Exhibition Essays

and my heart is soft

April 2018

Ka mate kāinga tahi, ka ora kāinga rua

Heidi Brickell

|

Whakataukī |

proverb or saying |

Tāniko |

a type of Māori weaving |

|

Rākau |

tree or wood |

Pou whakairo |

ancestral carving on a post form |

|

Dida |

Grandfather |

Nana |

Grandmother |

|

Wānanga |

an explorative mode of thinking involving deconstruction, meditation and connection |

Whare tupuna, wharenui, whare hui |

meeting house for a hapū that represents a the body of an ancestor and the history of the hapū |

|

Haeata |

a opening to light, literally, a tear in the dawn |

Ka hoki mahara |

go back in the mind |

|

Te Ira Tangata |

the first human, the original gene combination |

Ātua |

god(s) |

|

Raupatu |

seizure of land from its unconsenting guardians |

Tikanga |

way of doing things, custom |

|

Reo |

speech, language |

Pounamu |

greenstone, also bottle, since their glass resembled the colour and translucency of the stone at the time of their christening in te reo |

|

Manuhiri |

visitors, new comers |

Toa |

warrior |

|

Tangata whenua |

custodians of the land |

Whānau |

family, nuclear or extended |

|

Aramoana |

path to the sea |

Tauiwi |

foreign settlers |

|

Aroha |

love |

Pekerangi |

outer walls of a pā |

|

Muru hara |

grace, forgiveness |

Rangatira |

Chief |

|

Manaakitanga |

generosity, care, hospitality |

Taonga |

treasure |

|

Ngākau |

heart |

|

*Note: In te reo Māori, nouns are pluralised by surrounding words, in an English context, plural form is implied by context |

Ka mate kāinga tahi, ka ora kāinga rua

A first home dies, a second home lives

This is the first of a series of whakataukī brought to my mind in contemplation of And my heart is soft, an installation of objects through which Bronte and Ange Perry consider heredity.

The whakataukī speaks of resilience and improvisation, on the one hand. It is commonly applied to any situation in which a ‘plan B’ is required, or when one system gives way to another. On the other hand, you could consider how it illustrates a life cycle understood within an ontology of whakapapa: what it means to identify as te kānohi ora: the face, or eyes, of the living that are seeing, representing and speaking in a moment bracketed by birth and death, within long chains of descent. Each body born of an ancestor is a house that lives and dies for the DNA residing there for a time.

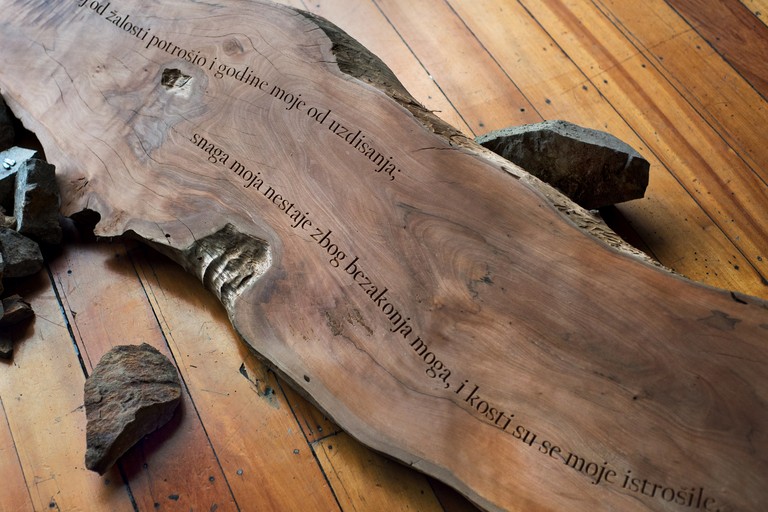

Kauri, pohutukawa and punga lie strewn among rocks on warm siennas, caramels and umbres of the Enjoy gallery floor. The large area of warm colours has a gravitational pull, dragging your eye towards the floor. Just above head-height hang two woven tāniko. They are raupō, muka, white, black, with fragments of pāua tied into their tassels. They keep lifting your gaze again, suspending your attention between the two sets of works. As your eyes scan between them, the gridded shadow and the fluttering shades reflected through the windows of a moving city outside infect your overall apprehension of what is installed in this enclosure. Negative space that links the two artists’ contributions to this exhibition. It makes me think of Rangi and Papa, and the light and the outside that ruptured their union. But plural symbolic dimensions are at play here.

