Exhibition Essays

Rupture / capture

March 2016

The end to that eye

Marcus Moore

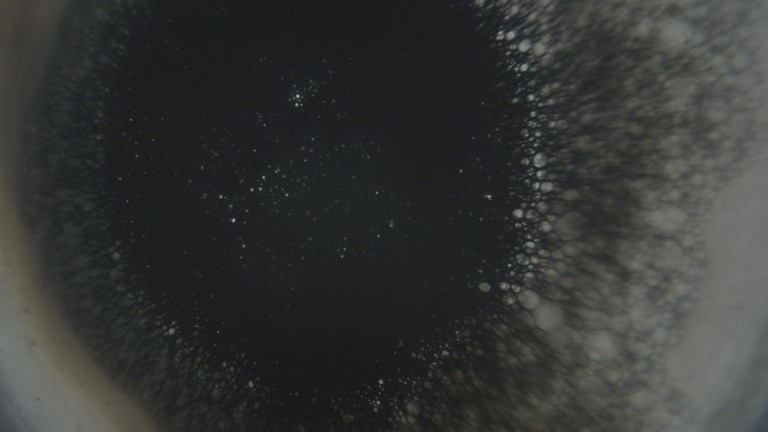

Johanna Mechen, Rupture/capture, 2016, video still.

[T]here is something essentially self-destructive about the human theoretical eye: our very openness to the world—the very relation that is our life—is precisely what seduces us into forgetting that before there is an eye that acts as a camera or window there must have been something like an orientation or distance, a relation without relation.

Claire Colebrook, ‘Framing the End of the Species: Images Without Bodies’1

From the beginning this response to Johanna Mechen’s Rupture/capture was to say something on the post-human eye, the eye becoming un-fixed from its biological and its anthropomorphic being/existence. The post-human presents a way of taking-on the organic as persisting in a time of heightened technological attachment—as well as a moment of heightened intercourse of the visual. What exactly is the eye’s existence? First it is to provide some context for the project and consider the complicity of the looking eye for a screen-based document.

Perhaps it is best explained that Mechen’s project divulges in some type of liaison between optometry and photography undertaken by the artist together with optometrists, eye specialists and members of the public as the 2015-16 Enjoy Summer Artist in Residence. It is very well researched in terms of the technical apparatus and equipment used in both fields, and the sensory effects of these upon the eye. The project then discloses what can be gained through an explorative inquiry of these different disciplines; both epistemological and metaphorical, at once truthfully represented and made un-true. It is a pared back use of the gallery space. Two photographs are hung on the left wall titled Model and Meter and a short film is projected on the rear wall.

![Johanna Mechen, Model [left], Meter [right], 2016.](/media/cache/ec/e0/ece039f5c3763fe14094d4333b509b7c.png)

Johanna Mechen, Model [left], Meter [right], 2016.

I turn my attention to Meter, the photographed vertometer on the wall.2 It reminds me of the objects we use to better understand the workings of human bodies and improve their deficiencies. It suggests the bind humans have to our direct dependency on technology to be and live. Without it we would not come to know, and yet, in the limits of my interpretations it formally highlighted the inherent complexities and dissimilarities to inquire into the manner the eye is to be known and perceived. Ahead, an audio-visual document is projected onto the back wall. There is a seat, a bit like a pew, offered to sit and watch.

The opening of the document is equivocal: a transition from the surface of the moon, or it could be the surface of a cornea under microscopic vision, to white-like-light circle. It lays the foundation for the document; assuming that if there is a subject looking outward from the eye, then there is another looking into the eye. Mechen’s proposition is, essentially, to take a viewing device and turn it inward into the eye, as an instrumentation of examining that same eye. The resulting work is epistemologically factual—the tool to better know the individual’s eye and what it outwardly may see and observe—as it is also the creation of glorious portals to strange and abstract mutations.

The matter itself of watching an eye on screen is crucial. In Visual and Other Pleasures Laura Mulvey highlights three principal looks: the look of the camera; the look of the audience watching the film; and the look of the characters on screen.3 Mulvey exposes underpinning cultural codes concerning the behaviours of looking and much has been extended from it. Perhaps less widely known is the work of Kaja Silverman. In the Subject of Semiotics Silverman employed the term suture to explain the complex role of the camera in narrative subjectivity. Suture is concerned with how the camera assumes a necessary role in the establishment of character and narrative in film—at the mise-en-scène it provides a unique standpoint in relation to characters from which a psychological disposition is attenuated or empathy enhanced—but it is not without its bias. She writes, "This sleight-of-hand involves attributing to a character within the fiction qualities which in fact belong to the machinery of enunciation: the ability to generate narrative, the omnipotence and coercive gaze, the castrating authority of the law”.4 While there is no dramatic set of character personae in the work, Mechens’s Rupture/capture is not without a critique of the phallocentric controls of photographic disciplines and ways in which the woman as gendered subject is viewed as pleasurable, constructed for the dominance of the male gaze historically and culturally: holding in Mulvey’s terms a ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’.

