Exhibition Essays

I live my life in widening circles

June 2022

I live my life in widening circles

Beth Harris

On Blushing moves within the intangible space of eros. Elements of longing, grief, beauty, terror, ambiguity and light are offered to us in art works by Alice Langbrown, Dayle Palfreyman, Steph Arrowsmith and Willa Smart.

The new works in this group show are partially inspired by Eros the Bittersweet Anne Carson’s exploration of desire in philosophy and literature.1 Carson’s work has been a thread of intrigue responsible for many creative conversations throughout my friendship with Tom Denize (the curator of this show), since I recommended Autobiography of Red 2 to him in 2018. I’d never read a novel in verse before and the novelty of the structure, as well as a coming of age love story that took mythical figures into a high school context, was magical. I felt the complexity of the narrative echoed the friendship we were developing. Young and curious and concerned with language and beauty, Tom and I fell in love with Carson’s story. When I think about the hours we have spent wrestling with the words of an author we share a love for, I think about the concept of friendship as active collaboration.

In the exhibition Tom has curated, I see negative space. Absences are necessary for perception. The mundanity of empty floor space that allows you to move around Dayle Palfreyman’s sculpture Stoma without disturbing its teeth; the light projected through empty air that gives existence to Willa Smart’s video work trying to tell you something I can’t. I worry about the space between myself and the people I love. Reflecting on Carson’s exploration of eros, I try to conceive of distance as necessary for love, and for creating. I remind myself that eros relates to Socrates’ understanding of wisdom as something alive. Carson writes that wisdom is “a living breathing word that happens between two people when they talk. Change is essential to it, not because wisdom changes but because people do, and must."3 Certainly even necessary change creates displacement of the self. The baby teeth fall out, and will never fit back in, despite being completely a part of you.

Steph Arrowsmith, Pulled From The Bed and Shadow For Company, both 2022, oil on wood. Dayle Palfreyman, Stoma, 2022, steel, silver cast teeth. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Another writer concerned with necessary distance, Professor of Philosophy B. Keith Putt, approaches the idea of prayer as a conspiracy between two creative individuals—the person praying and God. Putt connects embodied prayer to breathing, similar to Carson’s description of wisdom as “a living breathing word.” 4 He says that in breathing we inhale the Spirit’s prayer so that we might exhale it again as an offering to God in a divine/human conspiracy (from the Latin con “together”, and spirare “to breathe”) so our every breath participates in intimate yet intangible relationships.5 Carson writes that eros is in between. Without distance perception and desire cease to exist. The pleasure of distance is that it creates previously unforeseen angles of vision. We take delight in what surprises us, in the act of revealing, which depends on gaps (openings of time; breathing space) to be at all effective.

Awareness of the intimacy of distance brings some comfort when I contemplate that the clever and beloved friend of mine who curated this show will soon be overseas. In Eros the Bittersweet Carson writes about a fictional city whose inhabitants do not experience desire, saying “They bury their dead and forget where [...] A city without desire is, in sum, a city of no imagination.”6 If desire is what motivates the mind to imagine, and remembrance of that which is not present is the precursor to imagination, then all creative acts are undertaken in a state of imaginative longing. Desire cannot transcend imagination. The works in On Blushing portray desire existing in the boundaries between you and me, being and becoming, as well as desire to collapse those boundaries at the cost of eliminating eros from the relationship altogether.

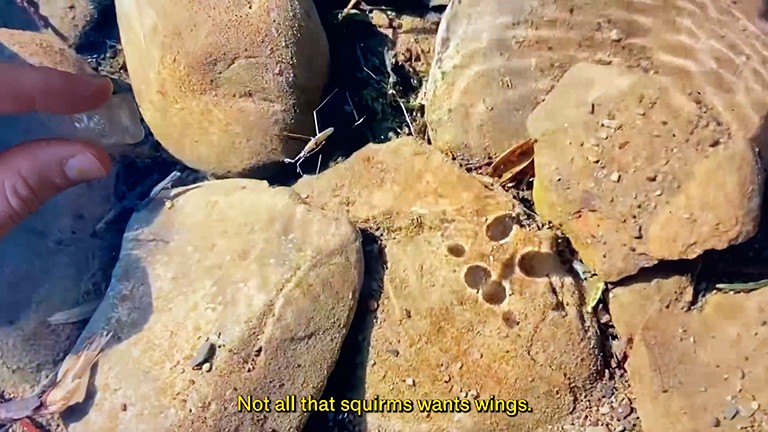

In all honesty I feel I have a lack of authority to approach the subject of eros in writing. My personal work (both my private writing and the ceramics I create) has always been concerned with and informed by relationships, but friendship rather than erotic desire has been my primary realm of exploration. I wonder if this is why I found great comfort in Willa Smart’s video and text works, balancing on rocks and light. These works seem to be interested in the quieter aspects of desire, rather than the drama that erotic moments often evoke. Here we find eros in the everyday, in the unexpected. Bodies of water carrying life cycles under our noses, the language of stones that you must pay attention to in order to learn from. Places that do not perform eros for you, but that may reveal aspects of unexamined desire that no dramatic relationship could. In her essay On Fasciated Fantasy Willa writes that “what I want is what I won’t see coming” .7 The unreliability or unpredictability of eros in human relationships is left by the roadside as the artist looks to meadows and rivers instead, seeking exploration rather than conclusion. In these pieces the non-human other (water-strider insects, a collection of stones) takes precedence, drawing attention to a depth of desire beyond the typical understanding of eros, one arising instead from non-human landscapes.

