may be irrelevant.

WHANGANUI-A-TARA, AOTEAROA

Aotearoa New Zealand was the world’s last British colony. Originally settled by Māori in the thirteenth century, European occupation of our Pacific isles began in the eighteen-hundreds, leading to a treaty which formalized the relationship between the crown of Queen Victoria, and many (but not all) of the Māori tribes. Britons sought to profit upon this new colony, and the New Zealand Company, a commercial operation based in England, became instrumental in the growth and formation of our present towns.15

The New Zealand Company, under the governance of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, purchased land for nominal sums from local iwi, and advertised a “Britain of the South” to British investors — many of whom held no intentions of living in New Zealand.16

In 1839 the New Zealand Company acquired Whanganui-a-Tara, the great harbor of Tara, which came to be known as Wellington, from the chiefs Te Puni and Te Wharepōuri.17 Today it is our capital city. Wakefield drew many of the original plans for Wellington and is often credited with being its founder; Wakefield Street, a major road by the waterfront, is named after him.

Rosie Evans, Ed Wakefield, ink on paper, 100 × 150mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

BIRDSHIT

Wellington was drawn up in England, and designed in plan, or from a bird’s-eye view. The method of designing from above is one dimensional, and assumes an omniscient, imposing stance that often disregards the landscape.18 Wakefield designed utilizing a gridded city format, which was motivated by an economic model for land division. This mode had little respect for the landscape it was applied to.19 Dubbed by Jan Gehl as “birdshit architecture” (i.e. plopped in from above),20 it has resulted in illogical building placement and poor sun exposure for many houses. In Newtown and Island Bay, the placement of the house on a section has been pre-determined by the gridded plan. Present city planning rules around setbacks and side-yard requirements perpetuate these historic and inefficient practices, resulting in situations like this (see figure below) on Coromandel St, where the topography offers an opportunity for passive design which is thoroughly disregarded.

Rosie Evans, Under-utilised North faces of houses on Coromandel Street, Newtown, ink on paper, 297 × 210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

These houses are on a North-facing gentle incline. They each have large faces which receive all day sun, and yet their windows have been laid out so as to standardise each house’s relationship to the street, rather than to provide optimum light and warmth to their inhabitants. This design fails to consider the physiological needs of the inhabitants over the cost efficiency of standard house and road design.

Jane Jacobs espoused that “there is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”21 This ethos has not been a strong feature of our city’s formation, the above being a common example of people having to fit to a super-imposed plan logic. Wellington requires a design approach which acknowledges the uniqueness of each site, and with empathy for building inhabitants.

CLAIMING

One of the most literal urban translations of Betsky’s reading of the masculine as man over nature22 manifests in the form of land reclamations. Creating land where there was once water or marsh produces environmental and inhabitation problems, where biodiversity is lessened through loss of habitat, and land is prone to flooding during fluctuations in the water table, and will be placed under increasing pressure as the sea level rises.23

Because solid land is foreign to the place of reclamation, it will always be under water stress, and often comprises of a softer soil type than the surrounding area, which is more susceptible to earthquake damage, placing inhabitants at risk. Since the 1840s land reclamations in Wellington over sea and swamp areas have been extensive. The resultant land is almost entirely shake-prone and constitutes some of the city’s most densely populated areas.

Rosie Evans, Wellington’s Shakey Reclamations, mixed media, 297 × 210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

Left panel: Yellow = reclaimed, Centre panel: Yellow = hazard area, Right panel: Yellow = hazardous reclamation

Map 1 shows land which is forward of the 1840 Wellington Shoreline; this land has been built up in a series of reclamations since 1840. Map 2 shows land which the Wellington City Council deems as an ‘earth-shaking hazard zone’; note the elongated passages to the left indicate drainage areas from the surrounding hills. Map 3 indicates the extent to which the land shaking hazard zone overlaps with reclaimed land, a large proportion of the hazardous land in Wellington is reclaimed. (Maps adapted from 2015 Wellington District Plan of Central Wellington and Pipitea area).24

