Exhibition Essays

Was that cannon fire or is it my heart pounding?

August 2012

Ship of Artifice: Decoding Reality in Was that cannon fire or is it my heart pounding?

Morgan Ashworth

The 1942 film Casablanca gave us “Of all the gin joints in all the towns

in all the world...” and “Play it [again], Sam”. And not long after Rick Blaine toasts Ilsa with “Here’s looking at you, kid”, she asks him “Was that cannon fire, or is it my heart pounding?” Just as Ilsa’s question captures two starkly different concerns, the title also tells of an exhibition concerned with discerning meaning. The selected works in this show play with how film can either aid or interfere with this.

A lenticular photograph in Nathan Pohio’s Phantom Sea Rider shows a colonial sailing ship, captured in a black-and-white moment of motion on the waves.1 We cannot hold the image in our hands and tilt it back and forth to access the movement it captures, instead this is mediated through Pohio’s camera. Film is by all accounts considered a more advanced method of recording reality than the novel lenticular photograph. Here, however, Pohio’s manipulation confuses and distorts reality. The viewpoint traces unpredictably across the surface of the image, framing small areas at a time and moving back and forth between the image’s two stages. Attention is drawn to the limitations of the medium; to its inability to tell any more than a split-second of its subject’s story.

Phantom Sea Rider follows an earlier video work, Landfall of a Spectre, 2007, which describes the same image of a ship. The artist describes this work as ‘an excursion into a description of movement’.2 Both works probe the narrativity inherent in the film medium, tied as it is to forward movement through time and space. The two moments in the ship’s narrative appear and reappear, redirecting and looping time, changing a captured split-second into a garbled, non-linear cycle. The circularity of Phantom Sea Rider brings to mind American artist Jessie Henson’s 2009 installation Armada, for which she collected generic maritime paintings and hung them edge-to-edge so they perfectly encircled the exhibition space. The collaged horizon lines align to create the sense that all the ships occupied the same ocean, racing or keeling haphazardly in all directions. Henson’s constructed narrative, like Pohio’s, is devoid of any clear forward momentum or starting point. Both works return the viewer to where they began, before sending them off again. The worlds they construct are self-contained, limited; deliberately meaningless.

Henson and Pohio remediate the universal imagery of the majestic sailing ship, but where Henson’s many ships suggest a multiplicity of readings, Pohio’s is unavoidably much more meaningful. Although Nathan Pohio resists telling an explicit story with Phantom Sea Rider, there are always stories to be told, and the artist’s Maori heritage informs this. The erratic movement of the camera in Phantom Sea Rider obscures the ship initially, delaying the delaying the viewer’s conventional semiotic response. Upon examination, the ship depicted is a large vessel with many sails, recognisable due to its resemblance to the HMS Endeavour, which is impressed on the New Zealand 50 cent coin. Designating Pohio’s ship as the Endeavour, which bore Captain James Cook to New Zealand in 1769 and signalled the beginning of European colonisation of the country, would be trite and elementary. But some of Pohio’s ancestors had significant roles in fostering relationships between settlers and local Maori, and he acknowledges his tipuna Horomona Pohio’s role as informing his approach to his art.3

Ships densely populate the stormy seas of New Zealand’s history, for both the Maori and later arrivals. Pohio has told of his own maritime ancestry, explaining that ‘my ancestors were exporting flax to Australia. They owned ships and were making a real success of it. The Crown said, no, you people can’t run a successful business, you’re natives, and it got stomped on, shut down.’4 His black and white ship, frozen in a moment of time, becomes a flickering memory, a visualised fragment of his family’s story. The narrative becomes cut off, abruptly, by Pakeha authorities policing the resources they introduced to the Maori. Or is the ship a symbol of the Maori sailing out of reach of their colonisers’ grasp? The avoidance of a concrete point of view in Pohio’s film piece suggests that every story is equally possible. A politicised reading can stand alongside the romance of a pirate ship, a ghost ship, an explorer hunting for Atlantis.

Consider the two captured moments of the ship not as two snapshots a second apart, but as two completely different moments. Maybe the first is the ship on its maiden voyage, the second moments before the mast is snapped on its final sail. Maybe the ship is not a watertight vessel at all, but a tiny model snapped at close range. The illusion of the lenticular photograph extends beyond simulated movement, speaking to the illusions fundamental to cinema itself. A pirate ship can be two feet tall and rolling hills are inside sound stages. Truman Burbank boards the Santa Maria and sails until he reaches the edge of the world, his sailboat’s prow crunching through the painted sky.

Ronnie Van Hout’s 1997 Space Suit hangs on the wall along from Pohio’s monitor, making no apologies for the barely-illusory nature of B-grade cinema. The gaudy silver lamé suit lifelessly sags from its wire hanger, but one imagines that stretched around an adult figure it would do little better at convincing anyone it is a functional space suit. It becomes comedic, a kitschy, shiny garment without any of the trappings of a pop-culture spaceman: fishbowl helmet, padded gloves or moon boots. Space Suit draws attentions to the act of acting; putting on a costume and assuming a role, whether convincing or otherwise.