When watching certain frames from Mechen’s work, effect sequences suggest intrusion(s) into the pupil of the eye; subsequently making apparent the inherent bind a relationship the eye has to the screen and the spectacle of watching ‘film’, but not without complications. Some of this causation was part of the voice-over narration. Conditioning the biological eye with the technological, the spoken voices of two females, perhaps optometrists, are unseen and somewhat detached, mechanical in their persuasion—“sharper now or now; sharper now or now; sharper now or now”. That they are unseen is one thing. With no ability to gain explicit use from their prompts about my vision—it was in my reading to learn about the deficiencies of my own eye in other terms—the disembodied medical voice directed where to gaze and on occasions pronounced how to use my eye upon the screen. Fitting. In Silverman’s terms—from the late 1980s but more than useful—it might be likened to an acoustic mirror (1988); sound/voice as a ‘fantasmatic projection’, authorship pronouncing difference at any belief in a universal human ‘we’.5

And to probe or enter the eye procures certain vulnerability. In making the eye the subject of her study, using it as both subject matter and conditioning agent, does Mechen’s work render visual the glimpse into understanding being as different from anthropocentric norms? If posthumanism has emerged as a relatively broad spectrum of concerns, theories and philosophies attendant upon a certain shift in the relative ways we might ‘best’ comprehend the human subject, it is to grapple with how ideas of being human now extend well beyond qualitative norms of what it is to be human.

So now I want to say something about the vitreous eye floaters—these things that around halfway through the film float into it as a subject. I write to mine as discovered by Marcus Moore when I was six years old.

I sunbathed a lot on the patio of our family home. My body would absorb the warmth from the heat of the sun that had been trapped in the fired bricks that I lay upon. When closing my eyes I would follow the incredulous shapes across my field of vision. They would cross my organic screen from left to right, then leave, then reappear at left. Following their trace kept me for more than an hour on end. I went somewhere with them and when I returned I dived into a Para pool and then would go back and lie down on the patio and ask my body to return them to my eye. I have written my encounter just now with my body years ago, collapsing it all far too neatly. But the thing about vitreous floaters is they move within a fluid membrane, a territory of the body, maybe they can cross time and space. I’d like to imagine so.

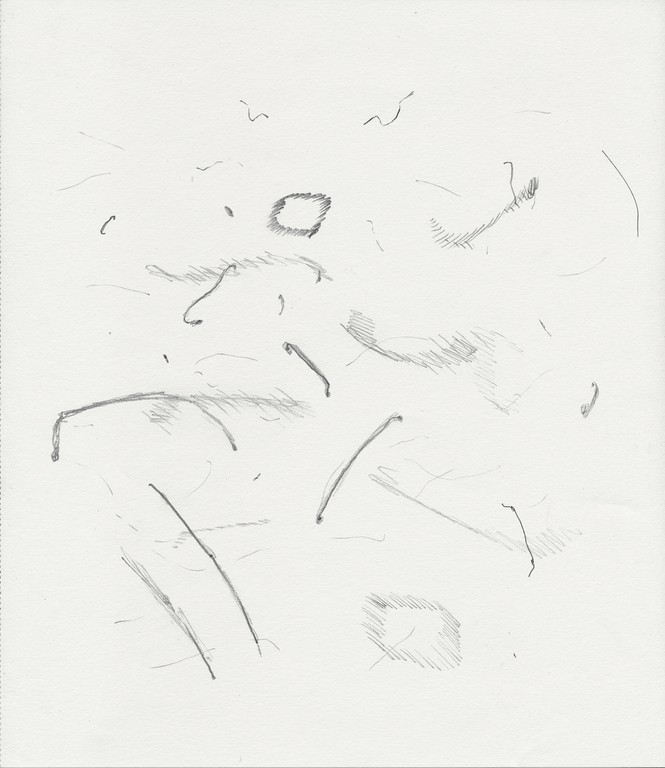

Mechen invited and asked participants to discover then draw their own at Enjoy over one weekend in the late 2015-16 Summer. To make these floaters apparent, Mechen lends to others another medium completely. Drawing and a fish bowl. This is what she says to describe the idea and process:

The eye floater drawings were the result of a two-day event that I ran at the gallery. I invited people (general public, optometrists…and the art world, through those channels) to come and look for their floaters against the white wall and draw them (drawing paper, HB pencils…). I talked to people about their experiences and feelings about these obstructions to sight—or their awareness of floaters, general information sharing about eye conditions. People often talked for a long time. I had 26 or so people draw and play with a fish bowl of water and dust on an OHP … I told them I would bind the drawings into a book or include them in the film work…. So yes, they are filmed (sat on the end of a cable coil which was slowing unraveled by me while my daughter filmed, saying, ‘slower mum, now faster, slower, slower'…).6

Floater drawing No. 4, 2016.