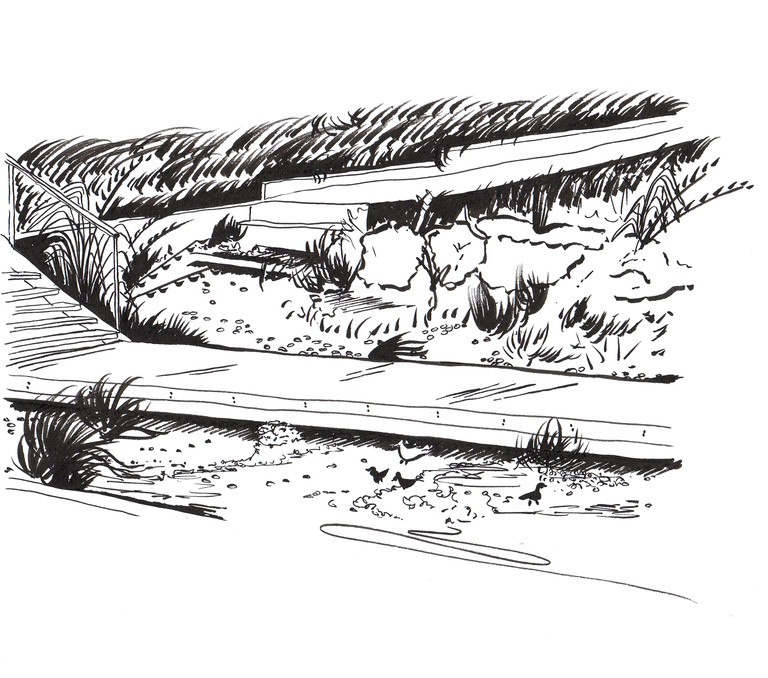

In sites where reclamations have already taken place, a sensitive approach to continuing development is welcome. The design of Waitangi Park on Wellington’s waterfront seeks to return the natural function to the land. Because reclaimed land is entirely constructed and therefore has no original function, one must be constructed. To do this, Megan Wraight and Associates have shepherded under-ground streams and storm-water drains, and allowed them to flow above ground into the seaside park. The park operates as an urban wetland, the water drains through channels of gravel, native moss, grass and flax, and water-borne toxins from road run-off are filtered by the plants and captured, rather than drained into the sea.25 The water leaves the park cleaner than it arrived.26

Rosie Evans, Waitangi Park, ink on paper, 297x210mm, 2015. © Rosie Evans

NATURAL / WOMAN: THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS OF GENDER EQUITY

Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant has drawn connections between man’s attitudes towards nature and women, stating that their association with nature gives licence for male domination of women, in equivalence with the domination of nature as man’s domain.27 If we accept this connection, which also falls within Betsky’s characterisations of male and female drawn from the Vitruvian man, then it stands to reason that addressing destructive masculine design practices28 will have both gender and environmental benefits.

While addressing past design practices may serve the environment, I wonder who it is serving to characterise historic design practices as masculine. If contemporary female designers are just as capable of executing environmentally damaging projects, surely the fault, and therefore also the grammatical inference, must lie with all of us. A more constructive way forward is from a point without guilt or grievance imbedded in the language.

There is a significant overlap between the design outcomes advocated by both feminist writers and environmentalists.29 If we re-organise Merchant’s sentiment, loaded as it is, we can hypothesise that addressing destructive environmental practices will create positive outcomes for gender-equality. Sociologist Margrit Eichler in her book Change of Plans: Toward a non-sexist, sustainable city, highlights design principles common to both proponents of the Feminist City,30 and environmental advocates.31 These principles include:

- friendly neighbourhoods through mixed use of space and lively streets orientated towards pedestrians rather than cars;

- providing a network of social services;

- a first-class public transportation system that is safe, cheap and efficient;

- reducing car dependency;

- an active social housing policy which includes co-operative housing, housing for women leaving transitional homes, and special housing for women with disabilities;

- access to healthy food, with urban agriculture and transitional cropping;

- active encouragement of community-based, economic development, with meaningful jobs for women, co-ordinated with day-care;

- encouraging social equity;

- a close physical relationship between services, residences and work-places, encouraged by mixed land use.

- facilitating multiple uses of built forms;

- compact design.

Thanks largely to Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl, since the 1960s urban design theory has been feminised. The placeless plan a la Edward Gibbon Wakefield is no longer in fashion, and people-centric practice is key. Men and women have been schooled in, and are teaching, a compassionate approach which is both socially and environmentally responsive… And yet, there is still a way to go.

By naming her ideal city in a non-gendered way, a non-sexist, sustainable city, Eichler invokes a gender-inclusiveness which may appeal to today’s (still mostly male) designers. While the term is mellower than the battle-cry associated with feminism and the feminist city, and may ultimately catch more bees with honey, the trade-off is that it is no longer imbued with the strength and rigour of generations of feminist activists and urbanists. Shying away from the term feminist, while strongly espousing feminist beliefs places Eichler’s terminology on interesting ground; does it signal watered-down and appeasing feminism, or is it the new iteration of inclusive feminist terminology? In my own practice I often worry whether the tempering of language is motivated by compassion or cowardice.