Van Hout’s solo show, I’ve Seen Things, installed at the Dowse at the same time as Was that cannon fire..., addressed related questions of self in cinema. His re-enactment of a scene from Blade Runner, where the artist plays both characters, is another unashamedly low-budget riposte to the questions of identity and memory running through Philip K. Dick’s book. The human and replicant characters are both Ronnie Van Hout; they are therefore both human. Androids do dream of electric sheep. Space Suit asks who dreams of electric sheep after the costume comes off and the actor goes home.

Another of Ridley Scott’s Hollywood dramas appears in Mexican artist Artemio’s humorous interference with the 2000 film Gladiator. Artemio’s 2004 work, in collaboration with Raul Luna, demonstrates the result of a painstaking effort to remove every character in the film except for Russell Crowe’s Maximus. The scene is set with an empty camp, tents billowing and eerie chants heard from absent observers. Maximus primes himself to fight, to ‘give them something they have never seen before’. But there is no one there. He grapples with no one but himself, his tunic splattered with the blood of an invisible opponent. Crowe’s legendary line, ‘Are you not entertained?’ is delivered to vacant stands, and instead of being a hero, Maximus is revealed to be a deranged, disturbed, and violent man, fighting internal demons of conflict and masculinity.

One sees how constructed the violence found in successful Hollywood cinema really is, and how damaging that can be when reflected back upon the individual. The artifice of this machismo is compounded when one considers the performance of Hollywood ‘tough guy’ Oliver Reed in Gladiator. The actor passed away unexpectedly before filming was complete, and his role was completed with complex post-production visual effects costing approximately $3.2 million, where Reed’s face was mapped to the actions of a body double.5 Even the tortured actor is no longer required.

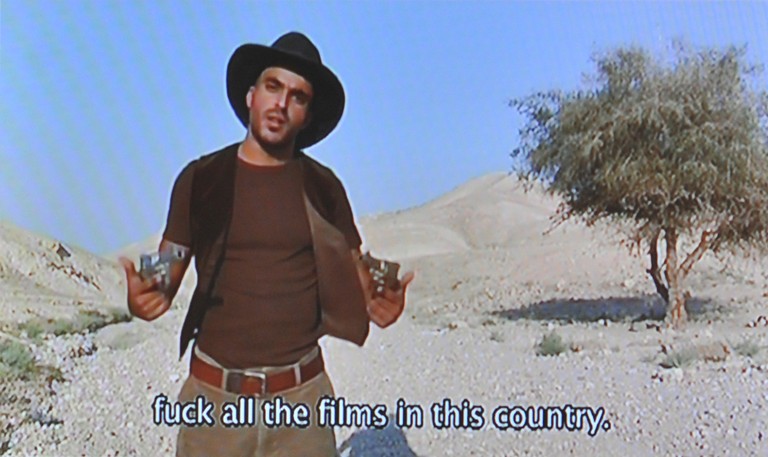

The ‘shooter’ in Ihad Jadallah’s The Shooter is just as much the cameraperson as the man with the gun. The Palestinian filmmaker challenges the turbulent and violent environment seen in international news reportage of his home; representative of a conflict which is undeniably in existence, media depictions nonetheless distort and dramatise this conflict until it suits the formula to which Western viewers are so accustomed. A young man faces the camera candidly, breaking the fourth wall and disparaging the John Wayne hero figure that appears in the conventional cowboy movie. His pistols are plastic; his desert is in the Middle East, not the West. Soon we see repeated attempts to film an international news report, the camera following a gunman through a building damaged by war until he passes the young female reporter. The scene is recorded over and over again until it is exposed as the farce that it is. Film and its conventions obscure the reality of the conflict in Palestine, forcing it instead inside a foreign frame. The Shooter sees a Palestinian artist reclaim and subvert the medium, appropriating its techniques to reveal its shortcomings.

Ihad Jadallah tells the story that is outside of the camera’s frame. Ronnie Van Hout tells the story that is off the stage. Artemio tells the story that is inside the actor’s head. Nathan Pohio tells the story of a thousand stories. But Mike Heynes tells a story outside of our field of vision completely. His 2012 film Falling was easy to miss in Was that cannon fire..., projected as it was on the angled ceiling of the Enjoy space. For the majority of the time the work shows a simple cloudscape, simulating a skylight within the white frame that most likely did contain a skylight at some point in the building’s history. Occasionally, however, one will catch the tumbling body of a suited man as he falls past the “window”. Heynes uses humour more openly than the other artists. His falling man is the comic hero of a silent film that no one is watching.

The thinking running through this exhibition brings to mind the Ship of Theseus. The Greek philosopher Plutarch asked if, as the ship decays and all its parts are replaced plank by plank, is it the same ship, or a new ship? If Nathan Pohio’s Phantom Sea Rider showed a different ship, would it matter? What lies in the space between cannon fire, and your heart pounding?

-

1.

A lenticular image combines multiple still photographs to create the illusion of depth or motion. A technological precursor to cinema, as the viewer moves from one viewing point to another, the frame appears to contain a briefly moving picture.

-

2.

Correspondence between the artist and Mark Amery shared with Claudia Arozqueta, curator, July 2012.

-

3.

Nathan Pohio in conversation with John Walsh’, Taiwāhio: Conversations with Contemporary Maori Artists, ed. Huhana Smith, Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2002, 120.

-

4.

‘Gladiator (2000 Film)’, Wikipedia.org, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gladiator_%282000_film%29, 2012.

-

5.

‘Nathan Pohio in conversation with John Walsh’, 122.