The Occasional Journal

Love Feminisms

November 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton -

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt -

Considering Merata Mita’s Legacy

Chloe Cull -

Armour. Armor. Amor. More.

Zoe Crook -

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo -

This mud body

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa -

CONVERSATION

Creek Waddington, Sian Torrington -

Bloody Women Artists

Ruth Green-Cole -

the blue between me and you

Jo Bragg -

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans -

A guide

Rachel O’Neill -

Gender and the ANZAC Biscuit

Lindsay Neill -

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Figure 1: George Crombie, Snapped, 1912, gelatin silver glass plate negative, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: B.047398. Purchased 1999 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds.

What do you write about a photographic history that includes the unconventional (and at times unremarkable yet essential) involvement of women as makers and consumers of photography? A record that acknowledges the value of the photographic work of women and addresses the problem of defining that work on its own terms? I am interested in the material legacy of photographs by early woman photographers in New Zealand museums and archives (or the lack thereof), and the question of how to rethink curatorial concerns that have been formed by histories that have excluded, not only work relating to New Zealand, but the work of women.

Traditional historical methods that could be applied to a history of women and photography related to New Zealand are unsuitable and unrealistic tools to analyse types of photographs women tended to make and the circumstances of their production. An art historical approach is too concerned with artistic genius, oeuvres, innovation and technical excellence. Technological and social history approaches focus on the photographic apparatus, its operation, and its role in recording historic events, themes and personalities. There is no photographic equivalent to Anne Kirker’s New Zealand Women Artists.1 The kind of photography early woman photographers were involved in making — namely commercial portraiture — doesn’t rate highly in retrospective historical accounts where the focus is on work that can be argued to have stood out in some way from the mass of photographs made in the nineteenth century.

The key major publications on photography and New Zealand are: Hardwicke Knight’s Photography in New Zealand – A Social and Technical History,2 where the only woman discussed amongst the small number of notable photographers is Thelma Kent; John Turner and William Main’s New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the present,3 which lists seven early woman photographers; David Eggleton’s Into the Light – a history of New Zealand photography,4 which draws on previously published articles (see later this paragraph) to profile several early woman photographers; and the latest publication, Athol McCredie’s New Zealand Photography Collected,5 which features a strong number of women photographers from the mid twentieth century onwards but very little by woman photographers working prior to 1940. There are also a few substantial essays focused on single early woman photographers; such as Tim Walker’s work on Margaret Matilda White,6 Vicki Hearnshaw on Harriet and Rosa Acland,7 Gerard Hindmarsh on Rosaline Frank and her involvement in the Tyree Studio,8 and the indispensable website Early New Zealand Photographers, compiled by Tony Rackstraw from Christchurch,9 which pulls together the most comprehensive primary sources on early photographers in relation to New Zealand.

Despite the ambitious scope of the aforementioned books, the role of woman photographers working prior to 1940 is largely overlooked. I want to determine the involvement of women and assess their output as photographers but there is so little on the public record — whether through neglect or because of the sheer mass and formulaic nature of early photography — which was Empire wide and thereby obliterated the individual output of those who made it. Social conditions led women to work mainly in the studio context, with a focus on collective and factory style practices, while history has taken more of an interest in the expeditions of individual photographers, such as Alfred Burton in the 1880s and Daniel Mundy in the late 1860s. It seems that to have been a woman photographer in New Zealand during the nineteenth century was to be among the overlooked mass of commercial portrait photographers working within the interior confines of studios. As yet little has been written about this economy of portrait making, its makers, and clients.

It is easy to assume museums and archives will hold an accurate record of all historical material culture; one that is inclusive and covers all forms, aspects and manifestations of photographic practise. However, this is not the case: collecting policies for institutions specifically focus on the assessment of art and artefacts in terms of their relationship to the historical canons of art and history and the national and/or regional significance of objects and resources. Individuals may not recognise the value of unwanted heirlooms, and institutions cannot take everything that is offered to them. Despite the fact that there were many women running very successful studios, especially from 1890 onwards, very little of their work has been collected (or if it has, may not be attributed to them). As for what has not been collected, simply too much time has passed and this material has often been cleared away and disposed of as people moved on and times changed.

So, how to write a history of early (in this case, up to 1940 but primarily focusing on the nineteenth century) women photographers working in New Zealand when so few of their photographs are recorded and held in institutional collections? There are two main factors that have lead to the role of early woman photographers being largely written out of history. Firstly, women tended to work in the area of commercial portrait photography — an area that has been mostly sidelined in histories of the medium. Secondly, in terms of women with artistic aspirations working in photography, their involvement tended to be as amateurs and within the camera club movement, which at the time largely focused on recording the efforts and achievements of clubs’ male members. Until recently the genre favoured by the Camera Club movement — Pictorialism — was ridiculed as ‘fuzzy pictures’ and marginalised in histories of art and photography in this country and elsewhere.

