Exhibition Essays

Adventures in Making and Relating

February 2021

Adventures in Making and Relating

Xin Cheng

Seeing

A clear glass bottle with “Made in Taiwan” embossed on the bottom. Looking through: blue, bright sunshine, white. Seagulls screeching, waves crashing, crisp sounds of sand or pebbles squashed under footsteps. Moving shadows. Bits of green, then light and blue again. Reminds me of a kaleidoscope. What is a kaleidoscope, a lens for seeing the world around us?

Bena Jackson and Teresa Collins, Bottle's life, digital video, stills, 2021. Image courtesy of the artists.

Journeys & Transforming

Walking with Teresa and Bena, the gutter and sidewalk become a treasure hunt. Surprise findings of traces, mysteries of the city, the other dwellers. Passing by posters. While the visual communication designers and marketers are busy luring everyone's attention with their shiny billboards and golden ratios placed at perfect eye level, Teresa and Bena have trained themselves to attend to another world: small stories, local memories, the weirdness and wonders of leftover materials and pet cemeteries.

A tin shed roof covered with brown leaves, surrounded by karo1 bush. Half of a wood-framed chair on the right, its upholstery mostly gone, except for a blue quilt-matting attached on one corner. To the left a coil of wire netting. We move into it, curious what the view would be like from the middle of it. Swiftly we hover out of the coil. A sense of relief: back on safe ground. Was that a cat's eye view?

In the gallery toilet, I found the same coil of wire transformed into a basket, holding spare toilet rolls.

“…the bins are full of stories”

“…this is the pet cemetery... I've lived here for so long, there have been many beloved pets...”

“We started making stories between people and objects.”

I have been mending a pair of brown pants this afternoon. A few months ago, I found a rip on the bum. Did I sit somewhere, or did it rip when I jumped a fence to get to the creek? The brown pants are the ones I found in a free-shelf near the apartment where I lived in Hamburg.

This is a world where the exchange value of material things no longer matters. Maybe not their use value either. Objects as carriers of stories, recombined to make new stories.

Bena Jackson and Teresa Collins, Luxurious economy, digital video, stills, 2021. Image courtesy of the artists.

Care & Craft

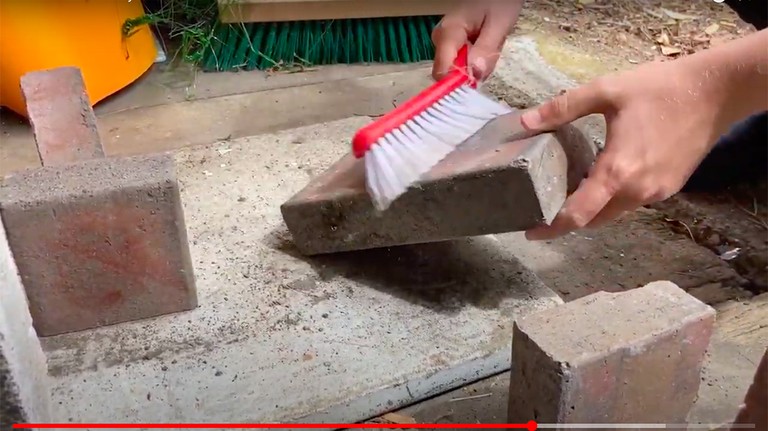

A scatter of bricks on concrete ground, perhaps next to a shed or studio. A hand comes along, caressing. Then a brush, the kind that we use with a shovel. Resonating sounds, crisp and hollow, as the bricks scrape against the concrete base. Rhythmic song. Bits of dust and concrete shed off the brick. A triangular brick emerges, clean and shiny as if reborn. “Pretty good!” a satisfied voice.

I once saw a saw-horse in a mountain village in Italy, a bent tree trunk with two leg-sticks added to stand upright. At one point in time, the act of making began with a walk in the woods, looking for a branch of the right shape, as opposed to going to your local hardware store.

After living on a trash mountain in Seoul, I could no longer bear the thought of making artworks which ultimately add to the mountains of trash.

Bena Jackson and Teresa Collins, Luxurious economy, digital video, still, 2021. Image courtesy of the artists.

Uncovering stories, crossing paths

A room where every single thing has a story, many stories. Where each of the components came from, the person who handed each object over, the conversations and encounters, how the artists had carried some of them around in their daily lives, how the things were modified by hand or joined together with some other stuff, where the things might go after the show, where they had gone.

Since I was invited to write, I talked with the artists as they prepared for the show, and at the gallery. So I can tell you stories a normal audience would not have gleaned.

