Exhibition Essays

Awoken Anew

June 2024

Awoken Anew

Brooke Pou

Ko te mauri he mea huna ki te moana

The mauri is hidden in the sea

At a recent wānanga for Māori curators, kōrero on Ō-Tāwhao marae reminded me that in addition to te reo Māori, our reo was also taken from us in the forms of reo whakairo and reo raranga. These oral and visual languages that tangata whenua were once fluent in were almost lost and it is only through perseverance that we can reclaim them. Heidi Brickell understands well what this is like, having studied the languages of her tūpuna in order to connect with them and reconcile their world with her own. The materials she uses in her exhibition at Enjoy are an exploration of the relationship between Tangaroa and Tāne Mahuta—atua of the sea and forest—who still maintain a lot of influence in our lives. Through her practice, Brickell reinforces her bonds to her tūpuna, te taiao and Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa.

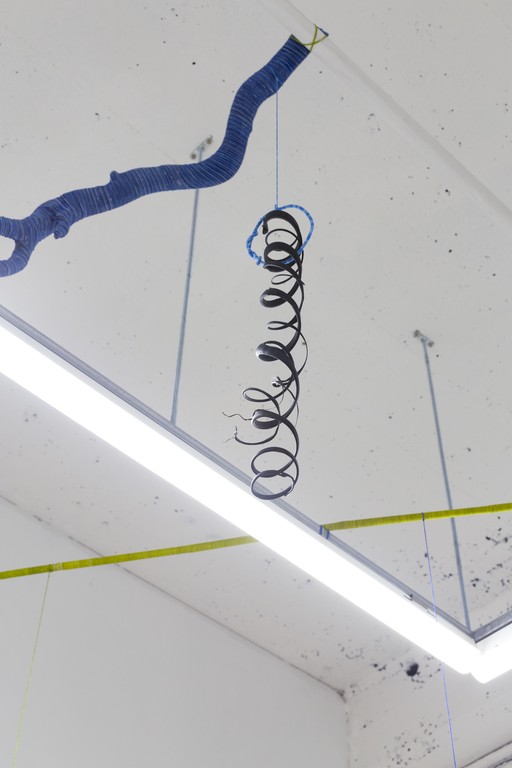

Heidi Brickell, A koru is a trajectory, 2024, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Brickell has collaborated with the whenua, moana and ngā atua Māori in the creation of all works in A koru is a trajectory. Rākau from Ōtaki sanded by Tangaroa has been lovingly twined with hand dyed cotton in varying shades of blue, green and purple, resulting in contorted sculptural forms that embody the relationship between sea and land. This is an expansion upon her painting practice that similarly utilises cotton thread carefully positioned atop the canvas. It is also connected to the pūrākau of whakairo being from Tangaroa and brought to land by Ruatepukepuke. Today, there are steadily growing numbers of wāhine Māori practicing whakairo, however Brickell does not do so in the customary sense; instead bridging whakairo and raranga by wrapping each rākau two threads at a time. Rimurapa that has washed ashore Te Raekaihau has been taken into the artist's care and warped to reflect its tumultuous journey from the moana to the whenua, much like tūpuna Māori who navigated Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. Their haerenga to Aotearoa is of interest to Brickell, who has been researching her tūpuna, including the legendary Kupe, while contemplating their psychological mindsets as they traversed the world's largest ocean.

Heidi Brickell, A koru is a trajectory, 2024, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Studies about contemporary oceanic voyaging make it clear that mental fortitude is just as important as physical strength when faced with the might of Tangaroa. A first hand account from Benjamin B.C. Young describes how physical dangers such as “high winds, huge waves, fierce tropical storms, monotonous days at sea, and blistering effects of the equatorial sun”1 impact voyagers’ mental well-being. He discusses feelings of anger, depression and irritation while aboard the waka. Young goes on to express his admiration at “how our ancestors were able to journey across the Pacific and still face the effects of long voyages.”2 In a qualitative study into the insights of experienced voyagers, researchers found that they were “mindful of the expansiveness and constantly changing power of nature while at sea”, resulting in “a reciprocal rhythm with their environment and each other.”3 Reciprocal rhythms between tangata and the Moana are the reason Māori are here today and bring to mind a term Brickell has spoken of called ngā kare-ā-roto, referring to the waves within us. These waves within are, according to Leonie Pihama, “the physical and spiritual manifestations of how we understand and feel emotions.”4 Brickell is not afraid to feel and harness her emotions when making art. In fact, during a kōrero we had last month she used the phrase “anger is a trajectory.” Indeed, anger is a powerful emotion that can drive all kinds of projects, including sailing across the ocean.