In the manner of its production there is an interstitial passage from the corporeal body to a spectral semblance. From fluid biological territory to fluid technical territory they dance across the personal eye and then project upon a screen. The projection does not of course harbour anywhere near the same sensation as mine upon the patio, but it is an innovative process and representation of the phenomena. Each of the drawings is unique. It is then a seven-year-old kid who tells the photographer about duration. In that there is something marked about the process. A floating in the eye, by the shutter of the eyelid drawn—then the shutter of the camera catches them. It is not the camera, nor the photographer, but the mediated experiences produced across (fluid) boundaries that become the matter in the post-human turn.

Here, a theory of the subjective might emerge as Rosi Braidotti suggests “an empirical project that aims at experimenting with what contemporary, bio-technologically mediated bodies are capable of doing”.7 From this perspective I would argue that Mechen’s project with its use of the science and technologies of optometry shows visually the opportunity for new boundaries from the known body into otherness to be made through observation, drawing, then technologically produced ways of recording and seeing. I accept, however, it is a creative output in moving image that represents and draws attention to themes and issue, less Braidotti’s tenet of the actual living mediated body. But as such a link to Deleuze’s notion of becoming other may also be considered.

Attendant on the technology used to understand the eye and the technology used to film, Rupture/capture becomes durational within which the viewer’s subjectivity as watching eyes with their own is being constantly conditioned and questioned. While watching the film I had made a note to re-read a passage where Deleuze famously writes to “open us up to the inhuman and the superhuman durations (durations which are inferior or superior to our own), to go beyond the human condition”.8 For Deleuze, that is what philosophy is, a becoming other is a way to comprehend of any territory as being in constant change, constantly coming into existence rather than possessing a fixed unity. He cites the cinematic assemblage as an example: things disappear and are replaced of images in time—such that it conditions human subjectivity in new terms, or in fact transcends what we can know of it.

Claire Colebrook—the author I quoted at the outset of this response—writes, “it is the cutting power of the eye that needs to be thought: the eye would be approached as a form of synthesizer, but as an analog rather than digital synthesizer.”9 For Colebrook this thinking means “the eye does not need to free itself from imposed distinctions to return to the flow of life, but should pursue ever finer cuts and distinctions, beyond its organic thresholds”.10 At its best—much less privileging a relationship sought between photography and optometry—Mechen’s work could be seen to begin to enter this important philosophical ground. Underpinning it is a set of ideas to attempt to re-acquaint ourselves with a new knowing of the world. Again, I am influenced by the writing of Braidotti, who as a feminist philosopher demands a vital materialism for a “new love of the world”.11

But for all its visual-ness, therein, that is a quandary of Rupture/capture, as all the work rests so much on the sensory as visual, and visualized. The eye is such a fucking visual thing.

-

1.

Claire Colebrook, “Introduction: Framing the End of the Species: Images Without Bodies,” The Death of the PostHuman: Essays on Extinction, Volume One (2014) accessed May 15, 2016, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/o/ohp/12329362.0001.001/1:2/--death-of-the-posthuman-essays-on-extinction-volume-one?rgn=div1;view=fulltext.

-

2.

Paired with Meter is Model, a glass bulbous form that at first appears to reflect the surrounding world on its convex surface. Far from being the immediate surrounds, the reflection carries the past—Mechen has mapped upon it imagery in reference to the history of Enjoy’s current location, occupied by the Berry & Co Photography Studios from 1897-1931. The gap between what is factual and what has been constructed is teased.

Te Papa Blog “A slice of Wellington life: the Berry & Co collection,” accessed May 3, 2016, http://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2012/10/25/18566/.

-

3.

Laura Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1989), 25.

-

4.

Kaja Silverman, The Subject of Semiotics (New York: Oxford UP, 1983), 232.

-

5.

Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror (1988; repr., Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2008).

-

6.

Johanna Mechen, email correspondence to the author, 14 April 2016.

-

7.

Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 61.

-

8.

Deleuze, Bergsonism (New York: Zone Books, 1988), 28.

-

9.

Colebrook, The Death of the PostHuman.

-

10.

Colebrook, The Death of the PostHuman.

-

11.

In addition to the book The PostHuman., readers may well be interested in the 2014 interview ‘Borrowed Energy’ published in Freize here, http://www.frieze.com/article/borrowed-energy;

and one of Braidotti’s recent keynote addresses can also be found here, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3S3CulNbQ1M.