SEPARATION. CITY / SUBURB / WORK / HOME

Feminist writers such as Dolores Hayden advocate for mixed-use of land and buildings to addresses the social injustice arising from the dispersion of home and work.32 According to Professor of Inclusive Urban Planning Clara Greed, “the dominant twentieth century metropolitan spatial form is that of a city of separate spheres; the masculine city and the feminine suburb.”33

Problems arise from binary division of city and suburb like this; when one place (the city) is percieved as a place of ‘work’, the other can be construed by default as a place of ‘non-work’.34 When places are characterised by gender, as Greed suggests, the work undertaken by women in the suburbs in devalued.35 The associations flow; city–men–work, vs. suburb–women–don’t–work. Activist Marilyn Waring quotes U.S Senator Daniel Moynihan on the fact that ‘women’s work’ is undervalued, leading to social disrespect and inequality:

If American society recognised home-making and child-rearing as productive work to be included in national economic accounts the receipt of welfare might not imply dependency. But we don’t.36

Commentary following the 2015 New Zealand budget made it very clear those biases are still strong here too; although benefits rose by $25 a week,37 in return for this payment solo parents, primarily mothers, will be “sent back to work”38 (paid employment) two years earlier, pay for children to be in childcare, and work for 33% longer than previously stipulated.39 The values producing these discriminatory policies can be seen within the urban form of our cities. Waring identifies that in the current economic framework, the value of women’s domestic labour, and the value of our environment all count for nothing economically, and yet these accounting systems (which exclude women and their ecomomic and other contributions) are used to determine all public policy.

TRUE FEMINIST DESIGN

Contrary to the tenor of some literature I don’t think women hold all the answers, nor should we. The binary of man as insensitive and woman as the saviour of the planet belittles fantastic men, and places an outrageous expectation upon the shoulders of the very few women in design. Besides which, it’s bogus! Why should men be less compassionate or inherently connected to nature than women? As illustrated in Malcolm Walker’s Sheilas cartoon, and outlined by Joni Seager, “not all women are naturally equity seeking and life enhancing, nor can it be assumed that they would be so if removed from the constraints of patriarchy. Men may treat nature as a woman and women as nature, but this does not mean all women actually experience a closeness to nature.”40 Women do not inherently design warm, environmentally aware, sensitive buildings.41 It is argued that an architectural education strips women of these impulses; but if an architectural education is some sort of passage into manhood for female students,42 then any mental gender-gymnastics is possible, proving that a designer’s sex is largely irrelevant. What we need is not more female designers, it’s more feminist ones.

I am not saying we don’t need more women designers. It is still true that growing up either male, or female in this society creates cultural blind spots, which can be illuminated by the opposite sex. What I am saying is that we can all learn to ask, and to listen. Resorting to a gender binary to describe the complexities that exist in our built environment is an overly-simplistic, futile and destructive exercise, which perpetuates opposition, and devalues the wholeness of members of any sex.

Male generated urban design has caused many issues; it has been discriminatory toward many/women, individualistic and damaging to the environment. Feminist urbanist writers and academic queer advocates have termed this a ‘masculine’ problem,43 and tabled ‘feminine’, or ‘feminist’ design solutions, but to name the solution to negative historic design practices as feminine over-simplifies the problem.

Associating bad design and good design with male and female design philosophies invokes a binary which ostracizes and under-estimates the potential of many good men and women. An empathic and environmentally responsible urban design future needs us all.

About the author

Rosie has studied Fine Arts and is about to complete a Bachelor of Architectural Studies at Victoria University of Wellington.

-

1.

Sherilyn MacGregor, “Deconstructing the Man Made City: Feminist Critiques of Planning Thought and Action,” in Change of Plans - Towards a Non-Sexist, Sustainable City, ed. Margrit Eichler (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1994), 26.

-

2.

Ibid.

-

3.

Clara Greed, A Place for Everyone? Gender Equality in Urban Planning A ReGender Briefing Paper (London: Oxfam, 2007), accessed September 3, 2015 www.apho.org.uk/resource/view.aspx?RID=93623.

-

4.

Aaron Betsky, “Queer Space” (Lecture delivered at Southern California Institute of Architecture, Los Angeles: 22 March, 1995), minutes 14-16, accessed June 10, 2015, http://sma.sciarc.edu/video/aaron-betsky-queerspace/.

-

5.

Leonie Pihama, quoted in J. Hutchings, “Te whakaruruhau, te ukaipo: Mana wahine and genetic modification.” (PhD diss., Victoria University of Wellington, 2002), 37, accessed June 4, 2015, http://www.kaupapamaori.com/assets//HutchingsJ/te_whakaruruhau_chpt2.pdf

-

6.

Margrit Eichler, Towards a Non-Sexist, Sustainable City, ed. Margrit Eichler (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1994).

