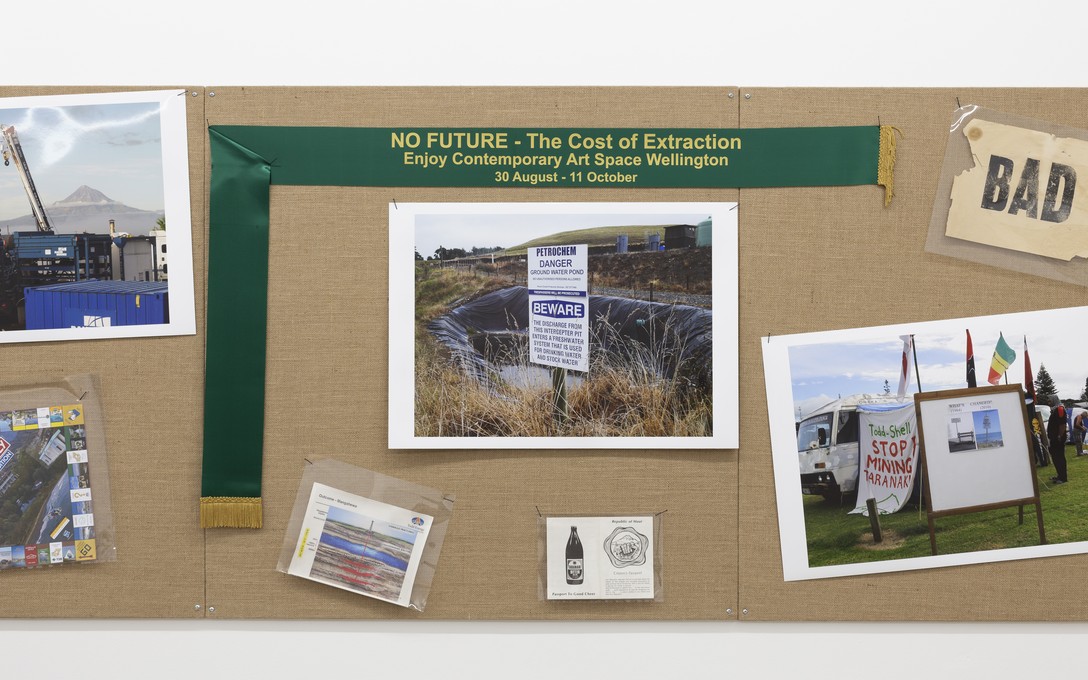

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

archived

30 Aug

–

17 Oct

2025

Elvis Booth-Claveria, Fiona Clark, Hamish Garry

My mum reckons the ground beneath Taranaki will collapse one day and we’ll all fall into a hole. My dad says that the local gas and oil industry fracking the land provided jobs where many were lost due to the closure of the meat works.

The fossil fuel industry in Aotearoa is more than an economic engine, it is a continuation of colonisation. When British surveyors first carved lines across whenua in the 19th century, they transformed a living, relational landscape into something that could be measured, owned, and sold. Today, the digital successors of these surveyors such as Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) datasets, GPS grids, and seismic maps continue this logic, guiding drilling rigs to the next profitable pocket beneath the surface. What was once mapped to be farmed is now mapped to be mined.

Oil and gas exploration in Aotearoa is tethered to global flows of capital and control. Multinational corporations operate with the support of a government keen to attract foreign investment, and with it, the illusion of economic stability. This alignment with Americanised models of extractive capitalism are deregulated, privatised, and often opaque. This can be understood as a form of recolonisation, with the sovereignty of the whenua subsumed once again by outside interests, this time through market mechanisms rather than muskets. Fracking sites are frequently established on or near pā and urupā. At the entrance to Methanex, one of the largest petrochemical facilities in Taranaki, a carving by Albert Tamati from 1982 depicts tractors, gas clouds, and heavy machinery encroaching on the landscape. Below it, a gold plaque reads: “The treasure of the land will persist – humans will not.” It hangs like a warning, or perhaps a confession, acknowledging the violence of extraction even as the business of extraction continues.

The cost of this model is carried in our bodies and in the air we breathe. Flaring towers spit carbon and carcinogens into the sky. Fracking drills into aquifers, displacing water and injecting chemicals. Cancer remains the leading cause of death in Aotearoa, often unspoken and untraced. In the waiting room of the Methanex offices, a glossy Men’s Health booklet sits on the table, offering guidance on how to spot early signs of cancer, a quiet acknowledgement of the risks that linger in the air outside. We are taught to be grateful for the jobs, to be quiet about the headaches, the tumours, the tremors, the grief. “The local benefits will be enormous!”

