Exhibition Essays

Aletheia

September 2008

An inward, outward leap

Jeremy Booth

Like a stalled conversation I walked into Aletheia at an awkward moment. The works were silent.

In what can best be described as an un-choreographed lull I experienced Nicholls’ work, first off, as a series of sleek, showroom objects. They were static, still, white, and framed by an expansive deep-blue gallery wall.

Language often relies on timing for effect and the way I first approached the works allowed me room to shift sideways, to experience a moment of chance while remaining sheltered by the limits of experience itself. For the objects soon came to life, moving from a state of rest to one of movement, their structural qualities became stem, frame and support to something more: a concealed energy unfolding beyond the work’s formal modernist lines.

The works installed at Enjoy presented a microcosm of Nicholls’ practice and artistic development. Moving chronologically from a starting point of resolute grounded-ness, to a lighter more architecturally weighted series of forms, the show included early kinetic experiments through to prototypes in devel- opment. Nicholls’ practice, seen holistically, demonstrated an increasing lean towards the linear and a pervasive engagement with sound and form.

Sculptural in nature, the works acted as vehicles or even shells in which a mechanical core could be seen to drive a visual flowering, allowing sound to be perceived as motion. But it would be limiting to focus purely on the scientific facade of the work, like counting the bricks in an expansive wall without stopping to consider what might be on the other side.

The exhibition exerted a weight of technical import, yes. But its self-driven actions were lyrical and denied the rationality of imagined inner-workings. What moved within did come out, but with results that were unexpected from objects ingrained with such logic. The works took a range of physical forms, while at once denying their own expected physicality. They carried an un-crafted mark of same-ness, in that their possibilities were already written, and yet each expanded imposed possibilities of the finite, functioning to take one thing and turn it into another. A transformation took place that somehow left the thing unchanged.

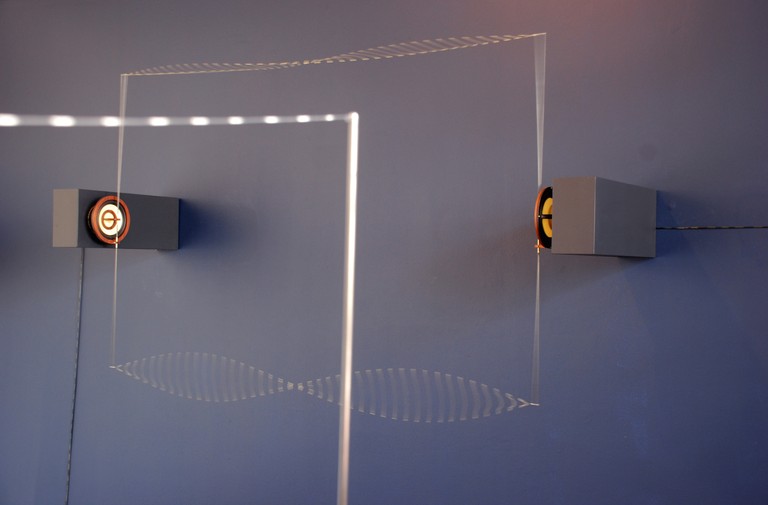

Nicholls’ objects seemed to speak for him, in their own tongue. He simply sculpted and tweaked their vocal chords and provided a loose script—a Kubrick-esque script that re-wrote itself daily. The works were installed so as to exert their physical transformations with the greatest level of clarity: Begeondan with its blue gallery wall; Render, Monofilament and Wire One with their respective contrasting backdrops; and the exhibition in its entirety, in the way its installation allowed for movement, trepidation and the viewer’s close contact with ‘live’ wires. An exercise by the artist not in control, or didacticism, but in framing and pointing towards that which unfolds and thus extends beyond control.

Truth: The German philosopher Martin Heidegger resurrects the term Aletheia from the Greek amid a sea of semantics and over the course of several books.FTN1 He locates it as a central point within the Greek concept of Being: Being; an unfolding of that which ‘abides in itself ’ and Aletheia; the unfolding itself—the moment of revelation. It centres on the idea that something cannot be, until it is revealed, whether in physicality, theory, or in myth; and that conversely, a non-truth is something that remains hidden, or concealed.