Willa Smart, trying to tell you something i can’t, 2022, single channel digital video, still.

Dayle Palfreyman’s work Stoma takes its name from the word for any opening into the body (either naturally occurring or medically created). The sculpture consists of small hand sculpted steel rods standing straight up from the concrete floor, balancing casts of the artist’s baby teeth on their tips. Circling this piece you may notice how the rods are arranged in the idea of an oval, suggesting the shape of a vulva, the opening of a uterine stoma. The linking of the mouth stoma and the uterine stoma—creating a labia like shape with deciduous teeth—collapses the body into a fantasy of symmetry. As above, so below. Giulia Sissa talks about how the polarity of subject/object in a relationship of desire creates absurd effects; both ethical and erotic.8 When experiencing desire one’s logic often becomes the logic of dreams. Fantasy confuses boundaries that science or order attend to. Elsewhere Carson notes that in myth, women’s boundaries become pliable.9 Heroines are distorted, transformed, mutated, penetrated. Greek myths invoke the imagery of apples when describing desirable women, conflating bodies with food, creating the somewhat absurd language of desire as appetite.

Dayle Palfreyman, Stoma, 2022, steel, silver cast teeth (detail). Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

-when ice gleams in the open air,

children grab.

Ice-crystal in the hands is

at first a pleasure quite novel.

But there comes a point—

you can’t put the melting mass down,

you can’t keep holding it.

Desire is like that.

Pulling the lover to act and not to act,

again and again, pulling 10

Within this poem the Ancient Greek dramatist Sophokles alludes to the idea that desire is pleasurable, but an acutely painful pleasure like holding ice in your hands. The desire for ice is a pleasure with time constraints. It ends when the ice melts, it grounds you in the present moment. It is also reliant on novelty, and novelties are always short lived. Carson writes that “Novelty is an affair of the mind and emotions, but melting is a physical fact.”11 Steph Arrowsmith’s oil painting Ice In Twilight reminds me of eros’ connection to the imagery and language of melting (a fragment of a description of experiencing desire from the poet Pindar goes “...like wax as the heat bites in”12 ). Taking inspiration from a subtly beautiful piece of mise en scene from the first Twilight film, the painting luminously delivers the image of two ice dolphins overlapping, dripping. With only one drip falling from the bodies, it seems the melting of the two dolphins has only just begun. Desire asks you to relish in the sensation of melting, in your own bittersweet way. To save the ice, you must freeze your desire to hold it. In holding on, you risk forgoing the satiation of eros altogether.

Steph Arrowsmith, Ice in Twilight, 2022, oil on linen. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Alice Langbrown, Locket 2, 2022, bronze, composite silicon and pigment. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Alice Langbrown’s bronze sculpture series Lockets bring my heart back to one word this show is curated around: bittersweet. The sharp, warped frames Alice has created dangle silicone biomorphic plums, gripped by bronze teeth. These frames are fantastic relics of desire. The process of experiencing Eros is bittersweet, “Homer and Sappho concur…in presenting the divinity of desire as an ambivalent being, at once friend and enemy, who informs the erotic experience with emotional paradox."13 The human impulse to retain a part of love in a locket, or a poem, or a photograph, always falls short. Yet we keep trying. We take beauty out of context and our attempts to preserve it in resin succeed only in distorting it further. The Locket series is heart wrenching because the artist has accepted Eros/eros ‘as an ambivalent being’ in order to create fascinating, beautiful pieces. The divinity of desire, the bittersweetness of eros, comes from mystery. The charge of eros alerts a person to the boundaries of themselves, to the mysterious distances, the powerful strangeness between self and others. As Carson says, “Who is the real subject of most love poems? Not the beloved. It is that hole.” 14

---

Beth Harris is currently studying a BFA at Massey University. Her interests lie in ceramics, theology, cars and friendship as collaboration.

-

1.

Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

-

2.

Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red, (New York: Vintage Contemporaries, 1998).

-

3.

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet,176.

-

4.

Ibid.

-

5.

B. Keith Putt, “Too Deep for Words: The Conspiracy of a Divine Soliloquy,” in The Phenomenology of Prayer, ed. Bruce Ellis Benson and Norman Wirzba (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005).

-

6.

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, 217.

-

7.

Willa Smart, “On Fasciated Fantasy”, Open Space, March 29, 2021. https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2021/03/on-fasciated-fantasy/

-

8.

Giulia Sissa, “Anesthetic Humanism? Conflicting Ethics of Pleasure and Pain”, lecture recorded for Posthuman Antiquities: A Cross-Disciplinary Conference at New York University, November 14-15, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqTJIN3ywyQ

-

9.

Anne Carson, Men In the Off Hours, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000).

-

10.

Sophokles, The Lovers of Achilles, as translated and quoted by Carson in Eros the Bittersweet, 211.

-

11.

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, 154.

-

12.

Pindar frag. 123.10 -12 Snell-Maehler, quoted by Carson in Eros the Bittersweet, 34.

-

13.

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, 4.

-

14.

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, 52.