![Ange Perry, Dida, 2018, muka, paua [above]; Bronte Perry, Nikola Kršinić I, 2018, Pohutukawa [below]. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.](/media/cache/1a/8f/1a8f2c593a93b6ae00c958e37fd8c55e.jpg)

Ange Perry, Dida, 2018, muka, paua [above]; Bronte Perry, Nikola Kršinić I, 2018, Pohutukawa [below]. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

Overlapping subjective addresses

The doubling up of subjective positions is evident in the titling of the works by each artist. Ange’s hovering tāniko are titled Dida and Nana, Croatian nicknames for Grandfather and Grandmother. Bronte’s pohutukawa works are titled Nikola Kršinić I and Nikola Kršinić II, and their kauri works have been given the names Tangi May I and Tangi May II. Investigation into the artists’ whakapapa reveals that Tangi May and Nana are the same ancestor, as with Nikola Kršinić and Dida, each embodied twice here under the invocation of their respective descendants.

Ngā kōkona o te whare e kitea, ngā kōkona o te ngākau e kore e kitea

The turns (corners) of a house are seen, but the turns of the heart are unseen.

This whakataukī primarily serves as a caveat against taking a person or social situation at face value. I bring it up here, though, because it is so embedded in the everyday reo Māori I know that it also lays out a foundation of associative schema: it pairs a metaphor of a house as an exterior together with a metaphor of the heart for an interior psychological space. Associations between a whare and a psychological space are drawn in Mason Durie’s model for a Māori psychological practice in Te Whare Tapawhā, loosely translated, “the four dimensions of the house.”1 The overlaps between house and home, whare and kāinga, interiorisations and exteriorisations of body and belonging are synaptic fusions embossed in this Māori speaking brain. And due to this, with all the other referents operating too, I can’t help but feel that in some conscious dimension, a personal whare tipuna—representing a smaller progeny—is being imagined, reconstructed, rebuilt.

The references speak through fragmented and simultaneous constructions. In a wharenui, pou whakairo represent specific ancestors, while the tāniko that link them express life principles. The works in And my heart is soft, rather, avoid literal reproduction of the cultural forms they call out to, distributing equally across their mediums the functions of connection, remembrance, and contextualisation that they seek to access; both woven muka and carved rākau represent vessels through which to touch face with earlier iterations of a code and the experiences that have been imprinted on it, the artists’ DNA; both bear motifs and symbols of significant events.

In wharenui to which you belong, you listen, you speak, you debate, you chorus, and you sleep surrounded by images that you remind you who you are through complex contingencies of bloodlines, histories and once and sometimes again, fluidly evolving epistemologies. It doesn’t delimit, it just lays out all the sources. The new constellation of forms and symbolic functions presented by these artists emanate personal journeys that make their own ways on and off the radar of the utterable and recognisable.

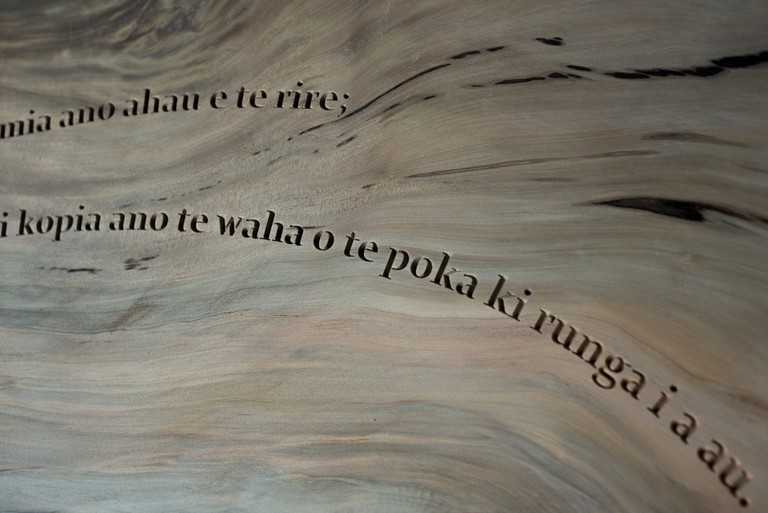

The ink-black tāniko here is shaped like a maro worn by the daughters of rangatira, and depicts the motif aramoana, indexing everyday pursuits and pleasures of Nana/Tangi May. The white muka weaving integrates the yellow leather case that covered the plum wine pounamu brought to this land from Croatia, which came to provide Dida/Nikola’s means of escape from a harsh and hostile life to which he had never intended to find himself moored. The ancestral rākau slabs, each split again into two per tupuna represented, are carved with curvilinear script, in Croatian and Māori translations of biblical passages that uncurl across them like ngā raurū o kurumatarērehu—the curved (tāmoko) spirals of those who have woven together people and histories through their networks, feats and travels.

