Enjoy

Blog

Contents

Reading The Stones Talk

July 06 2022, by Liang Cui

It is usually taken for granted by museum visitors that archaeological objects are chronologically displayed according to certain scientific classifications. These methodologies serve a continuous historical narrative, either to promote simplified Darwinian evolution of humanity from primitive to modern, or patriotic sentiments. This methodology also guides the selection of the objects to be exhibited. Yet this leaves us with a rarely asked question—how about objects which cannot be integrated into the museum’s story, and thus are rendered as ‘others,’ by current museology?

The Stones Talk, ed. İlkay Baliç (Istanbul: ARTER Press, 2013).

The exhibition The Stones Talk by artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu held in 2013 at Arter Contemporary Art Museum in Turkey engages with ‘unwanted’ archaeological artefacts. Often fragments, considered lacking in aesthetic and evidentiary importance, they are referred to as “study pieces” by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Turkey, and are preserved for archaeological research rather than museum display. The artist reproduced 71 such pieces from different excavation sites in Turkey. Combining the replicas with other materials, such as ceramic with brass, and iron with glass, she instals the ‘new’ created objects in an arbitrary manner, following no obvious rule.

Aslı Çavuşoğlu, The Stones Talk, 2013, ARTER Contemporary Art Museum. Left to right: No. 27. Glass, iron. 8 x 11 x 23.5 cm; No. 29. Wood, mosaic. 25 x 25 x 4 cm; No. 44. Brass, ceramic. 16 x 10 x 8 cm. (Each word set in bold indicates the material of the study piece). Images scanned from The Stones Talk, ed. İlkay Baliç (Istanbul: ARTER Press, 2013).

Without seeing it in person, I encountered The Stones Talk through its homonymous book in Enjoy Contemporary Art Space. The book is dual language—English with Turkish translation for the first half, and Turkish with English translation the second—and consists of four essays about the exhibition, images of objects selected from the exhibition, and drawings of the 71 study pieces. It may be widely agreed that the experience of reading a book about art can be quite like experiencing a piece of artwork, (and many other books too), which is exactly how I felt after the reading.

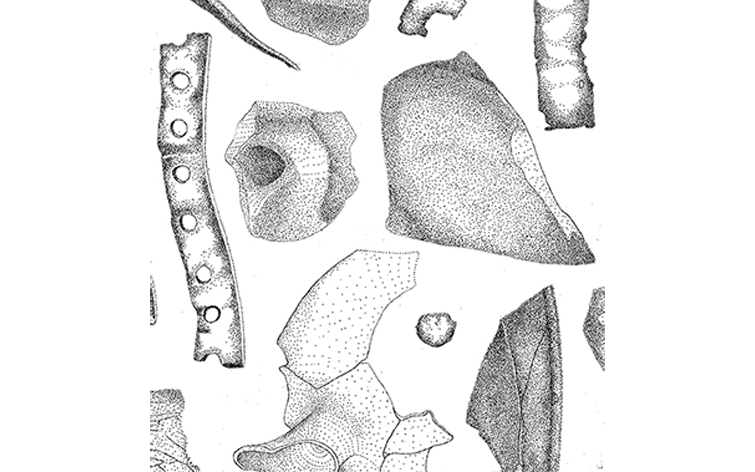

In the book’s introductory essay Özge Ersoy describes Çavuşoğlu’s artworks forming ‘unexpected shapes and associations that are free from references to everyday objects.’ arguing this method leads to “performative interpretations,” since the ambiguity invalidates any effort of making a persuasive story out of it.1 The book itself embodies these objects’ ambiguity. Physically, it is neither big nor heavy and is comfortable to hold. With drawings of several irregular shapes like a collection of unknown sea creatures, its pliable, titanium white cover conveys an impression between humbleness and indifference. Glancing through the pages, I indulged myself in the insights presented by the essays and savoured the anecdotes, building and deepening my distant experience of the work. The main section of the book, the drawings of the 71 “study pieces,” is what I would like to discuss, sharing my thoughts inspired by it.

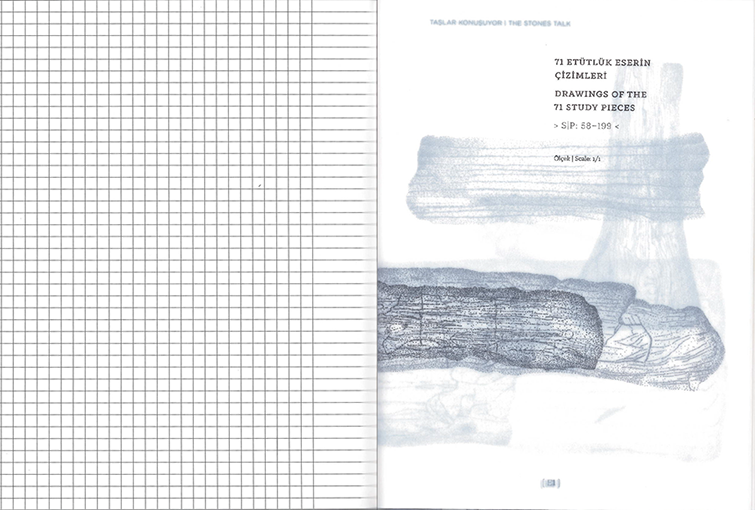

Scanned image from The Stones Talk of its first page of “Drawings of the 71 Study Pieces”.

