Exhibition Essays

Shelter or Marquee

April 2007

An essay about several published versions of a column republished as a review within this essay

Mark Amery

-1-

Enjoy is producing a PDF catalogue of its 2007 exhibition programme in 2009. This poses interesting questions for me as to how we re-engage with artwork over time — particularly when the artwork itself features a reconstruction of something remembered: in her installation at Enjoy, Louise Menzies reconstructed from memory a work made by Ryan Chadfield during art school.

I was being asked to revisit as essay, a review I wrote about Menzies’ exhibition within a newspaper column in 2007. This left me with questions about how I could honestly reconstruct Menzies’ work from memory. Also, given that Menzies’ exhibition was for me concerned with the constructions that are placed around speech, it also made me consider how differently written work reads depending on its context and the editorial framework which is built around it.

It happened like this.

On Friday 27 April, 2007 the Dominion Post published 821 words attributed to myself as author which included, amongst other items, critical consideration of Louise Menzies’ exhibition Shelter or Marquee at Enjoy Gallery.

The newspaper’s subeditor gave the piece the title Does size matter any more?, and selected the following pull-quote to draw or ‘pull’ attention to the article: “As a whole the work questions whether such words as spelt out here, once so politically powerful, have been emptied of their import.”

The article was illustrated by a reproduction of a different work from the exhibition (Wetherfieber (after Ryan Chadfield)) from that referred to by the author in the pull-quote.

Then on Monday 30 April, 2007, the website thebigidea.co.nz — using the same title but with no pull-quote — published 849 words, proporting to be the same text. The same artwork was used to illustrate the text, but only the left half of the image was reproduced.

This however, came directly from the author, rather than from the Dominion Post, and was thus not subject to the same subediting. Aside from different paragraph returns — strongly affecting the way any article is read — and a few other minor changes, two passages may be found in The Big Idea version that were left out of the Dominion Post version.

Firstly, the second part of the following sentence: “The gallery (Enjoy) is as much an office, a small research library and gathering place for a community: for this point in time a shelter for artists, a marquee for a party.” And secondly, a comment in its entirety about the carpeted steps in the above photograph: “To be a mechanism by which we get to, as the artist says “give air (or shelter) to individual narratives about the world”.

On request to the author the article was then reprinted on Enjoy’s website with no illustration or subtitle. It has not been analysed as to whether further editing changes were made to the text at this point, nor which version Enjoy’s was based on: my original, the Dominion Post’s or The Big Idea’s.

Two years later, on 14 May, 2009, Enjoy commissioned this essay from the author, to be between 1000 and 1500 words. Wrote Jeremy Booth of Enjoy in an email, “It’s come to my attention that an essay on Menzies’ exhibition was never written, and that your review has been serving the purpose of supporting written material until now. This is great, but isn’t quite appropriate for our PDF catalogue.”

The essay which you’re now reading features the following 451 word excerpt from the original review, followed by the author’s thoughts two years on.

“(Enjoy’s) current exhibition by Louise Menzies is entitled ‘Shelter or Marquee’, and

that title expresses something of the gallery’s function. It’s increasingly no inconvenience that one of its four walls is windows. It allows Enjoy to look out on the world and the world in return to look in. The gallery is as much an office, a small research library and gathering place for a community: for this point in time a shelter for artists, a marquee for a party. When I turned up on Monday part of the installation had been put to one side to allow for a musical performance as part of the exhibition.1 A beer keg and a beer crate of records featured.Meanwhile Menzies’ exhibition had been keeping my mind piqued with the possibilities