For manuhiri first embarking on a marae, stories housed in the abstractions adorning a whare will be shared, extending their insight into wider territories via the specific lenses of the tangata whenua. The personal references retold hereafter, which include a mixture of fact and speculation, hopefully contribute an illumination of the complex impacts of colonial processes unfolding in this whenua to the individuals who are products and agents within them.

Ange Perry, Nana, 2018, muscle shredded harakeke, muka. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

Theatre of historical memory and empathy

Neither rākau nor tāniko are ordered with the rhythmic, evenly spaced conventions of a whare tupuna, but more in accordance with a contemporary sensibility that emphasises process and improvisation. The agglomeration of an ancestral whare is invoked through the displaced symbolic functions. The resilience of the body or the brain when one organ will reinstate the functions of another that has been lost or rendered incapable, echoes. There is a concurrent register of uprooting and exodus. The fidelity of the artworks to natural materials, lying among unaltered punga and quarry stones which swarm around the rākau, half propping some of them up, and turning one into a makeshift seat bench, seems to simultaneously replicate an outdoor scene, a worksite. The diagonals of the half propped up slabs give a sense of movement, slippage, destabilisation, as does the v-shaped arrangement of Nikola I and II, which open towards the interior space and draw perspective lines receding towards the window and the outside space. Ka hoki mahara… something like a historical memory.

The inscriptions weaving across the four ancestral rākau read, respectively:

Jer se život moj od žalosti potrošio i godine moje od uzdisanja; snaga moja nestaje zbog bezakonja moga, i kosti su se moje istrošile.

(For my life is spent with grief, and my years with sighing: my strength faileth because of mine iniquity, and my bones are consumed. Psalm 31:10)

Kua ringihia ahau, ano he wai, kua takoki katoa oku iwi; me te ware pi toku ngakau, e rewa ana i waenganui i oku whekau.

(I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint: my heart is like wax; it is melted in the midst of my bowels. Psalms 22:14)

Ne udaljuj se od mene; jer je nevolja blizu, a nema pomoćnika.

(Be not far from me; for trouble is near; for there is none to help. Psalm 22:11-21)

O tamariki i whakakorea mau, tera ano ratou e mea ki o taringa, E kikī ana te wahi nei moku: whakawateatia atu, kia noho ai ahau.

(The children you will have, After you have lost the others, Will say again in your ears, ‘The place is too small for me; Give me a place where I may dwell. Isaiah 49 New King James Version)

Paired with fragmented pieces of ancestors, plotted out as a map of intergenerational trauma, opaque and yet evidently re-experienced through the subjectivities of the new skins, both reiterating and rewriting what has been passed down genetically, epigenetically or culturally.2 Each inscription could just as easily apply to what either ancestor likely felt throughout major disruptive events and their aftermaths during their own life journeys.

Bronte Perry, Nikola Kršinić II (detail), 2018, Pohutukawa. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

Nikola came to Aotearoa in the 1940s to work in quarries, escaping civil war in what was then Yugoslavia (also known at times as Croatia or Dalmatia). The life of tauiwi not welcomed by the Pākehā majority was a lonely one. Reasons for mutual Māori and Pākehā hostility stemmed from a few factors, such as the prodigious work ethic for which Croatians were renowned,3 as well as their willingness to endure miserable working conditions that had been established during the earlier ‘gold fever’ for Kauri gum in Te Tai Tokerau that had attracted a first wave of migrating Croatian labourers from 1850 onwards, a decade after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Joanne McNeil illustrates the kind of existence they lived:

...gumdiggers worked inhumanly hard, often in foul circumstances, their only crime a kind of blithe hope. Most were single men; most lived in small huts made of timber, sod, and corrugated iron. Some lived in shanties made from grain sacks.