And all of this occurs in a world on fire. As the climate crisis deepens, Aotearoa continues to pour resources into fossil fuel infrastructure, a move that is contradictory and violently short-sighted. Emissions from these industries accelerate global warming, fuelling the floods that wash through our homes and the seas that chew away our coastlines. The land itself is giving way through slips, sinkholes, and increasingly volatile storms. Globally, the picture is just as stark: armed conflicts have surged by 66% in the past three years. Since 2023, 59 states have erupted into war – the highest number since 1946. Military spending continues to climb, rising 10% annually to reach the highest levels ever recorded. In the face of planetary collapse, the engines of extraction and violence grind on.

NO FUTURE – The Cost of Extraction brings together artists who are listening to the land and registering its wounds. Fiona Clark’s Gaslands project is anchored in decades of photographing and responding to the oil and gas industries that dominate Taranaki. Her photographs and footage of gas flares, fracking sites, and the people who work within them capture not only the extensive industrial violence of these operations, but also the quiet endurance of communities living under their shadow. In performances such as Listening to Fracking (with Raewyn Turner), Clark attends to the subterranean tremors of whenua, reframing penetration as a deeply gendered and violent intrusion into land and body. From a lesbian perspective, her work subverts the patriarchal coding of penetration as conquest, instead proposing a model of contact grounded in reciprocity, attention, and consent. Her new performance What would this space look like without fossil fuel company sponsorship? shows Clark shackled and circling the Todd Energy-sponsored Len Lye Centre in Ngāmotu New Plymouth. The work speculates on what the art sector in Aotearoa might look like stripped of oil and gas sponsorship, asking what cultural ecosystems could emerge if art refused to be underwritten by the industries accelerating planetary collapse.

In January 1995, a major well blowout occured in Tikorangi, the result of a pressure kickback at the Mckee 13 well. It was eventually contained with 127,000 litres of mud and 68 barrels of quick-setting concrete, but not before wiping out 1,100 metres of the nearby Mangahewa stream with oil and drilling mud. The declared threat zone extended 10 kilometres. Fiona Clark recalls being visited by authorities at 6pm, who had waited for locla farmers to finish milking their cows before warning residents to stay indoors. Roads were closed for three days. The risk of an explosion would have obliterated everything within that 10km radius, including the town of Waitara itself. This lived proximity to disaster threads through Clark's work, grounding her photography and performance in the everyday realities of risk, negligence and survival in a petrochemical landscape.