Objects carry secrets. I do not know whose hands touched the keyboard I am typing on, before it got into its designed packaging; nor am I aware of the exact location where the minerals once lay, before they were extracted into aluminium keyboard frames. Anna Tsing wrote about this as the alienation of capitalism. However, in following the trail of the matsutake mushroom, she also uncovered many instances where “unalienation” happened between the forest and the dining table, where new meanings and personal relationships are nurtured, through the exchange and passing on of the mushroom.2

In the gallery, I remember the gleam in Bena’s eyes as she talked about finding shattered mirrors embedded in asphalt on the side of the road. That knowledge changed my own reading of the object: being able to distinguish what was found and what was made by the artists.

Tim Ingold, the anthropologist, wrote about making as a form of corresponding between hands and matter. Finding things/matter/half-objects and transforming them into something else. Hands moulding matter, matter changing hands. Between art, architecture, and anthropology, matter is always transforming, always becoming something else.3 I wanted to write that the exception is art works in permanent collections. But then I recalled the effort of conservators to reverse the process of decay, and a strange memory from several winters ago, when I visited the Dieter Roth Museum in Hamburg, all the chocolate bunnies lined up in acrylic vitrines, teeming with borer beetles, in various states of weathering.

Ingold used the example of clay and brick-making, a traditional “craft” medium. It is not only the potter imposing their will, the potter’s hands also follow the lay lines of the specific clay.4 Push and pull. To and fro. In a similar way, Bena and Teresa have corresponded with the things, people and stories that answered their call out, and their search. The “artworks” are imbued with specific and quirky encounters, and new meanings and attachments are formed to particular things.

A stuffed panda hanging over the dashboard of a car, on an uphill journey. Sceneries change.

These are small stories, from people whom you may have sat next to on the bus, whose yard you had driven past, from whom you may have bought coffee, with whom you may never cross paths. Here grow personal attachments to things, recreating imagery from memory, forming new associations. Instead of going through the usual channels for obtaining art materials, the artists embarked on an adventure in their local surroundings: calling out for surplus and unwanted materials, not asking for anything specific, curious to see what comes along. Bound in secret knots as I think about it now–sitting in the communal kitchen in an acupuncture school in Auckland–offered snippets of a process, an adventure Bena and Teresa embarked on, through which they encountered people and played with unexpected finds. Art-making thus became a way of navigating the living world around us, a conduit to reach out to people otherwise unconnected, while being open to distractions and interruptions, changing the direction one had set out to take...

A cat roaming the neighbourhood...

Bena Jackson and Teresa Collins, Luxurious economy, digital video, still, 2021. Image courtesy of the artists.

Local know-how

“...if you ever need plastic buckets, ask the Seashore Cabaret in Petone. They have a constant supply of them for sour cream and so on.”

I've been designing a small document–“distributed resource centre”5–for my friend Chris Berthelsen. He's been discovering places to get free resources for making around his neighbourhood, and making new things out of them with other people. Foraging is deciding to open our eyes to the abundance that is right around us. The abundance leads to a sense of generosity, of sharing the know-how, and convivial enjoyment.

Look down the back alleys and skips, you can discover all sorts of stuff waiting to be transformed and enjoyed.

Bena Jackson and Teresa Collins, Luxurious economy, digital video, still, 2021. Image courtesy of the artists.

A dream

What does it look like, when objects are liberated from utilitarian functions, becoming relational objects between people who would otherwise not cross paths? What happens, when artists are liberated from having to produce art works in galleries, and instead act as facilitators in generating new ways of relating with our material surroundings?

I had a dream that Enjoy stopped paying for inner-city commercial rent, instead operating from unoccupied garages in the suburbs. Something a bit like Paludal art space in Ōtautahi, but more itinerant. The project is called Open Home. Bena and Teresa have their works in one of these cleaned-up garages with white and brick walls. The same objects from Bound in secret knots are on the walls and scattered in the space, and in the corner is a table with tea and snacks. Bena and Teresa sit there and talk to whoever comes by. They host weekly reading groups and making sessions. People bring in stuff, and they transform together. They record new videos and stories and make new things, which over time replace the original works on the walls. It runs every weekend for an entire year.

-

1.

Pittosporum crassifolium

-

2.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Oxford; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015),121-130.

-

3.

Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (London; New York: Routledge, 2013)

-

4.

Ingold, Making, 101.

-

5.

Mairangi Arts Centre, distributed resource centre (Auckland: Mairangi Arts Centre, 2021), http://small-workshop.info/doc/drc.pdf