At day’s beginning they would walk several kilometres to the patch they were digging. Often they worked in water as they searched the wetlands and peatlands, working down through the rich deposits of sediment, soil, and decaying vegetable matter which had been carried down with the gum from surrounding hills. While several men dug holes, another operated a primitive hand-pump made of makeshift piping—sometimes jam tins soldered together. Most of the holes were one to four metres deep, but groups of diggers sometimes worked 12 metres underground.4

Tangi-May’s own bloodline incorporates an ancestor, ‘Benzine George’, who had come here during the first wave of Croatian migration to Aotearoa. Imagery inscribed on her rākau of both the self and the fluids expelled from a body in fear could reflect the displacement of Croatian expulsion from seized land as equally as it could Tangi May’s Ngāti Rangi ancestors from their kāinga at Ngawha pā, Ōhaeawai, when it was besieged by British troops in 1845 under Colonel Henry Despard, devastating a dwelling place for the hapū. In this light, the split rākau, scattered among debris, also speak to violence and annihilation.

The Ngāti Rangi rangatira, Heta Te Haara, commissioned Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere, an Anglican Church, erected in place of the whare tupuna which had stood before as a symbol of peace and forgiveness when the land was later returned to the hapū’s hands.5 An urupā commemorating both the Pākehā and Māori toa who lost their lives in that battle was also designated around the new whare. The stone walls that now surround it stand in the exact place that the pekerangi of the old pā had stood. A kāinga rua, that, while constructed and commissioned by Māori for Māori, has adopted the appearance and, to some extent, the functions of a Pākehā whare and institution, feeding its codes to and being written into by the ngākau and hinengaro of Ngāti Rangi hapū. Successive generations saw the religious denomination housed within Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere reincarnated through Māori Anglican to Seventh Day Adventist, eventually to Jehovah’s Witness at the time these two artists departed from the ideological body, and, as a consequence, from connection with the whānau tying them to their taha Māori.

When Nikola migrated here in the 1940s, World War II had turned Germany and any association therewith into a key target for distrust. Croatian association with the German-speaking Austro-Hungarian empire meant that suspicion also fell on them, as potential spies. Not welcomed in Aotearoa, and not intending to stay, Nikola’s long term residence with Tangi-May was never made socially acceptable through marriage. But this wasn’t due to a radical rethinking of patriarchal norms. It was rather a refusal to recognise the permanence of his geographical affiliations and the economic stasis anchoring him to them. It’s hard from the place, time and context I occupy to imagine the extent to which overt intolerance and publicly tolerated cruelty towards those outside of narrow models for normalcy were themselves norms, only a few generations prior.

It’s known that unmarried status with an outsider to both Māori and Pākehā communities brought shame and social punishment upon this woman of mixed Māori and English descent trying to assimilate into a whitewashed culture and its sexually repressive interpretations of the Christianity. It’s known that their daughter, the link in the chain to these artists, wound up a bitter and violent woman, also a prisoner of alcoholism. Successive generations of Ange and Bronte’s family struggled to sustain connection to the Christianised meeting house and the community it fostered at Ōhaeawai pā.

Whether and to what degree infiltration of Christianity into Māori tikanga and spirituality represents a loss of Indigeneity within Māoridom continues to be debated. Many see the religion as an apparatus of colonisation to replace Indigenous epistemologies: a raupatu whenua of the mind. Others argue that Māori relationships to Christianity have been agentic, appropriating the knowledge and tools bought here by Pākehā to serve Māori epistemologies and ends, as an anti-colonial force.

Bronte Perry, Tangi May II (detail), 2018, swamp Kauri. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

My own lifelong pursuit of a Māoritanga diluted through generations intersected with my relinquishing a Christian faith that formed the schema of my universe until my early twenties. A decade and a half later, with the understanding that the retitling of a landscape happens much faster than the gradual processes of transforming its infrastructure, I have an enduring interest in the question. Increasing involvement in Te Ao Māori contains many familiar and comforting elements for me that crumbled away after I denounced Christianity.

One key encounter that prefaced my nominal severance with religion was with a book called The Primal Vision: Christian Presence amidst African Religion.6 Written as a challenge to the arrogance and hypocrisy of English missions in Africa, where its author, Bishop John V. Taylor grew up, the ideas in the book have relevance to Aotearoa. Colonial approaches to disseminating religion, and Indigenous cosmologies that seem more proximate to those of the writers of the biblical texts on which Christianity is founded resonated with my own grasp on Māori cosmology and colonialism when I read it. Having tracked down the book again, the observations of this English missionary seem tentative, fair and worthy of relating to aspects of Christianity’s adoption within Māoridom also.