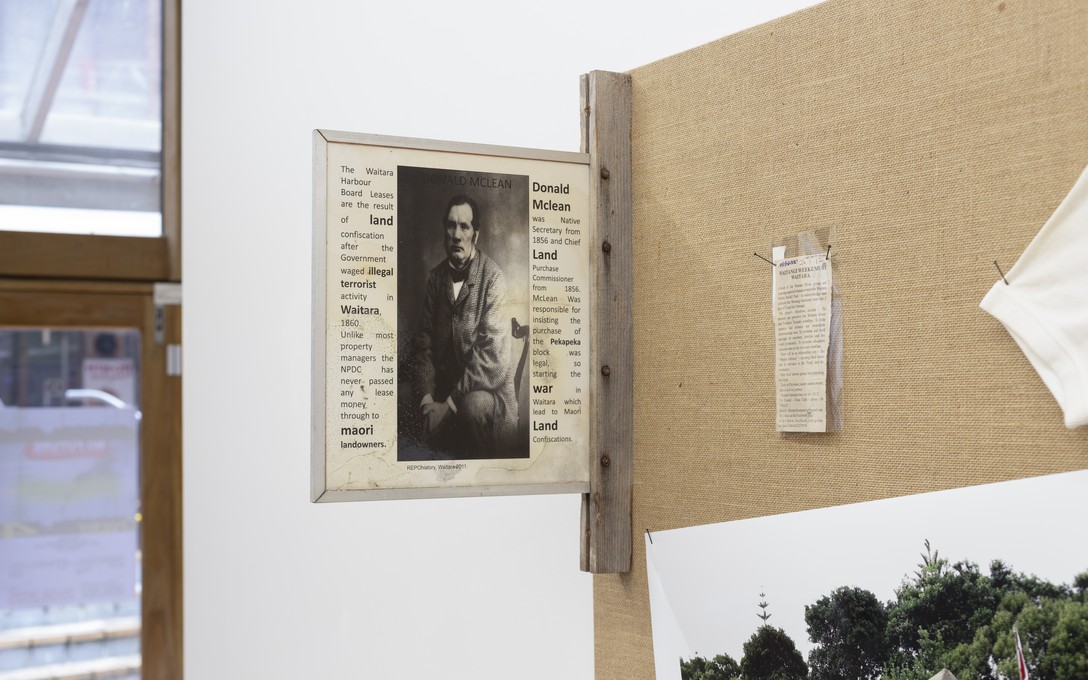

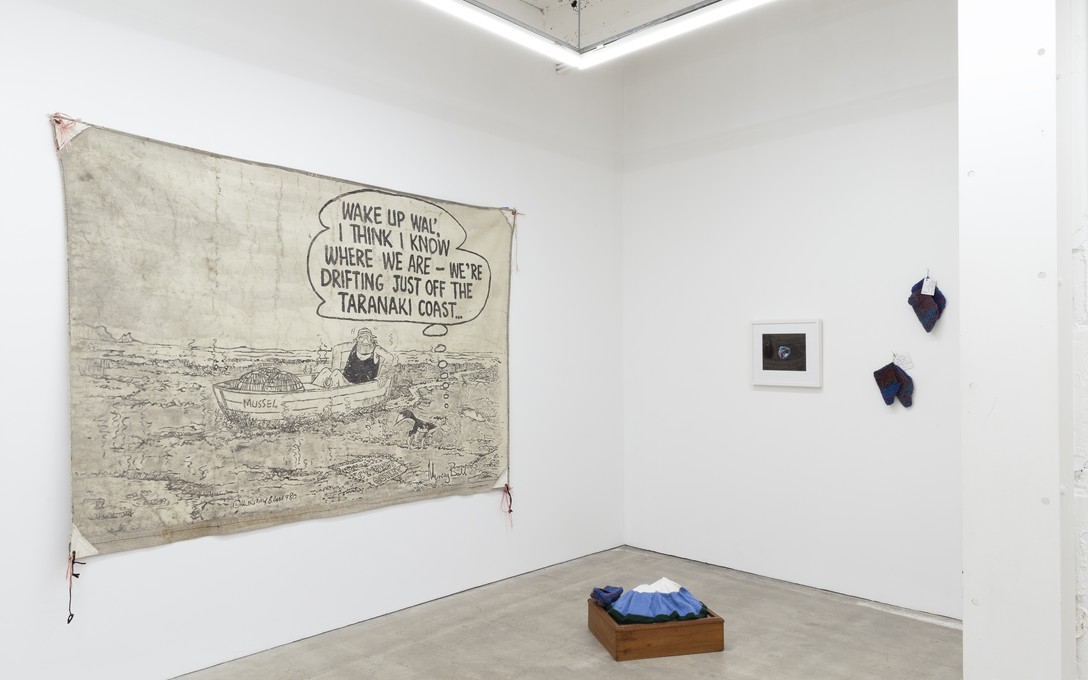

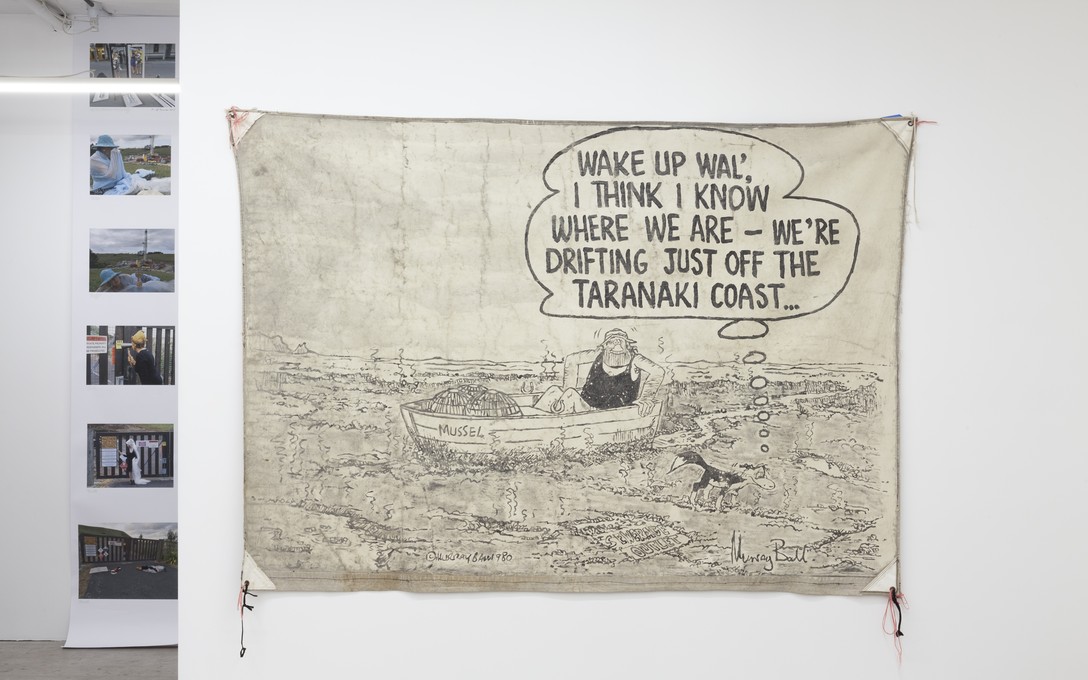

Clark’s longstanding practice in Waitara also examines the colonial signage that still honours British military figures who seized and divided the land, now mirrored in the Americanised street signs marking new suburban developments. This visual continuity speaks to the persistence of a settler logic that treats whenua as a commodity under changing empires. Through The Waitara Project, Clark worked alongside local communities to protest the fossil fuel industry’s pollution of the Waitara River and foreshore. Together they created and installed banners – some by residents, others by artists such as Murray Ball – calling out the poisoning of the environment and the erasure of local sovereignty. This embedded, collaborative approach positions Clark’s art as both witness and weapon, a practice that records what extraction takes away, while actively participating in the resistance to it.

Elvis Booth-Claveria explores the entangled violences of extraction, colonisation, and identity through performance. Responding to Fiona Clark’s performances and documentation of fracking, they treat the land as a confidant, gossiping into the earth as though it might whisper back the buried truths of what has been taken. Their metaphor of the whenua as a queer, wounded body – infected, leaking, pimples popped – rejects the sanitised language of “resource management” and instead embraces an animistic, embodied process. Booth-Claveria reflects on how colonialism is inscribed not only on the land but within the settler body itself, calling for a reckoning that uses presence and vulnerability to unsettle place-based norms and make visible the intimate economies of extraction.

Booth-Claveria's video installation Wells: Gas, Wishing, Tear and Fare is an inquiry into what it means to stay, to remain present in a damaged place, and to inhabit relation as a form of care. Drawing on transness as a praxis for understanding life as tangata Tiriti, Booth-Claveria embraces the unsettled, the shifting, and the accountable as a means of being with the land. In dialogue with Scott Herring's Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism, their