Exhibition Essays

Kōrerotanga. Listen, watch, carry the days...

April 2021

Kōrerotanga. Listen, watch, carry the days...

Brook Konia

Here I am, having rounded the inside corner to the back room of Enjoy Contemporary Art Space. I am sitting among dark grey painted walls. There is a projector set to display on the far end wall. Set up as the cinematic experience.

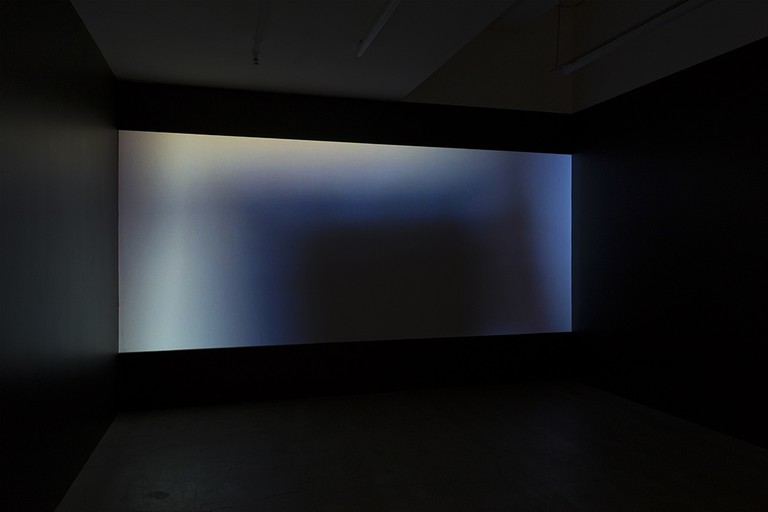

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

“Over the years the camera becomes like a friend, something you learn to take with pride into places of great power and the humblest of villages. Yet which of us is not anxious walking with a friend into a new world?”1

Barry Barclay considers the camera a friend. From his many critical reviews of the works he had made, Our Own Image became Barclay’s published collection of thoughts on how he came to reason with his chosen medium. This succinct ninety-eight page book describes Barclay’s perspectives, thoughts and experiences; within his career as a Māori film maker in Māori film discussing Māori New Zealand intersectional histories, and production work on national and internationally requested documentaries. The collection initially came to paper during his international success with the film Ngati (1986). Tracking through international film festivals and the post-screening chats with audiences Barclay responded to probing questions on the role of Indigenous communicators with ‘on our feet’ responses. In the first chapter “A Fitting Companion”, he contrasts linear film making—its assertive answer-seeking—with the building up of getting to know someone, the love of contact through talk in Māori life, time spent with someone and the beauty in talking from the heart. I reflect on this text to consolidate the research skills of patience and listening being rewarded with respect and connection, and make it the door to walk through for this response to He waiata aroha, the eight-minute long art film created by James Tapsell-Kururangi that speaks of his loved memories for his kuia and great-grandad.

***

He waiata aroha is a conscientious artwork in its conception, creation, and also delivery. Tapsell-Kururangi's work takes hold of the camera (Sony Alpha7 III mirrorless full frame digital) and guides us through an obscurely captured luminous world of bleating pale colours pitched in a mode of blinking between two sites; the domestic suburb and an evening spent outside. On this journey, we hear from Tamanui te Rā the Sun and his yearning for freedom from the bindings that Māui and his brothers caught him in.

All is quiet for the first few seconds.

A formally-spoken low-toned voice speaks in te reo Māori, wavering through the speakers, accompanied on screen by white font English text.

“Ko ngā mōrehu ēnei. Ko ngā koiwi, ngā kaupeka rānei, kua mahue mai. He awa te rite e pupuri mātauranga ana. Ko au kei te whakarongo, kei te mātakitaki, ko au ka kawe i ngā rangi.” “What remains, bones, limbs, the river runs thick with knowledge. I listen, watch, carry the days.”

These dual language devices introduce us to an omniscient being, upset, maddened and alone. The wall lights up with the short-lapsed capture of riverside grass. The first visual that beams onto the wall is a close-up of tall rush grass. Before it is over, a spider is briefly visible crawling from under one of the blades. It just begins to walk along its web as the screen cuts to black again.

The orator's voice talks to us, shifting from first-person singular to we. “Ko mātau kei te Makariri...” “We are cold and our bones ache, starved of your warmth. It has been dark for far too long. Slow down!” We hear the rebuttal of Māui and his brothers for Tamanui te Rā to stay in the sky.

