Exhibition Essays

Strands we Share

November 2024

Strands we Share

Brooke Pou

Kaka-aku is an exhibition featuring Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan (Ngāti Rupe Makea, Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mitiaro, Mangaia), Rosalie Koko (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga, Olosega), Bobby Luke (Ngāti Ruanui, Taranaki) and Vince Ropitini (Taranaki, Ngāruahinerangi, Whakatōhea). Through the forms of kākahu, tīvaevae and moving image, these artists honour the customary ways of their tūpuna while also offering invigorating adaptations that revitalise past traditions. In textile art, innovation is vital. As Lana Lopesi notes in False Divides, “Moana cultures, like all cultures, are in flux, adapting and evolving. It is important to remember that while Moana cultures are firmly rooted in customary practices, they are also active participants in the contemporary world.”1 The artistic practices of tīvaevae and kākahu may seem diametrically opposed, but they both have roots in kaka-aku, literally meaning textile fibre.

Kaka-aku, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

In an essay exploring exhibitions of tīvaevae, Ioana Gordon-Smith explains that “Tīvaevae, often loosely translated as ‘to patch’, is the practice of quilting and embroidery found across East Polynesia. It is commonly thought that missionaries introduced these techniques into the Pacific in the 1800s, first in Hawai’i before they spread…developing island-specific adaptations in each place.”2 The distinctive form of tīvaevaei ta’orei (patchwork quilting) from the Cooks is called “the mother of all tīvaevae” by a member of Tipurepure Au Vaine, the Porirua based Cook Islands sewing group teaching Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan about the art and history of tīvaevae. Each square in Nā Ngapare ngā painapa (Ngapare’s Pineapples) is about 200mm x 200mm of characteristically Cook Island colours. This tīvaevae was first created by Ngapare Poko Taua (1905-1974), Buchanan’s paternal namesake. Ngapare’s determination to create a tīvaevae for her whānau is reflected in each patch, and while it has never been fully completed, it is a revered taonga nevertheless. Buchanan says that learning from Tipurepure Au Vaine these past few months has become “the highlight”3 of her week. These vaine pass down ancestral knowledge and akapapaanga, sending Buchanan on a journey of reclamation. Spending time with the māmās, she has learned to restore her tīvaevae while injecting her own signature flair in the form of golden sequins. Threaded individually throughout her tūpuna’s tīvaevae ta’ōrei, the sequins are a marker of the artist’s hands restoring the work begun by her great-grandmother in a reference to the Japanese art of kintsugi. Instead of colour matching each patch, the artist embraces the beauty in imperfection and heals what was once broken.

Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan & Ngapare Poko Taua, Nā Ngapare ngā painapa (Ngapare’s Pineapples), c. 1905-2024, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Researchers have suggested that tīvaevae replaced tapa in the Cook Islands, asserting that tangata o le moana lives were “previously wrapped in tapa cloth.”4 They determine that both tapa and tīvaevae are valuable textile items and note that the ceremonial uses of tīvaevae today reflect those of tapa pre-colonisation. Tīvaevae are one of the most precious gifts that can be given. They are often the pride of one's household, laboured over for months on end, not just to be used as quilts but also as decorative displays during important occasions such as hair-cutting ceremonies, birthdays, weddings and funerals. Much as Māori wrap our tūpāpaku in whāriki and whatu kākahu, some Cook Islanders choose to be buried with their tīvaevae, meaning older examples of the artform are harder to source outside of museum collections. This exhibition is the first time that Nā Ngapare ngā painapa (Ngapare’s Pineapples) has been publicly displayed—a generous offering to share something so precious in a gallery setting, a place so divorced from its natural habitat.

Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan & Ngapare Poko Taua, Nā Ngapare ngā painapa (Ngapare’s Pineapples), c. 1905-2024, (detail). Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

“Quilts may appear to us as a leftover from an age when people still had time—time to do things that literally soak up time time and make us cherish the product of work as evidence of time well spent”5

Rosalie Koko, Tauhere, Fa’atasi, 2022, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