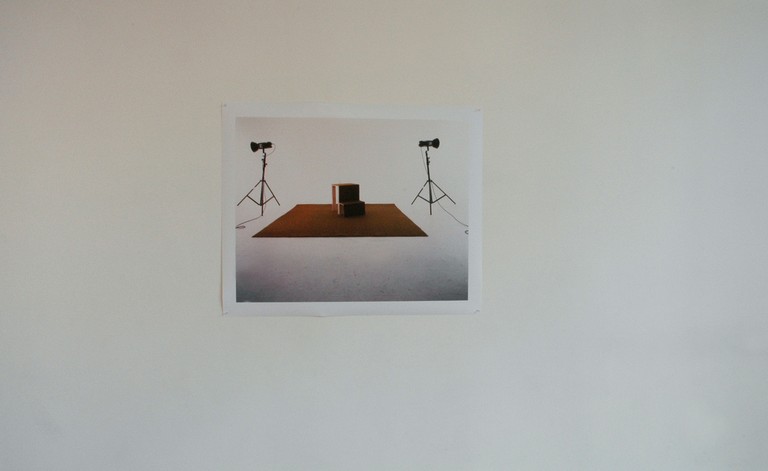

it suggested since I’d seen it the week before — a true sign of a strong show. Menzies’ work suggests that the small can broadcast loud. In a central photograph a piece of carpet and some carpeted steps in a studio for a photograph’s subject to pose on are empty, and the lights for the photo shoot point outwards like speakers. It’s as if Menzies is expressing a wish to shed light on the real world beyond photography’s stagings.Captured off kilter in a sea of studio white, the lights are animated (they seem off-balance, as if they’ve started walking), and the carpet is rippling; the whole scene seemingly engi- neered to knock you off your guard and make you ask questions. The steps for me resembled a makeshift vacant soap box, as if welcoming you the viewer to step up and make your own statement. To be a mechanism by which we get to, as the artist says “give air (or shelter) to individual narratives about the world”. The work itself is in fact a recreation from memory of one made by art school colleague Ryan Chadfield — all this together with the musical performances raises issues of individual ownership and collective creativity.

The soap box analogy fits with the second component of the installation, a cloth banner in pink with yellow tassels with the words ‘Labour & Free Will/Love & Revolution’ on it. The banner (which has a romance reminiscent of something carried by a brass band say) is mounted on a cheap wooden billboard, like a roadside election hoarding. As a whole the work questions whether such words as spelt out here, once so politically powerful, have been emptied of their import. It questions whether the power of language has been muted, and what in their work out in the world contemporary artists now have to say politically. McCahon told us that he needed words; Menzies questions whether they’ve now become spent.”

-2-

The framing and collaboration involved in the public expression of words, and the way communication is dressed up in order to gain attention, were things that piqued my interest in this work of Louise Menzies. This wasn’t what the exhibition blurb suggested the work was about, but then feeling the need to clutch onto such blurbs while considering an exhibition suggests the art isn’t providing the openings itself.

Like Enjoy’s large window, the artwork looked out for me, shedding light on the context and means for making speech and art public. This was made manifest immediately with this exhibition as you came in the door: the first thing you faced was the back of a hoarding carrying a text (of a size and material most familiar from street corners during election campaigning).

Shelter or Marquee opens out clearly and powerfully how important the furniture of communication is: do you use a microphone, a megaphone or a brass band? Powerpoint, pedestal or paper? We trust the written word, we value its concreteness but we don’t question enough how much the world shifts around it and profoundly affects the way it sounds or it is read.

The example in section one of this essay of editorial changes is relatively minor. It is rare now for my work to carry a title that I came up with, and it will generally be provided with a subtitle I did not create. Art critics like myself have been known to have their texts cut in half without any consultation, altering in the extreme a carefully balanced work of criticism.

Back in 2007 I was blessed with a newspaper subeditor who ‘sheltered’ me from brutal unsympathetic cutting, but wasn’t afraid to make incisive changes where I had over-indulged, as he did above. The production of such texts is in this way collaborative, but that collaboration is generally hidden. In this way the text starts to become removed from the experience of the art — about as close to it as the badly printed reproductions that accompany them. No matter how much time elapses, any review is a recon- struction, affected by the experiences you have after you leave the exhibition room.

I can’t go back two years and re-experience the work. I can’t, knowing I’m writing an essay in two years time, attend the opening night and performances that I missed last time round. I can’t interview the artist as they and their practice were back then.

On June 2, 2009 Louise Menzies emailed, writing: “Please just let me know if you have any questions”. What could I ask to which the answer wouldn’t distort my memory of the work? Did Ryan Chadfield send Menzies a similar email when she went about reconstructing his work?

Ultimately Menzies’ Shelter or Marquee proved memorable because I found it good art. It left me reconsidering the way speech is propped and dressed up long after my words were originally published.

-

1.

In the final week of Shelter or Marquee, Menzies invited Kristen Wineera and Stefanimal to perform solo musical sets in the gallery space, as part of the exhibition. The space, and the elements of the exhibition were re-configured around these performances; introducing a dynamic of individuality in contrast to the implicit ideas of collectivity invoked by Shelter or Marquee.