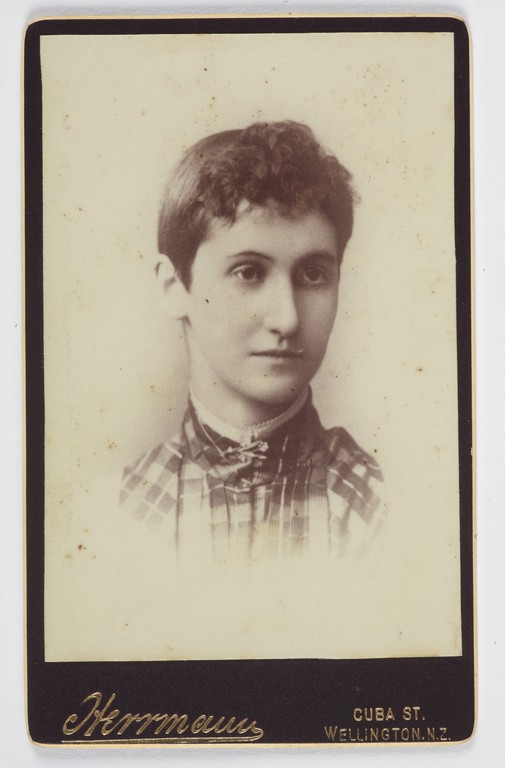

Figure 2: Louisa Herrmann, Woman, 1890s, albumen silver carte-de-visite print, 101x62mm , Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: O.005347. Gift of an anonymous donor, 1972.

Sadly much of the work by early woman photographers that is in institutional collections is poorly documented, especially in terms of attribution. Many women, such as Louisa Herrmann of Wellington, used only their surname on their work and this has often been assumed to be a man’s name. Herrmann initially set up a studio with her husband and, after his death two years later, continued to operate the studio alone through the 1890s using just her surname printed on the mounts of her studio portraits (figure 2). This was a common scenario for many women whose husbands passed away, such as Elizabeth Pulman of Auckland and Agnes Robottom of Ashburton.

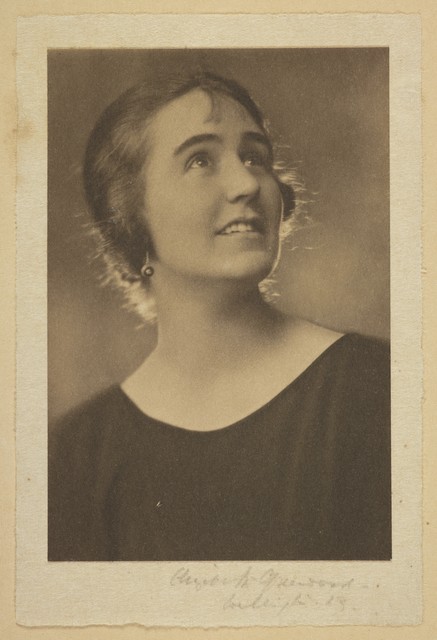

Figure 3: Elizabeth Greenwood, Portrait of a young woman, 1923, gelatin silver print, 183x126mm, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: O.021007. Purchased 1999 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds.

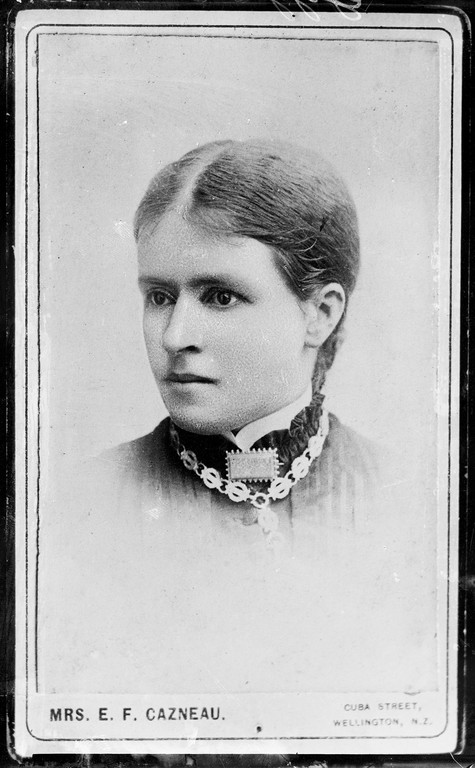

In the case of another Wellington photographer, Elizabeth Greenwood, there are instances where her signature on the print has been treated as not the signature of the photographer, but the name of the woman in the photograph (figure 3). On the other hand, Emily Cazneau released photographs made in her Wellington studio with her name printed on the mount as “Mrs E. F. Cazneau” (figure 4). This studio was a partnership with her husband, Pierce Mott. Cazneau initially trained and worked as a colourist and miniature painter in the Freeman Brothers’ photographic studio in Sydney during the 1860s before coming to New Zealand. The Cazneaus operated studios in Wellington from the early 1870s until 1890 when they moved to Adelaide. Their son, Harold Cazneaux (born in Wellington in 1878, later adding an ‘x’ to his surname) became one of Australia’s most iconic and revered twentieth-century photographers.