work asks how hope might be found in staying-with, enduring proximity, and recognising that not everyone is entitled to leave. By examining how the industry is imposed upon the body (desire without care, consumption without maintenance), they expose the uneven politics of extraction and mobility, showing that presence itself can be both a burden and a radical act of solidarity.

Hamish Garry’s 4.4°S, 172.8°E – 41.6°S, 178.6°E confronts the mechanisms of ownership encoded in colonial state apparatuses. Using Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) data, Garry has created a to-scale model of Te Ika-a-Māui, a surveyed terrain that recalls the early cartographic tools of empire. His model illustrates how the land has been fragmented into commodifiable units for settler possession, material extraction and, more recently, for offshore investment and speculation. Through the reanimation of LINZ’s 'neutral' data into a sculptural presence that evokes museum and planning maquettes, Garry’s work invites touch and connection to whenua, while interrogating the techno-legal instruments of dispossession that shape the colonial present – instruments that now extend the dispossession of Aotearoa into the digital and globalised realm.

By making the model touchable, Garry disrupts the distance and abstraction through which land is usually encountered in maps and data. Touch collapses the gap between body and territory, implicating the viewer in the act of handling surveyed land while also opening the possibility of care, intimacy, and reciprocity. What does it mean to hold a surveyed fragment of Aotearoa in one's hands? In extending access to an object that represents dispossession, Garry's work stages a tension between the violence of measurement and the haptic desire to connect, reminding us that whenua is not an abstract grid but something lived with, felt, and continually negotiated.

Together, these artists refuse to normalise what is deeply abnormal: that land can be owned, that bodies are disposable, that a future is only available to those who can afford it. Their work asks us to hold the full complexity of this moment, the grief, the complicity, the longing for something otherwise. Because there is something otherwise.