-

7.

Matrix, Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment (Bristol: Photobooks Limited, 1984), 7.

-

8.

Aaron Betsky, “Queer Space”, minutes 14-16.

-

9.

Ibid.

-

10.

Sue Cavanagh “Women and the Urban Environment”, in Introducing Urban Design: Interventions and Responses, ed. Clara Greed and Marion Roberts (Harlow: Longman, 1998), 167-168.

-

11.

Matthew Carmona et al., Public Places, Urban Spaces, Second Edition (Oxon: Routledge, 2010), 164.

-

12.

Jos Boys et al., Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment (Bristol: Photobooks Limited, 1984), 7.

-

13.

Clara Greed, Inclusive Urban Design: Public Toilets (Oxford: Architectural Press, 2003) 6.

-

14.

Jane Darke, “Women, architects and feminism”, in Making Space: Women and the man-made environment, ed. Jos Boys et al. (Bristol: Pluto Press, 1984), 12-13.

-

15.

Jock Phillips, “History of Immigration - British Immigration and the New Zealand Company,” Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed August 21, 2015, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/history-of-immigration/page-3.

-

16.

Ibid.

-

17.

Ibid.

-

18.

Jan Gehl, “Bird Shit Architecture in Brasilia and Beyond” (Lecture delivered at Melbourne Town Hall: 2 May, 2011), minutes 14-16.30, accessed August 10, 2015, http://library.fora.tv/2011/05/02/Jan_Gehl_Cities_for_People.

-

19.

Jock Phillips, “History of Immigration - British Immigration and the New Zealand Company,” Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

-

20.

Jan Gehl, “Bird Shit Architecture in Brasilia and Beyond”, minutes 14 – 16:30

-

21.

Jane Jacobs, “Downtown is for People,” Fortune Magazine, accessed June 20, 2015

http://fortune.com/2011/09/18/downtown-is-for-people-fortune-classic-1958/ -

22.

Aaron Betsky, “Queer Space”, minutes 14-16.

-

23.

Jens Rekker, Sea Level Effects Modelling for South Dunedin Aquifer (Dunedin: Otago regional Council, 2012), i-1.

-

24.

“District Plan, March 2015 edition” Wellington City Council, accessed May 22, 2015, http://wellington.govt.nz/your-council/plans-policies-and-bylaws/district-plan/volume-3_-maps.

-

25.

“Waitangi Park,” Wraight and Associates Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, accessed May 22, 2015, http://www.waal.co.nz/our-projects/urban/waitangi-park/ (accessed May 22, 2015).

-

26.

“City Underground Streams, March 2013” Wellington City Council, accessed May 22, 2015, http://wellington.govt.nz/your-council/news/2013/03/city-underground-streams.

-

27.

Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1990), pp.290-94.

-

28.

Aaron Betsky, “Queer Space”, minutes 14-16.

-

29.

Margrit Eichler, “Designing Eco-City in North America”, in Towards a Non-Sexist, Sustainable City, ed. Margrit Eichler (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1994), 17.

-

30.

Based on Andrew, 1992 summary of the main principles of the available feminist urban design literature.

-

31.

Based on Klaus Dunker’s principles for a sustainable city.

-

32.

Dolores Hayden, “What Would a Nonsexist City Be Like?: Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work,” in Gender and Planning: A Reader, ed. Susan S Fainstein and Lisa J Servon (New Jersey: Rutgers, The State University, 2005), 60.

-

33.

Clara Greed, A Place for Everyone? Gender Equality in Urban Planning A ReGender Briefing Paper.

-

34.

Marilyn Waring, Counting for Nothing (Wellington: Allen & Unwin/Port Nicholson Press), 5.

-

35.

Dolores Hayden, “What Would a Nonsexist City Be Like?: Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work,” 60.

-

36.

Daniel Moynihan, quoted by Marilyn Waring, Counting for Nothing, 6.

-

37.

“Solo mums will be pocketing a little extra cash thanks to today’s Budget, but the heavier wallet comes with some strings attached. Thu, May 21,” One News, accessed june 5, 2015, https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/budget-2015-beneficiaries-will-be-sent-back-to-work-sooner-6317604.

-

38.

Ibid.

-

39.

Ibid.

-

40.

Jeanne Jabanoski, “At Risk:The Person Behind the Assumptions”, Change of Plans - Towards a Non-Sexist, Sustainable City, ed. Margrit Eichler (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1994), 73.

-

41.

See Malcolm Walker, Sheilas in Architecture, ink on paper, 1993.

-

42.

Jos Boys et al. Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment, 7.

-

43.

Aaron Betsky, “Queer Space”, minutes 14-16 .