Figure 4: Emily Florence Cazneau, Geggel, circa 1920, glass copy negative of a carte-de-visite photograph made by Berry & Co, circa 1885, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: B.046379. Purchased 1998 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds.

In her 1980 article, “Early women photographers of NZ”, Rosemary Bevan regarded the hard physical work involved with creating outdoor wet-plate photography as the main impediment for early woman photographers. She also noted that women may have been reluctant to get their hands stained by photographic chemicals, which would have been socially unacceptable at the time.10 While these may have been factors preventing women from making photographs, they were not the end of the story and they did not stop some women taking on the medium. Bevan was also concerned that New Zealand had not produced an equivalent early women photographer to Britain’s Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) and ends her article by expressing the hope that one might yet be discovered as future research develops in this area. But this is beside the point; we cannot judge and value the history of photography related to this country simply within the terms of how it measures up to exceptional aspects of the history of British photography. We will not find another Cameron here and we should not expect to, but we will find other things — learning to value them is what matters.

Figure 5: Marie Dean, Child with a seashell, 1920s-1930s, gelatin silver print, 148x98mm, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: O.021014. Purchased 1999 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds.

By the early twentieth century, portrait photography was acknowledged as a suitable profession for women because it was light physical work and the styling of portraits was seen to benefit from the input of female taste. As a large proportion of the clients of portrait studios were women and children, woman photographers had an advantage because it was more socially acceptable for a woman to suggest alterations to customers’ clothing and physical appearance than for a man.11 Marie Dean, who operated a studio in Cuba Street, Wellington during the 1920s and 1930s, is an example of a successful woman photographer whose studio specialised in taking portraits of children. Many of Dean’s portraits are of women and infants and she had the ability to make beautiful and relaxed portraits that avoided some of the well established cliques of the studio format at the time. For example, posing a child listening to a sea shell (figure 5), and looking off camera as if contemplating the sound of the sea far away, moves away from the established format of children in studio portraits absently holding a ball or posy of flowers.

In their 1986 article, “Women Photographers in the Turnbull Library”, curators Joan McCracken and John Sullivan give a more detailed, though brief, overview of early woman photographers including a Mrs Hamilton (an early Wellington photographer about whom little is known) and Louisa Herrmann, before turning their attention to more recent work.12 These two articles are the only attempts at any sort of survey or short history of early woman photographers working in New Zealand thus far.

Any account of women, photography, and New Zealand needs to be supported by material evidence: photographs made by women. These histories need to review archives and their makers in a manner that attempts to understand the original context of production, including the social and economic factors that enabled and inhibited women in making photographs and the communities that their work was produced and circulated within. In the colonial period, the key areas of focus would be the main areas woman photographers (or women making photographs) worked — commercial portrait studios and the Camera Club movement.

One of the early proponents of the autochrome process in New Zealand was Elizabeth Greenwood. Greenwood operated a commercial portrait studio in Woodward Street and was an active and successful member of the Wellington Camera Club, where her involvement extended to giving lectures on photography and judging competitions. But for a few commercial portraits, Greenwood’s work is virtually absent from archive and museum collections. Most of Greenwood’s photographic material on the public record is visible only as reproductions in the New Zealand Graphic newspaper (figure 6). A few of her vintage prints are held in public collections, but the fate of her negatives and autochrome plates is unknown. The National Library of New Zealand has a small holding of her work; mainly panorama prints of Chilton Saint James School showing the buildings and students.

Figure 6: Elizabeth Greenwood, Expectancy, circa 1907, published in New Zealand Graphic, 16 March 1907, p. 3, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries: NZG-19070316-3-1.

Going by the numerous portraits by Greenwood reproduced in the New Zealand Graphic, it is possible to see that many of her portraits were routine shots showing the subject in either a head and shoulders profile or full length poses, mainly of women, in ball attire. The portraits show and name members of Wellington society during the early years of the twentieth century. Some of her portraits of women appear to represent the subjects in reflective anticipation of something unknown. They depict women looking off camera and into the distance; either looking up (figure 3) or to the side as in Expectancy, (figure 6) where an elegantly dressed woman sits poised, waiting.

Figure 7: Marion Kirker, Street vendor, London, circa 1935-39, gelatin silver print, 242 x 301mm, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: O.039029. Gift of Anne Kirker, 1993.