Taylor questions the Western claim to the religious philosophies in the first place. He seeks to understand African spirituality and cosmology in order to enter into dialogue about religion with the people in whose country he resided. He comes to criticise the ahistorical assumptions of English Christians that their own Anglican practices, based upon a religion of Middle Eastern origin, were universally legitimate interpretations of the faith. His criticisms of the way the Christian mission in Africa went about converting Indigenous peoples to the faith sounds to me similar to how a narcissistic abuser creates conditions in which they will later be able to assume the role of rescuer to their victims.7 First befriending with flattery and gifts, then, once trust is gained, incrementally tearing down the power, independence and subsequently the self-efficacy and esteem of their victim. At first, this is done in subtle and underhanded ways that a person not accustomed to their motivations and methods lacks the prior knowledge to identify. The victim is set up to fail, or framed as failing according to a new set of criteria imposed by the abuser (such as monogamy, or genital modesty in art forms). As the failure scenario repeats, the victim is framed to look increasingly incompetent, if possible, discredited in front of others, garnering a consensus to deny their perception of reality. Being unable to articulate and identify the reasons for their dispossession, it is difficult for the victim to reject blame for what happens to them. Without the experience, and therefore, vocabulary, to name what is happening, the victim comes to internalise the belief in the inferiority projected onto them. As an abuser gains confidence, the injustices and hypocrisies become more overt, as their victim becomes so unsure of their perceptions that they begin to accept the narratives they are fed by the abuser. In this state, a victim, believing themselves to have lost their capacity for self-governance, comes to believe that they need rescuing by their apparently thriving abuser and becomes willing to relinquish control over themselves.

On the other hand, Taylor argues that African worldviews8 have affinities with those expressed in the Eastern texts of the Bible; whereas the literal-rational and individualistic character of Western world views may preclude access to the intentions of The Bible’s writers. Aspects of the Indigenous African cosmology Taylor discusses share elements with Māori worldviews. Narratives of the Bible unfold upon a basis of whakapapa, as do its symbolic implications for the overturning of old political hierarchies.9. This philosophical structure through which its messages are communicated aligns more naturally with Māori thinking than with the universalising point of view of Western liberal democracy. In the liberal democratic worldview, emphasis is placed on individual rights, severing associative identities from the streams of code which write an individual with the borders of their bodies, however, The Old Testament is full of concerns for future and prior generations.

Bronte Perry, Nikola Kršinić I and Nikola Kršinić II, 2018, Pohutukawa. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

There are many who interpret the broad spread of Christianity within Māori settings as an extension of Māori autonomy within living and evolving communities of cultural practice.10 Hīrini Kaa argues that its adoption has been through processes of Māori agency, as an intellectual opportunity, in the democratising technology of the written word that came with The Bible11. Access to the ideas contained in its books offered a vocabulary through which to criticise the Pākehā State. Additionally, as Māori knowledge was often encapsulated in the poetic, a less literal and more symbolic appreciation might have afforded better insight into the text—such as the creation stories of Genesis, the pluralistic wisdoms expressed in Proverbs, and the allegorical nature of Revelations.12 The rising up of prophets among Māori across different iwi, using reinterpretations of the ideas brought to them by missionaries is evidence of an identification with the intellectual material in accordance with Māori interests. Prophets such as Te Whiti o Rongomai, Tohu Kakahi, Rua Kēnana, Te Ua Haumene, Te Kooti Rikirangi, and Te Atua Wera all led ideological movements that appropriated Christian texts to engage in resistance against colonial warfare.

As a product of a particular Christian upbringing myself, both positions ring true in part with my own experiences. The ideological framework I was brought up with emphasised a strong distinction between the ethical and legal, and encouraged psychological preparation to stand at odds with mainstream culture. It provided intellectual means to critique authority. In spite of the toxic social encapsulations it has been shared through, at its core are principles of aroha, muru hara and radical manaakitanga.

At the same time, I recognise the damaging encouragement of self-sabotage. In teachings that honour self-sacrifice, Christianity doesn’t equip those who take it to heart to defend their taonga against individualistic cultural values so intrinsic to Western epistemologies. It took me many years after severing my own affiliations with the faith to recognise the depths of repressive self-policing I had internalised from its emphasis on humility-as-inferiority and the perpetual witch-hunting for evil inside oneself and one’s companions. Through those mechanisms, I see Christianity’s potential to be a vehicle to castrate the disenfranchised.

Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal emphasises the fluid continuity that was Māori knowledge up until its suppression and partial erasure by colonising processes, encouraging Māori revitalisers to understand themselves as active participants in the evolution of Mātauranga Māori, as it comes into contact with other knowledges. In the case of these two artists, the infusion of religious orthodoxies turned their spiritual homeland into a place that suffocated them more than it nourished them and so, they let go of their kāinga tahi. Through the art practices shared in the Enjoy space, precious and dynamic explorations for how their lines of heredity might be cultivated afresh as kāinga rua, are in process.