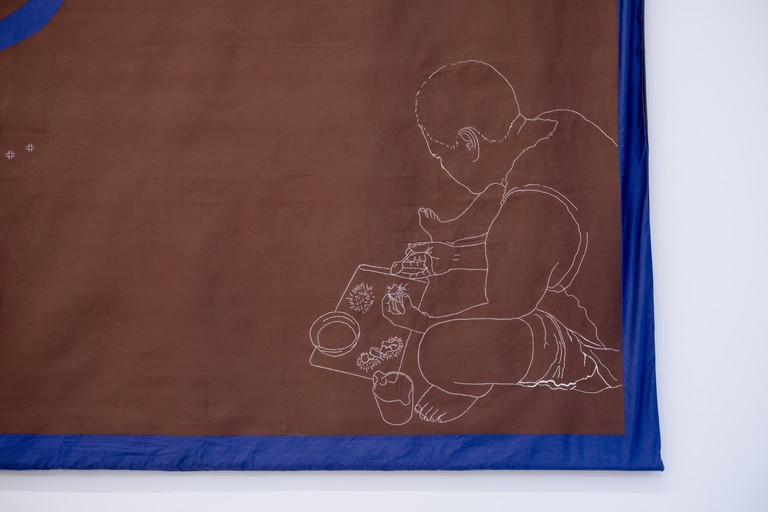

Rosalie Koko has spent time under the tutelage of many kaiako, learning to create a brand new quilt for her Toioho ki Āpiti Māori Visual Arts studies at Massey in 2022. Koko is guided by the whakataukī "O le tele o sulu e maua ai se figota, e mama se avega pe a te amo fa'atasi" / "Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini" / "My strength is not mine alone, but is the strength of many." Referring to the collective practices of tangata whenua and tangata moana alike, Koko acknowledges that the making of this quilt would not have been possible without the many hands of friends and whānau which have contributed to the stitching. Tauhere, Fa’atasi is an expression of converging whakapapa/gafa lines and the applique is inspired by tīvaevae techniques of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. Kōwhaiwhai, siapo and tatau patterns are referenced throughout the work in a paired back colour scheme of brown, blue and white. The artist’s use of muka to embroider is emblematic of the convergence between her cultures.

Rosalie Koko, Tauhere, Fa’atasi, 2022, (detail). Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Koko hand dyed the fabric in this quilt blue in order to represent the moana her tūpuna journeyed across, while the larger brown facet is emblematic of the whenua they landed on. The kōwhaiwhai Koko uses here is called kōwhai ngutukākā—alluding to the recursive pattern and referencing her waka, the Tākitimu, and its shared histories across the moana. For the artist, drawing these shared lines of whakapapa together is a way to honour her ancestry as she learns more about it. There are also figurative portrayals of her whānau members portrayed in the work, their scale and placement perhaps indicative of the times in which they live/d. Positioned at the very top of the quilt is Koko’s great-grandmother, adorned in a tuiga. At the bottom sits her uncle dressed in shorts and a tank top as he eats kina. The outlines of these figures, their actions and garb are familiar to many of us with Māori and Moana whakapapa. Elsewhere in the quilt are siapo and tatau patterns placed between the kōwhaiwhai in what Koko deems a “portal into other parts of my whakapapa.”6 In the making of Tauhere, Fa’atasi, she has chosen to take inspiration from decorative designs seen on siapo and tatau motifs commonly found on the bodies of her whānau in Sāmoa. A core component in the construction of this quilt is the collaboration that went into the making of it through shared mātauranga as well as the practical embroidery and applique.

‘O lima alofa nei sa su’isu’iina lenei ‘ie.

Nā ēnei ringa aroha i tuitui ki tēnei kuira.

These loving hands stitched on this quilt.

Bobby Luke, Oranga Ngākau (2023) & Kākahu Hou (2018), installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

The kākahu that Bobby Luke makes is grounded in his Taranakitanga. Luke grew up at the pā that his whānau are from in Hāwera, spending much of his time with aunties, nannies and his mother, Alison Luke. His strong connection to the land and its history, as well as his matrilineal tūpuna, have influenced his practice as a designer in the form and function of the garments he creates. The pieces from the Oranga Ngākau collection have been made from materials obtained from Parihaka and the artist’s homesteads across Taranaki—they are repurposed fabrics from his whānau, honouring his rohe and acknowledging the fashion industry’s contribution to the world’s waste by trying to mitigate his labels environmental impact. Garments from Kākahu Hou also breathe new life into old cloth. Both collections are emblematic of Luke’s style—light, flowing fabric with a distinct gathering and fit. It is also “a layered response to memorialising grief that tied in matrilineal concepts and ideals that rematriation aided a healing process.”7 Like Lukes garments, this grief is both old and new. In this exhibition, all works are hung along a single clothesline in a no-nonsense display befitting their maker.

Bobby Luke, Whiri Kawe, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Screened alongside the garments are two short films. Whiri Kawe was filmed in Tangahoe awa and Taiporohēnui Pā—spaces of significance for the Taranaki tane. This work epitomises the artist’s expertise in weaving together the interdisciplinary film and fashion design practices he has become known for, bringing to life garments in a way that simply hanging them in a gallery cannot. Whiri Kawe begins with the sporadic sounds of a bell and rapidly changing shots of Luke's young niece Carlida Te Awhe methodically washing an apron in Tangahoe awa. This awa is of huge historical importance to Ngāti Ruanui as a site to gather kai, harvest plants and defend the pā. More recently, discussion of the awa has been focused on its water quality. The environmental impacts of intensive dairy farming is felt all over te taiao, causing devastating effects to the Taranaki region and those who have ties to it. As the film's score begins, we see Carlida standing barefoot in the middle of the road leading to the marae. She walks to the wharekai, putting on and tying the apron herself, for there are no other people to lend a hand. This, as with all of Luke's garments, drapes beautifully across her body. Fabric sourced from his homestead in Taranaki reinforces the whānau centric approach that is also seen in the framing of Carlida’s next movements. Referencing a photograph of tūpuna kuia from Parihaka c. 1890, Carlida stands outside Taiporohēnui wharenui, sombre expression on her face. In another frame, the soundtrack intensifies as the camera zooms out to reveal that she is positioned underneath the waharoa—a lone figure, emblematic of all the wāhine who have stood here before her and will after her. Luke states that the meaning of whiri kawe as a three-strand plait informed his methodology for both the film and collection, as “these threads acknowledge the essence of the past, present, and future”8 In Whiri Kawe we witness each of these threads being tied together just as that apron is tied behind Carlida’s back.