One of the more successful early amateur woman photographers was Marion (Queenie) Kirker. Keen to study Pictorialist style photography in London, she left New Zealand in the mid-1920s and spent time learning the bromoil photographic process, which was a highly regarded medium of Pictorialism that enabled photographers to manipulate the look of the print for creative purposes. Kirker’s prints show her camera focused on scenes around the city including workers in the docklands, street vendors selling newspapers, fruit, or flowers, and pavement artists working along the Thames embankment. She particularly enjoyed the intricacy of working in the bromoil process and took to it as an art medium. In early 1937 Kirker became a member of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and was possibly the first New Zealand woman to do so. By mid-year she had been elected to the prestigious Associateship membership of the society.13 After returning to New Zealand and despite having a darkroom installed at home in Auckland, Kirker’s motivation to make photography waned in about 1945 without the stimulation and support of a serious creative camera community. However she returned to the medium in the early 1950s after purchasing a Paxette camera, and began working in snapshot mode in the new colour transparency format.14

With much of the material legacy of the work of early woman photographers largely missing from the public record, making their role invisible, perhaps some creative solutions are needed to help write women into the history of photography. As discussed with Elizabeth Greenwood, often the legacy of an early woman photographer is more contained within reproductive sources, such as historical newspapers, than in the form of vintage prints and negative collections. Contemporary photographers can play a role in making the histories of early woman photographers more visible through the creation of work that responds to and imagines the past. A good example, though it is not focused on woman photographers, is Lisa Reihana’s 1997 mixed media installation, Native Portraits n.19897. In this work Reihana reconstructed the working style of nineteenth century studio portrait photographers working with Māori subjects to contextualise new questions of indigenous identity and photographic representation.

As a curator I have been actively researching and attempting to seek out what remains of the work of early woman photographers for Te Papa’s collection. My focus is not on great moments in time, great people, or necessarily great art, but rather people and the communities they made, how they got by, what they valued, how they interacted with commerce and the general mobility and circulation of people and things. Photographs are primary sources that function as relics and repositories of visual information. It matters who took photographs during the nineteenth century and what they took photographs of. We need to find out as much as possible to broaden our perception of the different aspects of the photographic industry and the roles women had within it. The dominant story is too simple and does not account for the way women responded to the situations that enabled them to make photographs and be part of the photographic industry. By working in the portrait studio and the amateur realm, the work of women in early photography is by default concerned not only with economies but with people, places and questions of belonging.

—

The following is the start of a list of early women photographers whose work is held in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’s collection and includes a link to examples of their work on the museum’s Collections Online website.

Norah Carter (active 1911-1923)

Florence Eugenie Craig / Jubilee Studios (active about 1900-1905)

Marie Dean (active 1918-1950s)

Eileen Deste (active 1932-1943)

Rosaline Frank / Tyree studio (active about 1893-1947)

Marion (Queenie Kirker (1879-1971))

Louisa Herrmann (active 1890s)

Elizabeth Greenwood (1873-1961)

Mabel Tustin (active 1937-1952)

About the author

Lissa Mitchell is Curator Historical Photography at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

-

1.

Anne Kirker, New Zealand Women Artists (Auckland: Reed Methuen, 1986).

-

2.

Hardwicke Knight, Photography in New Zealand – A Social and Technical History (Dunedin: John McIndoe, 1971).

-

3.

John Turner and William Main, New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the present (Auckland: PhotoForum Inc,1993).

-

4.

David Eggleton, Into the Light – a history of New Zealand photography (Nelson: Craig Potton, 2006).

-

5.

Athol McCredie, New Zealand Photography Collected (Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2015).

-

6.

Tim Walker, “A Curious Dislocation: Margaret Matilda White’s Photographic Manner,” Art New Zealand 53 (Summer 1988-89): 96-99.

-

7.

Vicki Hearnshaw, “A New Zealand collection with English connections: the photographs of the Misses Acland,” New Zealand Journal of Photography (Autumn 2002): 4-6.

-

8.

Gerard Hindmarsh, “Images from the Frontier: The Tyrees’ Priceless Legacy,” New Zealand Geographic (April/June 1997): 54-70.

-

9.

“Early New Zealand Photographers”, accessed October 4, 2015, http://canterburyphotography.blogspot.co.nz/.

-

10.

Rosemary Bevan, “Early women photographers of NZ,” New Zealand Journal of Photography 5 (1980): 5.

-

11.

Arthur G. Willis, “The woman photographer,” in Photography as a Business (London: Henry Greenwood & Co. Ltd,1928), 3-4.

-

12.

Joan McCracken and John Sullivan, “Women Photographers in the Turnbull Library”, Turnbull Library Record, no. 19 (1), (May 1986): 52-60.

-

13.

“Admissions to the Associateship,” The Photographic Journal, Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain 77 (June 1937): 217.

-

14.

Author email correspondence with Kirker’s descendants Jim and Anne Kirker, May 2013.