All This Work Is Necessary

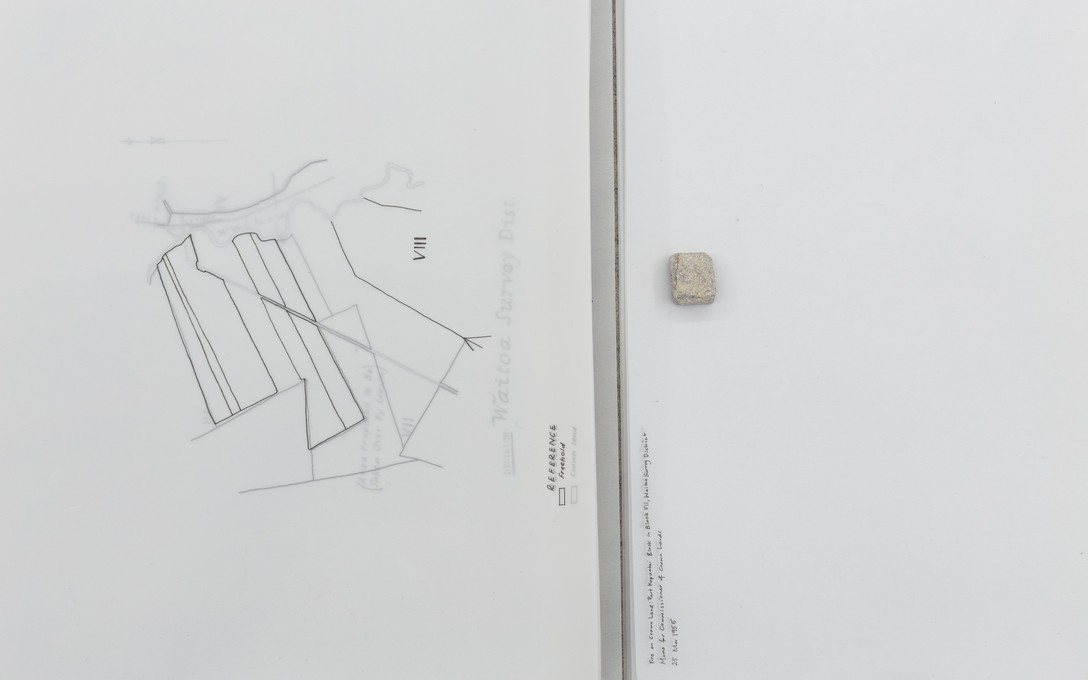

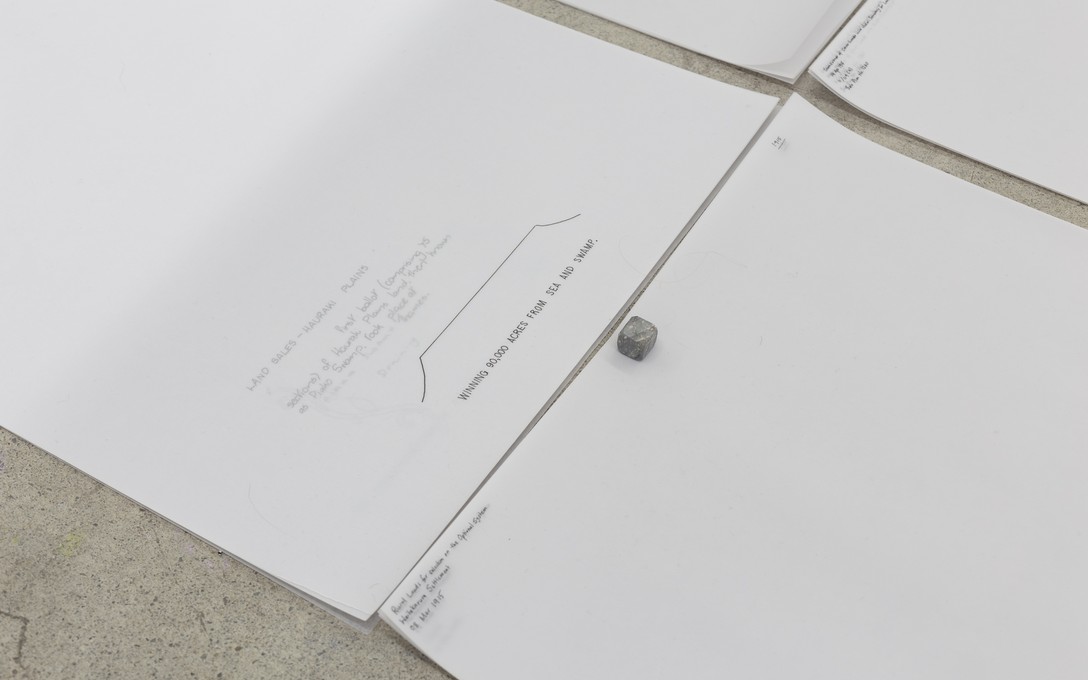

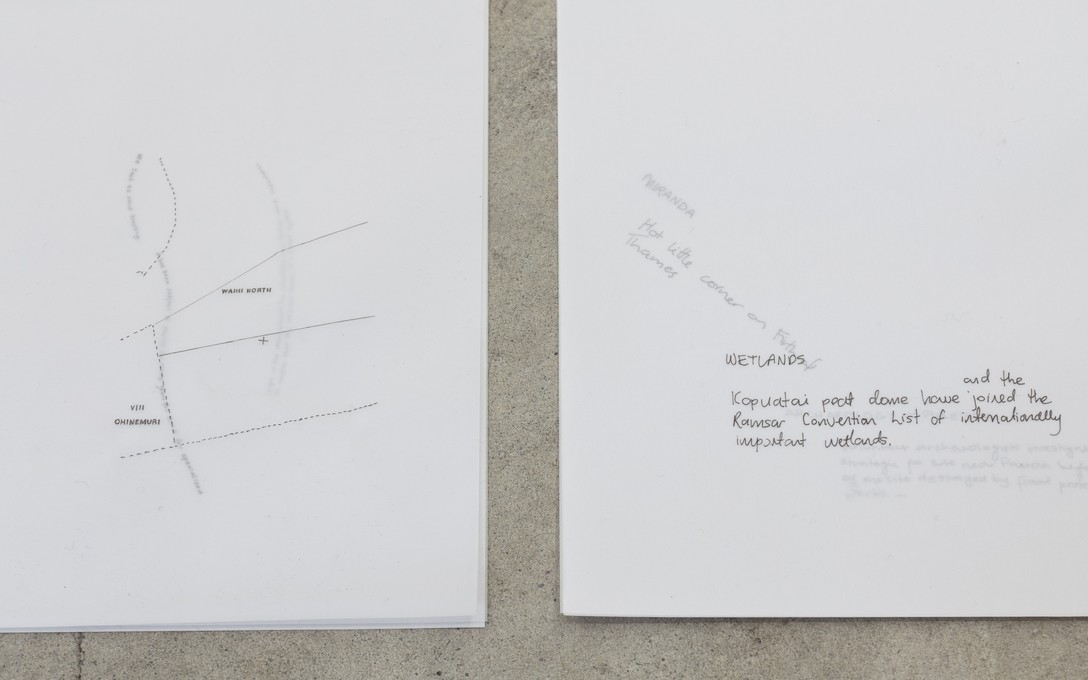

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

archived

24 Nov

2023

–

3 Feb

2024

Ashleigh Taupaki

Haere mai, nau mai

Haere mai, kuhu mai ki ngā hūhā o Ruawehea.

Welcome welcome

Welcome through the whakapapa of Ruawehea.

All This Work Is Necessary is an extension of Ashleigh Taupaki’s doctoral research investigating her Ngāti Hako connections to the Hauraki wetlands. The artist’s whakapapa is an essential part of her practice. Taupaki’s tūpuna are said to be the earliest settlers of Hauraki. Though Ngāti Hako records, such as pūrākau and waiata, have sadly been decimated over time due to inter-iwi wars and colonial settlement, she has spent years pouring over surviving records written by those who sought to oppress Māori through imperial power structures. The resulting artworks are a testament to Taupaki’s determination to convey the systemic decline of the Hauraki wetlands.