‘Truth’ in this sense implies not a bastardised factuality, an inherent good, or coherence, but the moment of an inward, outward leap; the moment of disclosure whereby something that is, suddenly is, again. It suggests a kind of quiet pendula motion in which ‘rest and movement are closed and opened up from an originary unity’.FTN2 This was taken up in Nicholls’work when sounds were being translated into motion while existing as sounds, concurrently.

The polar binaries of Nicholls’ Aletheia—the un-event I walked into, and the frenetic activity I was left to ponder—can be imagined as intrinsically the same. No matter the line that can be drawn at their further- most point, the states swung back, meeting in the middle in a perpetual cycle. Concealment. Revelation.

The furthermost lunges from rest, the many apexes ensured that sound was translated into motion and then, eventually, into physicality itself. The sounds in their varying degrees of audibility, were not only interpreted or shaped or re-interpreted, but also briefly located and revealed as objects in their own right.

Monofilament for example, moved with such energy that it ceased to move at all. A tepid wire drooping between two rods reached a liquid critical mass, being re-positioned as the shape of the sound, or as the sound might appear were it tangible. Like driving past picket fencing and allowing the eye to remain on one point, the pickets become a collective flicker rising and falling with fluidity. No longer the individual objects, but an amalgam of light and movement born through the human eye’s deficiencies: how the pickets may appear when combined with movement.

The eye can only process data so quickly, as a camera’s shutter has limitations, and Monofilament, like the other works, went beyond this as it captured the sounds that drove it, revealing a physical, if ephemeral form. Fundamental to this transformation, this translation, were the conscious crutches of light and movement—inactive in periods of rest—and the fact that someone was there to see it.

Seeing is believing, or knowing. And yet to become known does not always require to be new. Perhaps to be revisited, re-framed or re-presented. Aletheia did not disseminate the new, that is, the unknown. Instead it identified by way of representation that which it already contained. Allowing it to be perceived and received in a different form.

When I first saw Nicholls’ work I was told that it would map ‘the perceptual space where sound and movement converge’.FTN3 This was apt within the darkened, spacious, ex-provincial cinema galleries of the Govett-Brewster, and of Nicholls’ practice as a whole. Standing amongst Aletheia though, in the unashamedly white and more intimate Enjoy Gallery I found that sound was not given motion or physicality, that these qualities were not forced to converge, but instead encouraged to shape, account for, and sculpt each other.

Light provides the means for a photograph in an inversion of representation. The works in Aletheia also created, by way of inversion, something to see: something more tactile, palpable and easier to point a finger towards than their more excitable, concealed referents.

A manual Single-Lens-Reflex camera contains all of the elements needed to give physicality to light— to render an image of that which the light beyond it falls upon. And yet the image already exists as an object or scene, if only fleetingly, in front of the camera. Beyond the operator’s ability to manipulate the medium, as Nicholls did in creating the audio, building the works and positioning them in dialogue, the camera doesn’t add or subtract from that which it captures. It can however borrow, interpret, and reveal it in a different state. This makes it easier to contemplate, study and appreciate; and by being stem to its objectivity, testifies to the fact that it does exist even if beyond human perception.

Deficiency played a large part in Aletheia, and it was largely on my part as the viewer. My ears couldn’t hear the inaudible infrasound, and my eyes couldn’t separate the wires’ collective motion. Aletheia’s steal threads bridged these scarps in their perpetual becoming and brought them out of the shadows and into the field of representation.

Recently I spoke with a dancer whose playful distaste for the visual arts arose from her inability to figu- ratively reproduce what lay in front of her, in the way that she intended. I began to see that an adherence strictly to what we see or perceive, often renders the most interesting elements negligible. Truth is an elusive concept in art and Nicholls’ Aletheia suggested that it doesn’t need to be pinned down in order to be present. A process of ‘capturing’ can be more one of re-presenting and re-forming, where change and chance create and reveal space for meaning.

-

1.

Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927), and Introduction to Metaphysics (2000) being the key and seminal texts.

-

2.

Martin Heidegger, Introduction to metaphysics: New translation by Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (Tübingen, Max Niemeyer Verlag, 2000), 63.

-

3.

Tyler Cann, Double Harmonic: Len Lye & Tony Nicholls (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery), 3.