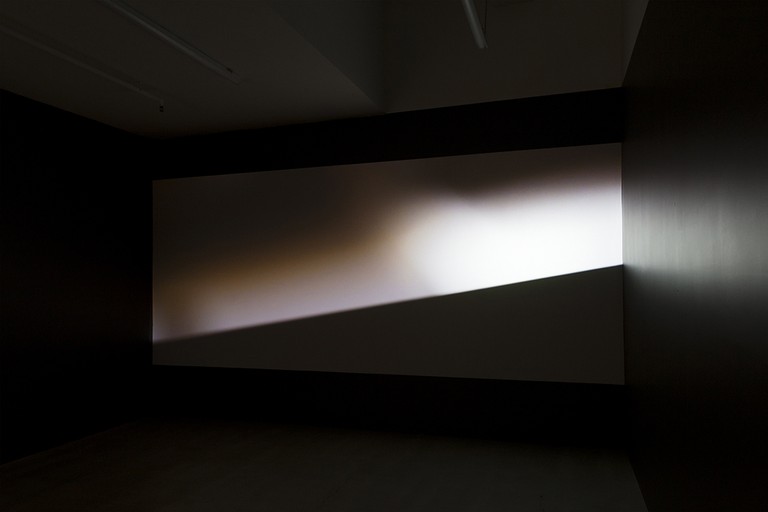

A melodious light with tones of beige and wooden brown appears. It moves gently, and the voice of the omni-being is back, identified by deduction as Tamanui te Rā. “Why did you tie me as your slave? Held in bondage.” A window looking to the outside is now in focus; a clear sunny day is visible. A small dining table is seen angled from an obscured looking-down perspective, the kind of head tilt you make when you sigh "carry your pain and suffering and your hopes, dreams, love".

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown

The brief scenes are dressed with lengths of captured light; rangatiratanga emanates from within it. The movement of light symbolises an active ancestral presence. Peter Gossage's writing of Māui Slowing Down the Sun tells us, "the sun drifted slowly began to creep across the sky… and if you look hard you can sometimes see the [magic ropes] that bind the sun to the earth".2 In this passage Gossage offers light rays of the sun as pāraharaha and tuamaka (woven ropes) binding Tamanui te Rā to the earth as mentioned in oral history.

Our human eyes see through tears (sad and joyful) in a hazy way. The maybes and probably-s of figuring out what objects were filmed for the emanating light is not the point of this artwork. Abstractly filming light splashed with blurry tones, curving brownish lines. It cuts to dark again; the voice tells us it is alone in the dark. Pain suffering hopes dreams love.

Laments for freedom by Te Rā are painted with the light of these two spaces to describe Tapsell-Kururangi’s own grief and love. The camera isn't set for documenting: we the viewer are to read the light differently as we are transported into the wānanga with the sun and the river. Rangihiroa Panoho notes the luminosity recorded in watercolour by 19th-century surveyors communicating the qualities they saw in the landscape of Aotearoa.3 Speaking primarily in the language of Tamanui te Rā, Tapsell-Kururangi takes back this luminosity. Here we can discern the heart of the artwork, the dappled light, the shimmer of our rivers.

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

The grass from the beginning scene reappears. Te Rā speaks "I have carried and given life to the forests and watched you rise at morning to grow old. I have studied the river. The way the currents pull you together". Tapsell-Kururangi found comfort being in these spaces, in the afternoon sun’s warmth, the cool refreshing walk at the water's edge.

Shots of blurred light twinkle. Hazy white and light browns and yellows.

I am quiet with heightened attentiveness. My breath slows to listen to waiata. A low voice wraps around honed, lingering vowels and dullen consonants to the rhythm of “He Waiata Aroha”. A song of the sky and the river, above, below and beyond. Here is where Tapsell-Kururangi bares his heart for us. The song offers the opportunity to draw near the realm where his grief and love sit. A dark square—an opening—emanates on the screen. Shifting, our eyes wade through brown and blue. The subtitles do not come for this outro. The voice gains reverb and is joined by the sound of an amplified river, trickling as if to seek harmony. The grass appears again. A long fade out to a purple evening light. Silence. Cut to black.