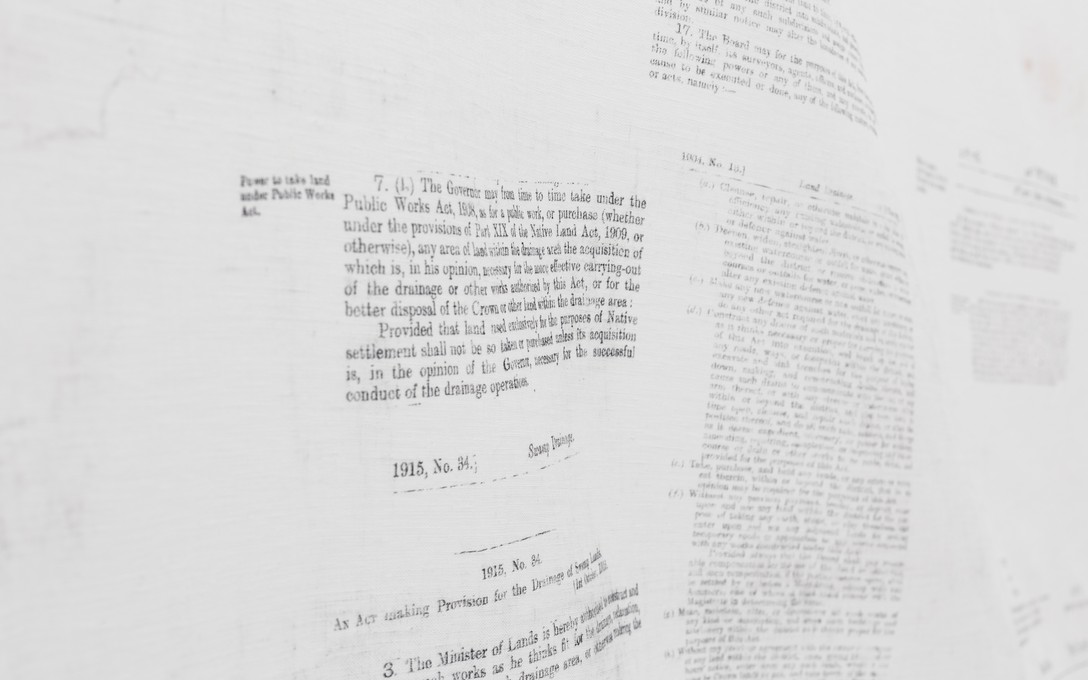

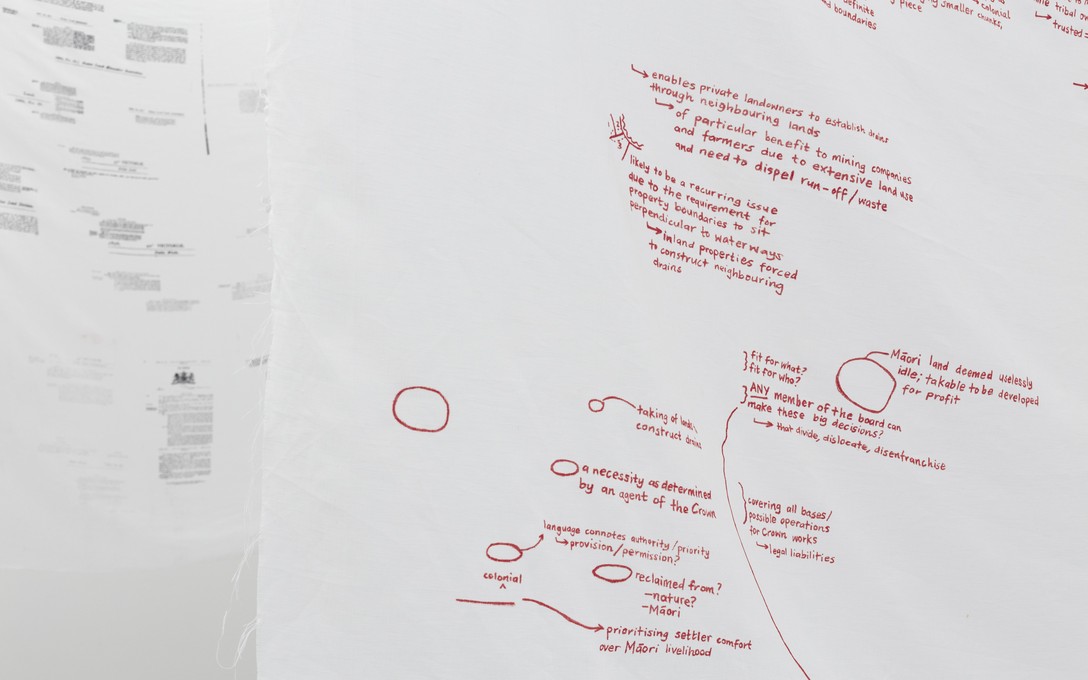

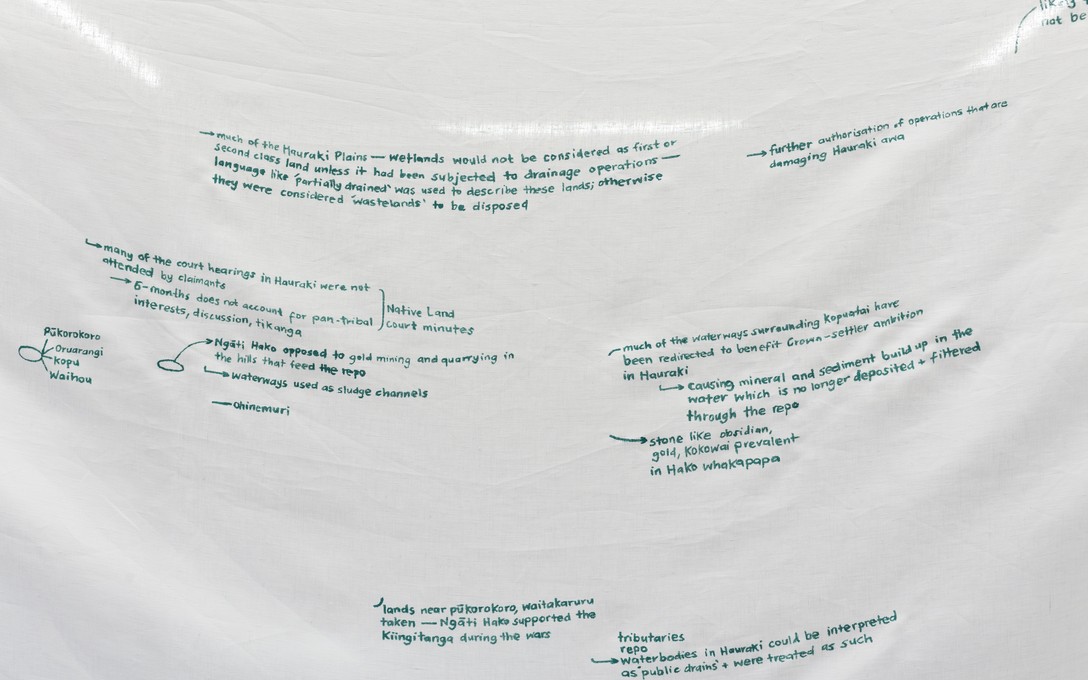

The wetlands in Hauraki have been irrevocably altered from their pre-colonial state. Once, the swamp land was rich with resources, including endemic species of plants, fish and birds. Māori cherished this taonga that provided mahinga kai, rongoā and materials for raranga and whakairo. Wetlands function as a boundary between land and water, filtering excess sediment and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. During European settlement, timber millers were attracted to the land due to kahikatea and soon felled the forest. Plans were then made to drain the swamp and convert the land into space for dairy farming. Throughout this process, carefully crafted legislation such as the Native Land Court was “designed for Pākehā purposes of freeing up Māori land from collective ownership and making it available to individual settlers.”

Mana whenua were alienated from their own rohe and thrust into survival mode. Taupaki acknowledges this and seeks to “restore the mana lost” from an Ngāti Hako perspective. She has previously stated that being in her tūrangawaewae begets a sense of wātea—wā meaning time and ātea referring to a communal space. With her own hand-written notes overlaid atop copies of archival material spanning a period of 200 years, Taupaki deconstructs the Western concept of time as linear. Other Māori artists and historians have described time in te ao Māori as “multidimensional” or as a “spiral”. Following their lead, Taupaki dismantles the colonial narratives that aided in Ngāti Hako land loss. In reaching back to the ‘time’ of her tūpuna and bringing it forth, Taupaki collapses the centuries between generations.