Curated by DJCS

Past Event

LAUNCH: NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction

Join us from 5pm on Rāmere Friday 29 Heriturikōkā August to celebrate the launch of our fourth exhibition chapter, NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction.

More info

Fiona Clark, Gaslands and The Waitara Project, REPOhistory, Waitara, 2011. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

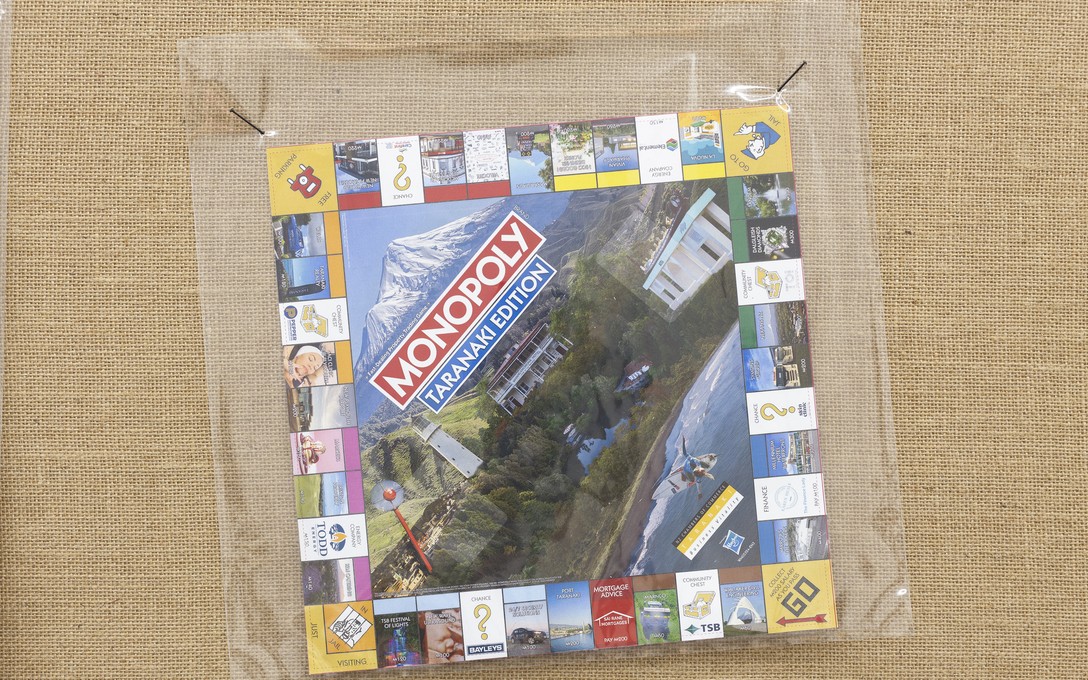

Fiona Clark, Gaslands and The Waitara Project, MONOPOLY Taranaki Edition. Released 2025. New Zealand Chamber of Commerce. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, Gaslands and The Waitara Project, Maui Crude Oil, 1963. Bottle by New Plymouth West Rotary Club. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, Gaslands and The Waitara Project, various works. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, Gaslands and The Waitara Project, Mustang Drive, 2025. Polaroid 600. Where the American based fracking companies HAILBURTON and George Bush's BAKER HUGHES are based, Bell Blcok. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Margaret Ann White, Taranaki Maunga, 2019. Slippers knitted by Fiona Clark to match Taranaki mountain, 2025, titled Farcking Slippers or Little Mountain slippers, named by Margaret. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Hamish Garry, 4.4°S, 172.8°E - 41.6°S, 178.6°E, 2025. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Hamish Garry, 4.4°S, 172.8°E - 41.6°S, 178.6°E, 2025. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Hamish Garry, 4.4°S, 172.8°E - 41.6°S, 178.6°E, 2025. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