Bobby Luke, Whiri Kawe, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Vince Ropitini, The Art of Passive Resistance, 2023, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Vince Ropitini’s collection, The Art of Passive Resistance, is inspired by the influence Parihaka has had on contemporary Māori art and investigates how it is reflected in fashion design. Ropitini has painted since he was a child and grew up with a desire to be a visual artist. Attending a screen printing workshop opened his eyes to new possibilities and he found that fashion was a way to draw his interests in painting, historical and contemporary protest and punk movements together. In this collection, Ropitini reconnects with his Taranaki whakapapa by using text he has found in his research that references Parihaka, including waiata, as well as iconic imagery of the Maunga and raukura. The patchwork, badges and distressed nature of these garments are representative of the current generation of Māori artists and activists who are staunch and unapologetic about their place in Aotearoa. Mindful of his footprint on the whenua, Ropitini has sourced fabrics from deadstock, second-hand or donations. He also uses dye techniques similar to customary Māori processes, ensuring stylistic cohesion and environmental safety at once.

Vince Ropitini, The Art of Passive Resistance, 2023, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Stemming from his desire to repair the disconnect between himself and his culture, Ropitini has researched Parihaka, a site of immense historical significance to his own iwi that has become emblematic of peaceful resistance and colonial injustice in this country. This research, combined with his use of fashion activism, has informed this body of work. In Kaka-aku, a selection of the garments from this collection have been spaced out around the gallery and hung from black clothing line wire from the ceiling. A long grey coat with Taranaki maunga and raukura painted on the back makes a bold statement at the gallery’s entrance, while shirt and suit jacket pieces covered in text and badges float around the space. Ropitini asserts that the patchwork in his garments “parallels the diverse range of whakapapa connections that constructed the collective identity of Parihaka.”9 This, as with other stylistic decisions such as the use of colour, layering of text and distressed fabrication reference the artist's influences Ralph Hotere, Selwyn Muru, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. In addition to the garments from this collection, Ropitini made a blanket for this exhibition as a way to tie the textile works of his collection to the tīvaevae and quilt shown alongside it. This blanket was draped across a shirt, reminiscent of iconic photographs of men sitting cross-legged at Parihaka, shrouded in their own blankets as they passively protested the razing of their land. Uri of Taranaki migrated to Te Whanganui-a-Tara, where The Art of Passive Resistance trailer shown in Enjoy’s screening room was filmed by Camden Jackson. Despite being 330 kilometres away, when conditions allow Taranaki maunga can be seen at this filming location in Makara, showing just how large he looms.

Vince Ropitini, Ask That Mountain, 2023, installation view. Image courtesy of Ted Whitaker.

Kaka-aku considers the ways in which Māori and Moana artists acknowledge customary practices while constantly adapting. It may seem that there is a vast gap between the art forms of tīvaevae and kākahu, yet looking closely, all artists in this exhibition are exploring the overarching themes of ancestral knowledge and shared connections. It is in these shared strands that Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan, Rosalie Koko, Bobby Luke and Vince Ropitini honour their ancestors while generating new ways of working.

-

1.

Lana Lopesi, False Divides (Te Whanganui-a-Tara: BWB, 2018), 60.

-

2.

Ioana Gordon-Smith, ‘Anything But Shy: Exhibitions of Tīvaevae’ in Pacific Arts Aotearoa, edited by Lana Lopesi (Tāmaki Makaurau: Penguin, 2023), 94.

-

3.

Communication with the artist, 29 August 2024.

-

4.

Susanne Küchler and Andrea Eimke, Tivaivai: The Social Fabric of the Cook Islands, (Te Whanganui-a-Tara: Te Papa Press, 2010), 6.

-

5.

Küchler and Eimke, Tivaivai: The Social Fabric of the Cook Islands.

-

6.

Te Manawa Museum, “Stitching a portal to whakapapa”, 16 December 2022, https://www.temanawa.co.nz/2022/12/16/a-portal-to-whakapapa/.

-

7.

Communication with the artist, 10 September 2024.

-

8.

Bobby Luke, “Kākahu Hou: the Breath of Cloth” PhD thesis, Auckland University of Technology, 2021, https://hdl.handle.net/10292/14808), 318.

-

9.

Vince Ropitini, ‘The Art of Passive Resistance’ Fashion Design Research and Development, 2023, 3.