Renown scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith asserts that

The relationship between land, waters, trees, rocks, animals, birds, fish, insects and other things and humans is deeply embedded in language, stories, values, ethics and social institutions. This is a completely different concept than ascribing human characteristics on to animals and plants. It is not about humanizing the non-human but recognizing the agency of non-human entities for their own characteristics.

Taupaki uses whenua collected from her awa—Waihou—to weigh down the stacks of paper in this exhibition. Waihou is a living entity that has been historically degraded through the Mining Act of 1891, another piece of legislation that Taupaki riffs off of. The land and awa have been exploited by these Acts, with long-lasting effects for the uri of Ngāti Hako who espouse the whakataukī ko au te awa, ko awa te au. I am the river, the river is me.

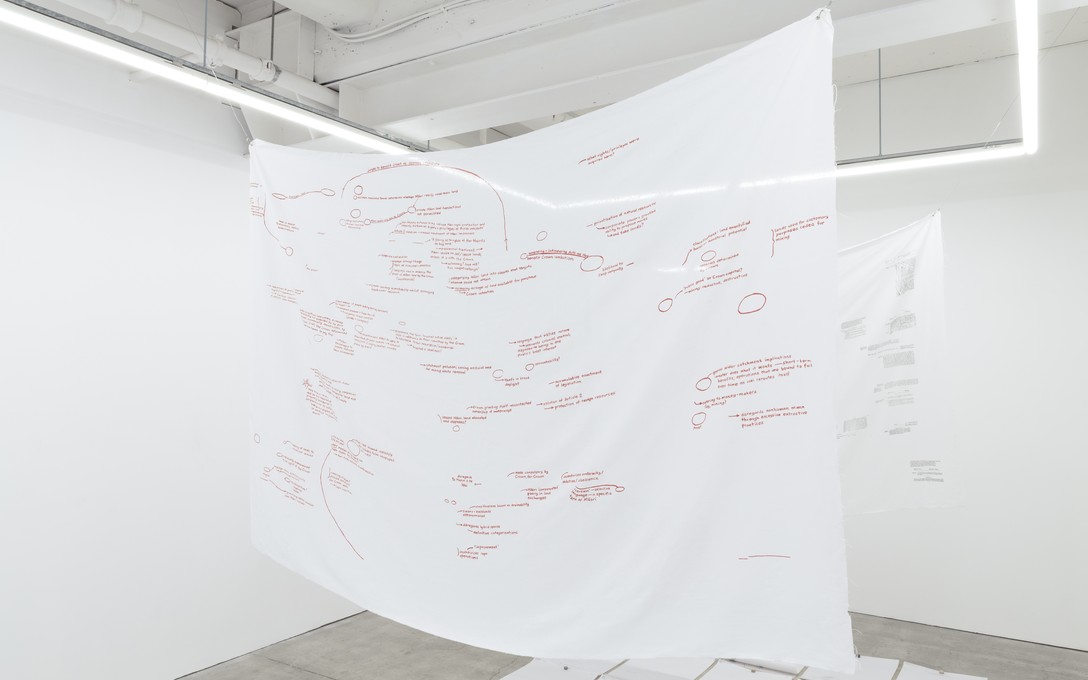

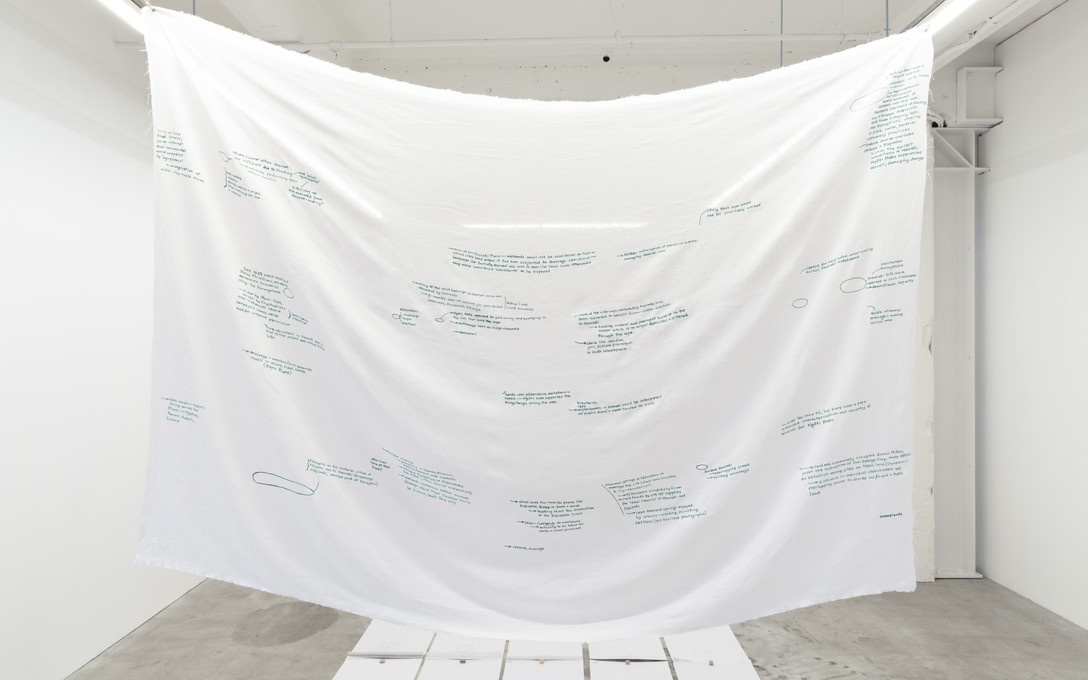

In the past, Taupaki’s research has been the backbone of her exhibitions; integral, yet often unseen. Here, she lets the research become the exhibition. Taupaki’s time spent in libraries and archives reading, scanning, highlighting and annotating are reflected in the fifty sets of four layered drawings placed in the gallery. Three sizable mind maps unfurl from the ceiling, a large-scale representation of the artist’s documentation on display. This exhibition is the culmination of years of mahi tahi. A residency at Te Whare Hera in 2022 allowed the artist to spend time in Archives New Zealand, providing a starting point for a project focused on the use of language as a colonial weapon that perpetuates violence against Māori. While in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Taupaki also exhibited with Jhana Millers Gallery in a show concerned with fostering a connection to te taiao through the use of local natural materials.

Wānanga and fieldwork play an imperative role in Taupaki’s work. She has engaged with mana whenua in recent public programmes in Tāmaki Makaurau with Samoa House Library and in Tūranganui-a-Kiwa with HOEA! As a part of this exhibition, Taupaki will lead a community workshop to foster relationality and reciprocity. Enjoy is proud to present All This Work Is Necessary during this period of time in Aotearoa.

Past Event