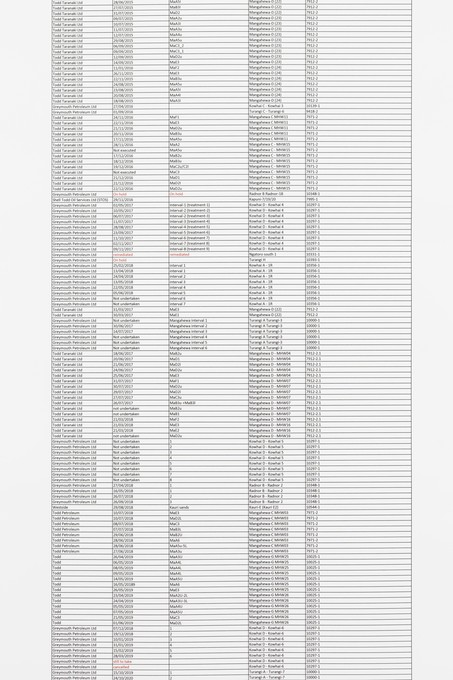

Fiona Clark, list of hydraulic fracking activities, 1989—2025. The 550 records do not include well blow outs or oil spills. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Ruby and Pearl (Fiona Clark and Raewyn Turner), Listening to the ground for fracking, 2017. Mangahewa A well site, Todd Energy (left), Kowhai A well site, Greymouth Petroleum (right). Performance documentation. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark's private gas supply burning in her kitchen, Tikorangi. Fiona Clark, compilation of various well sites with a record of their exact distance to Fiona's house, representing the zone in which she lives. Gas flares, men preparing to frack, thumper trucks performing seizmic surveys. Ruby and Pearl (Fiona Clark and Raewyn Turner), Listening to the ground for fracking, 2017. Mangahewa A well site, Todd Energy, Kowhai A well site, Greymouth Petroleum. Performed during a high period of fracking. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Elvis Booth-Claveria, Wells: Gas, Wishing, Tear and Fare, 2025. Multi-channel video installation. Filmed at the decomissioned Pōuri A well site, Tikorangi. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Elvis Booth-Claveria, Wells: Gas, Wishing, Tear and Fare, 2025. Multi-channel video installation. Filmed at the decomissioned Pōuri A well site, Tikorangi. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Elvis Booth-Claveria, Wells: Gas, Wishing, Tear and Fare, 2025. Multi-channel video installation. Filmed at the decomissioned Pōuri A well site, Tikorangi. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

NO FUTURE - The Cost of Extraction. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, What would this space look like without fossil fuel company sponsorship? 8am 10 August 2025, New Plymouth. Performance documentation: 03:30. Detail view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, What would this space look like without fossil fuel company sponsorship? 8am 10 August 2025, New Plymouth. Performance documentation: 03:30. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark, What would this space look like without fossil fuel company sponsorship? 8am 10 August 2025, New Plymouth. Performance documentation: 03:30. Installation view. Courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Fiona Clark

Taranaki-born Fiona Clark (1954-) is one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s most celebrated art photographers. Since completing her Diploma in Fine Arts (Honours) at the University of Auckland Elam School of Fine Arts in 1975, Clark has spent more than five decades photographing the people and places around her. Working in a social documentary style, Clark’s artistic practice engages with the politics of gender, identity and the body, and her long-term projects have focused in on specific social groups including transgender and bodybuilding communities. Clark lives and works in an old ex- dairy factory in Tikorangi, Taranaki. She was made an Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi Laureate in 2023.

Elvis Booth-Claveria

Elvis Booth-Claveria (Pākehā, Chilean) was born in Te Papaioea, Manawatū, and is currently based in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. Working between performance, video, sculpture, and installation, their practice moves between land, body, queerness, and atmosphere as an autotheoretical pursuit, and an intimate negotiation with connection, dislocation, and vulnerability.

Their work unfolds through documented performances in which the environment becomes both stage and collaborator, a site where ideas surface in gestures and sensations rather than in linear or verbal form. Passing between states of embodiment and dissolution, Booth-Claveria seeks to encounter the body without hierarchy, unseating the dominance of the head, brain, and mouth over the rest of the system. This iterative process opens a shifting terrain in which queer, colonial, and political identities are neither neatly resolved nor singularly defined, but stretched, braided, and held in productive uncertainty.

Hamish Garry

Hamish Garry is a Dunedin born artist, craftsperson and industrial designer based in Te Motu Kairangi (Miramar, Wellington). Hamish is interested in art as the product of fabrication processes, fashion, material availability, skill and access. His practice explores neutrality, authority, truth, trust and authorship, while playfully teasing at the definition of an art object, through the application of (self-devised and self-enforced) rules for 'automated' art production. Hamish's works highlight both the beauty and fallibility inherent in physical materials and modes of making, as well as digital and data-driven processes. Informed by a long held involvement in exhibition and museum craft, Hamish enjoys accessible, useful objects, whose meanings are formed in relationship with the audience and user.