In its final mode, the waiata is an emotional surrender at the river. An embrace by Te Rā who carries pain, suffering, hopes, dreams and love. He sees how the river pulls Tapsell-Kururangi together to his whakapapa, the stories and histories he heard from his kuia. The same blades of grass whimper—yet no longer tethered by the work of the spider. Simply beneath the sky and by the river.

***

Tapsell-Kururangi's kuia tells him the story of her father's death in the Tongariro River, a moment that has him return to the river many times, a ritual of asking the universe what it all means. A crux of his own life, his returns have been peppered between studying and graduating from Massey University, spending a year living in the home of his kuia, and the most recent of ventures, moving to Tāmaki.

Each element in the world tells a story about its story to another. Winds, trees birds, wildlife. These intimate stories can be found within pūrākau, oral histories, in waiata. The sun’s light warms us, awakens us. It dances with the environment. The grass grows at the edge, kissed and nurtured when near water. The parts we play as humans are all part of these stories too.

In understanding an art form, you need to understand the landscape that comprises its environment. The histories that human beings have imbued into these places; all of these landscapes are part of a tapestry of human connection. Memories endemically hold essential parts of our identity and how we recall and retrace life, how we return home. Tīpuna read the signs within the world to guide them. Thus, we should share an awareness of the place where we live.

Back and forth between the river and the house, between blinks of voided projection. He waiata aroha does not measure distance. Here in this room, both places and histories told are one. We glimpse abstracted angles, blurred visuals and discuss what Tamanui te Rā tells us each time we see them—remembering histories by the twinkle of light over water. There are many stories at the river, but this is the story of James and his whānau.

Conscientious, Tapsell-Kururangi’s art practice calls to death, for it is death that has brought him here. However, it is also life. He is recounting stories of his great-grandad. This is not a labelled image of the river. The camera as a tool of capturing light brings the voice of the landscape forward. It lets us see and hear how this place is speaking to Tapsell-Kururangi.

***

"How can we take that maverick yet fond friend of ours the camera into the Māori community and be confident it will act with dignity?"4

The camera user knows they hold all future viewers to the place they stand inside. Barry Barclay called it the hui for his production work. "The process involves humility, the humility to bend the technology to the rules of the hui - to allow everyone present to speak".5 How can we remain tika on technology as it launches ahead in its exponential force to be the centre part of the everyday? Tapsell-Kururangi’s humility is in seeking mentorship and guidance over his camera work, spoken words, text and composed waiata, working with his mother, his artist-mentor Shannon Te Ao and te reo Māori translator Ngaere Roberts.

Tapsell-Kururangi's use of painted light, of waiata within his artwork grows our understanding and ability to connect even more so to the earth we stand on, the universe we are a part of. His art is an extension of how he has determined and navigated his being, and it shares his love for his family. We all as individuals navigate love, grief, the great emotional human experience. It pertains to all of us—with hope, the opportunity to imbue meaning to the world.

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ka mua ka muri—longing, not for the past, nor the future. Rather it is our particular way of deeply viewing the world, embracing and seeing what has gone before and finding clarity for what is ahead. Māori oral histories are expansive, offering greater cosmic awareness of who we are. All the stories around us, the landscapes, our whānau, our mentors; we stand tall on many Indigenous photographers and filmmakers that have lead the way with cameras. It all becomes the trusted wānanga that establishes meaning and gives validation.

Tapsell-Kururangi's status of emotions is steered by his oral histories taonga tuku iho; treasures passed down. Confident with the camera, He waiata aroha reveals a love of whakapapa shared to us through the application of cinema in an art exhibition space. The interplay of space and outcast light. The installation becomes a sensory organ, and it leads us as we hear the story. I handed over my eyes and ears to Tapsell-Kururangi for him to share a story with me. I think this is the most reassuring part of his storytelling. He defines his grief, love, self-love, and love for his family. He trials making sense of the world—in languages of the cosmos.

I invite all to come and watch.

-

1.

Barry Barclay, Our Own Image (Auckland: Longman Paul, 1990), 9.

-

2.

Peter Gossage, Māui and other Māori Legends: 8 Classic Tales of Aotearoa (Auckland: Puffin, 2016), 108.

-

3.

Rangihiroa Panoho, Māori art: history, architecture, landscape and theory (Auckland: Bateman, 2015), 30.

-

4.

Barclay, Our Own Image, 9.

-

5.

Barclay, Our Own Image, 13.