Walking and Mapping Kumutoto Stream with Ashleigh Taupaki

At 10am on Saturday 3 February, the last day of Ashleigh Taupaki’s exhibition All This Work Is Necessary, join the artist for refreshments at Enjoy Contemporary Art Space and kōrero about the kaupapa before we begin our walk along the Kumutoto stream.

More info

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, All This Work Is Necessary, 2023. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Map Layers 1 - 200, 2022-23, pen on tracing paper, rocks from Hauraki waterways. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Acts, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Annotations, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Hauraki Annotations, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, All This Work Is Necessary, 2023. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Acts, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Annotations, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Hauraki Annotations, 2023, pen on linen. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ashleigh Taupaki (Ngāti Hako, Samoan) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau, working primarily in object, drawing, and research practices. Systems of power are interrogated through iwi and place-specific narratives; with decolonial methodologies embedded in the material processes, and collection of stories and knowledge. Using found, gifted, and natural materials, Taupaki has developed an expanded mind mapping practice that emphasises connectivities within social, cultural and environmental ecologies. Through community workshopping, Taupaki uses this mode of engagement to offer a sense of place and material agency to those outside of the institutional academic space in a way that fosters sharing, relationality and generosity.

GLOSSARY

Awa — river

Kahikatea — a tall coniferous tree of mainly swampy ground

Mahinga kai — traditional food-gathering place

Mahi tahi — working together

Mana whenua — Māori who have historic and territorial rights over their tribal land

Pūrākau — myth, legend, story

Raranga — weaving

Rongoā — remedy, medicine

Te taiao — the environment

Tūpuna — ancestors

Tūrangawaewae — place where one has rights of residence and belonging

Waiata — song

Wānanga — educational meeting, seminar

Whakairo — carving

Whakapapa — genealogy

Whakataukī — proverb, significant saying