Ange Perry, Dida (detail), 2018, muka, paua. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon.

Formal echoes of a Māori genesis

The two readings described earlier imagined visits to the contexts that shaped the psychological dispositions passed down through Croatian, Māori and English bloodlines, and a mihi to a meeting house that would have been an inheritance, fragments of a map put together. Overarching these interpretations is the spatial proposal made by the floor and sky arrangement of work, with viewers sandwiched in between, shadows of a world outside the one occupied, flickering on the blank walls. It creates a dynamic expressed in the whakataukī:

Kōtahi noa iho te ātua Māori, ko Ranginui e tū atu nei, ko Pāpātuānuku e tākoto nei.

There is only one Māori God, the sky above and the earth below.

-

1.

Mason Durie’s “Te Whare Tapawhā was developed in 1984 at Hui Taumata in response to Rapuora, a piece of research undertaken 1978–1980 by the Māori Women’s Welfare League that uncovered the issues and barriers Māori were experiencing in health. These experiences had led to disengagement with health professionals and were resulting in a declining health status—the primary barriers were around the lack of spiritual recognition and perceived racism. Te Whare Tapa Whā became the conceptual framework to support health practitioners improve their engagement with Maori and for spirituality to be more readily acknowledged.” Te Whare Tapawhā is a widely recognised model for Māori health within Te Ao Māori and academia. “Te Whare Tapa Whā: Health as a Whare” Tane Ora Alliance, accessed October 10, 2019 https://www.maorimenshealth.co.nz/te-whare-tapa-wha-health-whare/.

-

2.

For a fascinating discussion of epigenetics, see Robert Sapolsky’s Stanford lecture series on youtube, particularly: Robert Sapolsky, “Molecular Genetics I.” Lecture, Stanford University, California, April 5, 2010, accessed 4 October, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_dRXA1_e30o&list=PLZV0bNLmkCYPYh3w0VXAaSPEaoF2sVz5D&index=5&t=0s, and Robert Sapolsky, “Molecular Genetics I.” Lecture, Stanford University, California, April 7, 2010, accessed 4 October, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFILgg9_hrU&list=PLZV0bNLmkCYPYh3w0VXAaSPEaoF2sVz5D&index=5.

-

3.

Joanne McNeil, “Northland’s Buried Treasure,” New Zealand Geographic 10, (April 1991), accessed 4 October, 2019 https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/northlands-buried-treasure/.

-

4.

Ibid.

-

5.

Bronte Perry “In the Shadow of Te Whare Karakia o Mikaere” (Honours essay, University of Auckland, 2017): 11.

-

6.

John V. Taylor. The Primal Vision; Christian Presence Amid African Religion (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1963).

-

7.

I have paraphrased and elaborated on his description of power relations with the analogy of abusive dependency relationships, drawing on private testimonies of relationships with narcissistic abusers. Taylor, The Primal Vision, 135-138, 150-151, 162.

-

8.

Taylor’s generalisation of pan-African world views are qualified throughout the book, acknowledging the need to lean on a generalisation for the context of his criticism, acknowledging differences across African groups, but recognising shared epistemologies as distinctive from Western ones. The problematic of grouping and terminology is also discussed in the introduction by J.N.K Mugambi. Taylor, The Primal Vision, xix-xxxv.

-

9.

For an in-depth discussion of biblical structure based on whakapapa see Cameron B. R. Howard, “What’s with all the begats?”, Enter the Bible (blog), August 1, 2013, accessed October 4, 2019 http://www.enterthebible.org/blog.aspx?post=2646.

-

10.

In this use, Christianity is meant in the broadest possible sense, without wanting to clutter up the essay with qualifications.

-

11.

Kaa, Hīrini. “He Ngākau Hou: Te Hāhi Mihinare and the Renegotiation of Mātauranga, c. 1800–1992” (Doctoral Thesis, The University of Auckland, 2014). 24, 30.

-

12.

A powerful example demonstrating how sophisticated geographic methods already developed by Polynesian explorers closer to 1000 BC, fields now generally considered "hard sciences," were naturally communicated via metaphor is the way the expanses of the North and South Islands of Aotearoa are retained in popular memory as articulated as Māui's fishing up of a stingray, the North Island, from his boat, the South Island.