Heidi Brickell, A koru is a trajectory, 2024, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

The moana is a highway for people of the Pacific. Academic Epeli Hau’ofa posited the idea of the ocean being a way for us to connect instead of an impediment we need to overcome. Viewing the moana as “a sea of islands” rather than “islands in the sea”5 radically alters our relationship to this place by emphasising the importance of the ocean as our home. Making art out of materials gifted to her by the moana directly addresses the standings of ngā atua Māori, one of whom (Tangaroa) Brickell feels “has been relatively put to sleep” 6 since our tūpuna settled in Aotearoa. Brickell’s initial plans for the Rita Angus residency naturally evolved in response to what she calls “the physical and emotional experiences of late capitalist environmental crises and economic cruelty that were crashing down”7 while she was at the cottage. During this period, Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau experienced unprecedented flooding and Cyclone Gabrielle tore across Te Ika-a-Māui. Our own ill-preparation and the affected areas governing bodies’ insipid response show just how disconnected from the natural world we have become. According to some iwi—including the artist’s own Ngāti Kahungunu—the atua of the ocean and his brother Tāwhirimātea (atua of the winds) have been in conflict since Tāne separated their parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Tāwhiri is exceptionally resentful of the separation and expresses his anger through his control over the weather, demonstrating his wrath through extreme storms that negatively impact Tāne’s domain. During the making of this exhibition, Brickell has explored pūrākau, pūmanawa and mātauranga in an attempt to centre herself during an incredibly chaotic time that she likens to “navigating an ocean somewhat blindly in response mode.”8

Heidi Brickell, A koru is a trajectory, 2024, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

The artworks that were produced in this response mode are spirals, anthropomorphic forms and twisted masses. They vary in colour and size and are installed at different heights around the room, suspended from the ceiling. Some are also encircled in twined wire, while others have straight rods piercing right through them. Kōhatu and smaller rākau connected to certain works are grounded on the gallery floor through the use of vertical threads. Most feature koru. Koru are the defining motif of toi Māori. Much more than symbolising new life, Brickell considers how the koru form that pervades mātauranga Māori is the fundamental shape of physics that the body comes to learn how to weather. This is an installation that makes many manuhiri hyper aware of their own bodies. Tendrils from the centrepiece, Muturangi Vortex, literally reach out and catch my hair as I walk through the space if I’m not careful. At times, works Brickell has moulded into an ideal shape seem to have grown a mind of their own and warped the way they want to. The rimurapa that she works with has important ecological functions including feeding and housing marine life and cooling the ocean. Arranged in sequences that allow for viewers to weave in between artworks, the artist has transformed the gallery to reflect the rimurapa ngahere in the moana that are steadily declining. The state of rimurapa in the moana is linked to that of rākau on land. New Zealand Geographic writer Bill Morris asserts that,

Once, the forests in New Zealand’s ocean were mirrored by lush forests on shore. When those trees were felled, soils began eroding. Since World War II, the intensification of farming—and its expansion into more marginal areas of hill country—has increased the amount of sediment running into the ocean.9

This pollution causes a lack of light in the ocean, adversely affecting rimurapa’s ability to reproduce and photosynthesise. It is just one ripple in the tidal wave of problems our moana faces.

Heidi Brickell, A koru is a trajectory, 2024, installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

A koru is a trajectory is an exhibition of artworks that were once living forms. Through a physically and emotionally labour intensive process they have come to exist in a liminal state. Rimurapa and rākau live on, albeit in a very different way, at Enjoy.

-

1.

Benjamin B.C. Young, M.D, “Psychological Effects of Long Ocean Voyages” in Hawaiian Voyaging Traditions, https://archive.hokulea.com/ike/canoe_living/effects.html.

-

2.

Ibid.

-

3.

Marjorie K. Leimomi Mala Mau et al, “Exploring Perspectives and Insights of Experienced Voyagers on Human Health and Polynesian Oceanic Voyaging: A Qualitative Study” in PloS One 19, no. 4 (Spring 2024): 16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296820.

-

4.

Leonie Pihama, Hineitimoana Greensill, Hōri Manuirirangi and Naomi Simmonds, He Kare-ā-roto: A selection of Whakataukī related to Māori emotions (Hamilton: Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019), iii.

-

5.

Epeli Hau’ofa, “Our Sea of Islands”, in The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1, (Spring 1994): 152.

-

6.

Heidi Brickell, email message to author, April 13, 2024.

-

7.

Ibid.

-

8.

Ibid.

-

9.

Bill Morris, “The Kelp”, in New Zealand Geographic issue 176 (July-August: 2022).