These drawings are confined, bookended by two pages patterned with a grid, like the grids used to determine locations of artefacts in archaeological sites. Upon close inspection, the drawings of these study pieces are formed by a delicate arrangement of dots, therefore not a single line is defined, as if these objects are still becoming. The scrupulous depiction of detail makes it easy to perceive a trace of intimacy. Imagining the drawing process, the eyes need to ‘touch’ the whole surface of the object, carefully examining every wood grain, every slight dent on the metal pieces, and every gentle curve of the ceramic shards. Yet, the meticulous nature of these drawings also reveals a hint of restraint, we can hardly sense any emotions although the drawings proceed in such intimate contact with the objects.

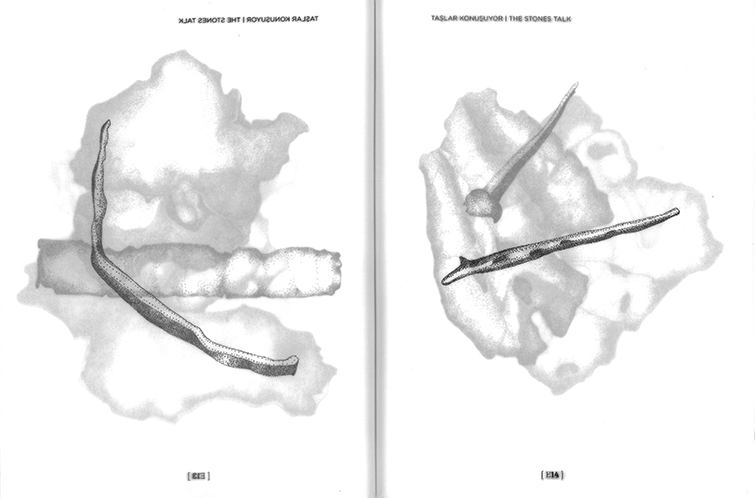

Within the book the drawings are printed on sulfuric acid paper, the translucence of which allows a glimpse of what’s underneath. Flipping back and forth is like viewing several archaeological strata together from any single page, reviving my memory of reading about Husserl’s inner time-consciousness. The primal constitutive source of our experience as human beings, it is different from the time our post-industrial clock presents to us with discernible ‘gaps’ inserted between each click. For inner time-consciousness, time is liquid. It is a river, with no discernible division between sections considered as the past, the present, and the future.2 And so, we inherently seek for continuity. Among these pages, while the present page is clearest, and others gradually fade away, the present is saturated in its past, and gradually dissolves into its future.

Scanned image from The Stones Talk of its translucent pages of “Drawings of the 71 Study Pieces”.

These layered drawings traverse the object on the present page or merge with each other to form a ‘new’ object. I realised, when looking through these translucent pages, that I constantly tried to make sense out of these objects entangled with each other, detecting their affinities and making up connections, since meanings usually emerge in a pattern when grouping things together. Yet, the ambiguity permeating these pages proves too generous for my endeavour. It seems feasible to interpret the forms from diverse disciplines, while none of these interpretations would exclude other possibilities. These objects resist being pigeonholed in any prescribed narrative. They are not reducible to a rational system used by us to interpret them, to endow them meanings. As the title The Stones Talk implies, they tell stories themselves. Sensing this gesture of autonomy, the otherness filtered out of yet constantly lingering outside othordox history’s narratives, became suddenly palpable for me.

Here, I perceived an effect of the displayed continuity enabled by the structure of the book and its use of translucent paper—it fits our inner sense of time. This familiarity, so cosy to nestle in, encourages us to engage with these “study pieces” through our own experience of the narratives that we are tuned to. The comfort, in turn, weighs on the strangeness of the moment when otherness presents, which may shake what has been petrified in us by the ubiquitous institutional discourse, and thus open us up to an alternative.

-

1.

Özge Erosy, “The Stones Talk” in The Stones Talk, ed. İlkay Baliç (Istanbul: ARTER Press, 2013), 15.

-

2.

The first time I encountered Edmund Husserl’s idea of inner time-consciousness was in his Logical Investigations. I cannot remember exactly which version I read at the time, since it was several years ago. However, I can vividly recall how I was moved by his insights. Huserl’s further development of this concept can be found in The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness.