Exhibition Essays

What Would I do Without You

September 2012

Testing Endurance of Tyrannical Performances

Mercedes Vicente

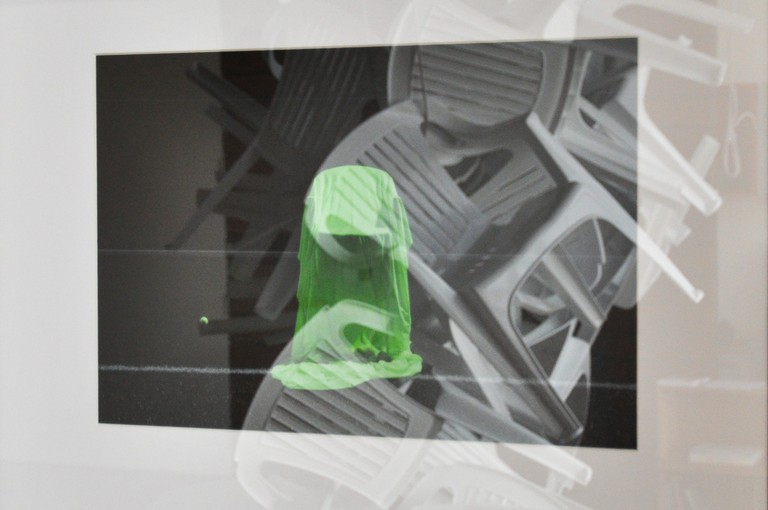

Walking into Enjoy Gallery to visit Daniel Betham’s What Would I Do Without You, the photograph placed in the far right corner of gallery caught my attention. Something about the composition of a deep green cloth covering a chair brought to mind an early Gabriel Orozco photograph, Comedor en Tepoztlán (Dining Room in Tepoztlán), 1995. A quick Google search proves my memory tricked me as in Orozco’s photograph the chairs are actually yellow and turquoise blue and the green cloth is placed over the table in front of these. But regardless of the striking differences between the two, the association still holds. On the floor beneath Betham’s photograph is a white plastic bucket full of green Champion tennis balls; the same balls also appear loose in the photograph. This is a witty trick, as if the bucket has escaped the frame of the photograph and stepped into real life, while the tennis balls have rolled into the realm of the photograph. Betham’s far more prosaic and deadpan humour clearly differs from Orozco’s arte povera sensibility and his poetic chance encounters and subtle interventions with the sites and objects of everyday life. It thus let me wondering whether Betham’s staged photograph/installation might be a pun on Orozco’s work, perhaps he placed the bucket with tennis balls to incite a vandalized attack to his photograph (or the chair, the green cloth, and the whole “Orozco”-like composition!).

Alongside this photographic/installation work, a large bundle of outdoor plastic white chairs takes over a significant central space of the gallery. Strung up by a rope and hanging precariously from a ceiling beam with the aid of two pulleys, all the chairs, but one, hang just above the floor. Some of them are shattered as if they had been smashed against the floor. Next to this installation, close to the wall behind, are two flat screens suspended above head level from a beam (using the same ropes and pulleys), and a third central screen placed on the floor, facing up. All three feature short videos involving the plastic white chairs performing various tasks, so clearly these (together with the tennis balls) are the protagonists. In the first video closer to the gallery’s entrance, a similar number of chairs, each suspended by their legs caught in a wire fence, get mercilessly knocked down by gusty winds one by one, falling on the (green) grass at the bottom of the fence. The proximity of the chair installation to the videos prompts me to wonder if the installation is the detritus of this video performance or perhaps the result of other events that had been previously enacted at the gallery.

As in the videos, Betham’s sinister absence as the orchestrator of these unseen forces is echoed in the exhibition, with Enjoy Gallery acting as the stage for these wicked performances. The videos act as indexical records of an activity involving the same objects that has no narrative in and of itself other than a narrowly confined set of performative parameters. They look like endurance tests assessing the chairs’ ‘fitness’ or determining the amount of time each of the chairs can maintain an activity before becoming ‘fatigued’ and coming to a stop. Relentlessly submitted to these perverse boot camp games, they eventually break, sink or get knocked down. Some tasks are measured in groups to determine which chair performs the greatest endurance (as with the chairs hung from the fence); others are performed individually to assess the greatest amount of a strenuous activity the chair can endure (being thrown up in the air). These arbitrary tests of sheer physical stamina and hardship seem purposeless, bordering on the absurd, as no specific goals seem to be set for the chairs.

The whole exhibition, although extravagantly ridiculous, exudes diligence and control: extra ropes are neatly rolled and objects are precariously set, yet hold just fine (suspended chairs, bucket nearly bursting with tennis balls, a seemingly knocked over flat screen monitor on the floor, etc). All elements have been thought through precisely and economically. A very tight consistency operates between the installation, the videos and the photographic work. The elements bounce off one another by a considered choice of recurrent objects (chairs, tennis balls) and colors (white chairs, white bucket, green balls, green grass, green cloth), matching formal elements of presentation (videos and chairs hanging by the ceiling beams using same pulleys and ropes), and repeated associations between performance and detritus materials. Each element of this exhibition exponentially activates the other and solicits parallel narratives, however irreverently meaningless these may be.

Betham’s ironic take on endurance remains deliberately light and devoid of the radical politics of the 1960-70s era performance works of artists such as Marina Abramovic, Chris Burden or Yoko Ono, who investigated its ethical and political implications. His slant is rather expected from a generation brought up around self-help books, high performance sports, advertising slogans and consumer brand goods.

In a time of crisis, endurance may be a sought after advantage, or perhaps, Betham posits a mocking critique of an ever growing cult of bodily devotion, where the vulnerable or unfit don’t stand a chance. Everything about Betham’s new work seems to be encapsulated in a line from the poem on the flyer written by Lauren Redican, “when your performance is the performance, your performance is everything”—something bordering the tautological.