Exhibition Essays

Caressing the silver rectangle

May 2017

Intimacy and Alienation in the Techno-Human Era

Nina Dyer

Meditating on the intimate facets of modern technology, the group exhibition Caressing the silver rectangle considers how these may reflect aspects of ourselves—or fail to, as is the case in erroneously presumed identities and misdirected target marketing. Centred on the nature of increasingly humanised technologies, the works in the exhibition hint at the more sinister, commerce-driven reasons for personalised user interfaces, revealing the habits we form as a result of emotional attachments to digital media.

The exhibition takes its title from Jesse Bowling’s installation, which consists of an enlarged replica of an Apple laptop’s highly tactile, scratch-resistant track pad; a screen displaying a webpage automatically refreshing through seemingly infinite lines of code; and a memory foam Bambillo®1 supporting said screen. While some think of Apple products as excessively sleek and impersonal, Bowling instead considers the sensory intimacy produced by technology developers to appeal to our universal desires for comfort and connection. One is instantly linked through their device to other people—they’re not inanimate machine objects, but rather like live appendages of the self. The ensuing attachment we develop towards our devices is irreversible; the more intelligent and personalised our devices appear, the more inseparable from the individual they become.

Jesse Bowling, Caressing the silver rectangle (detail), 2017. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Apple has recently enhanced their track pad design with ‘taptic’ technology, a play on the concept of haptic interaction. The taptic engine creates a textural feedback system that causes laptop users to feel an illusory clicking sensation when they press down on the pad, when what they are really feeling are vibrations emulating the sense of depressing the pad.2 This allows not only for a more weightless device, but one that integrates tactile responses to movement. If haptic technology advances, Apple laptop and iPhone users will be able to ‘feel’ things on their screens like words and icons, transforming our digital experience into a more sensual one. The goal is to increase physical and mental oneness with ‘smart’ devices—where ‘smart’ is the operative word for developers aiming to make consumers more adept at carrying out mundane functions. The rhetoric of a smarter future appeals to a cyborg ideal, where the limited genetic makeup of human users is aided by the super-human efficiency and vast information resources our external devices offer.

The cyborg appeal is not lost on Transhumanists—a collective who believe technology and science will allow humans to evolve beyond our biologically limited conditions.3 The most extreme advocates of this philosophy are biohackers, a branch of the body modification movement whose members experiment with ways to literally incorporate technology into their physical makeup. The Transhumanist movement can be seen as sympathetic to the (implicitly marketable) ideology of big data companies—Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook—that invest in technological developments. Innovations in tech are said to advance humankind, with these companies attempting to predict the next step in techno-human evolution before we realise something is holding us back… even something as trivial as having to get out of a chair to alter the volume of a music device. The belief of both Transhumanists and companies invested in technology is that humanity will fall behind as machines progress—that we must incorporate technology into our everyday life and become electronically-extended cyborgs if we wish to transcend the human condition. Despite having no commercial interest in technological advancement, the ideologies of personal data collectors could also be seen as symptomatic of the ideals espoused by big data corporations, embodying the marketing ideals of these companies.

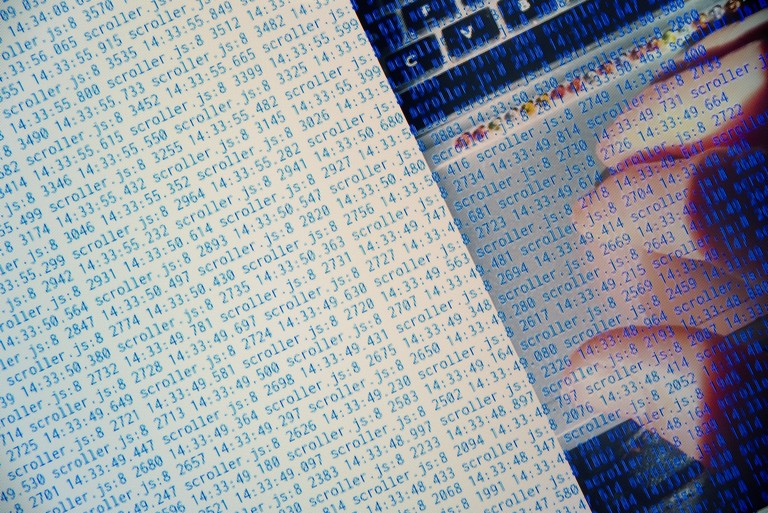

Jesse Bowling, Caressing the silver rectangle (detail), 2017. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

The code moving along Bowling’s screen is personal data collected on an app, designed with Sean Burn, which records the artist’s scrolling movements and presents them as a series of numerals and semicolons—indecipherable, but nonetheless signifying the recorded actions for those who know what it is they’re looking at. In visualising his scrolling habits this way, Bowling was interested in learning something about himself through the self-monitoring of his absent-minded internet use. While it’s not clear what can be learnt from the data presented, this type of seemingly redundant collection is typical of the interests of data collection communities. Participants vary from people recording patterns in their Google searches to members of Quantified Self—a movement working towards human perfectibility through “self-experiments” with recorded data.4 Quantified Self members tend to be guided by medical interests, with typical experiments monitoring blood pressure or hormones. However, like the ‘smart’ fitness trackers Fitbits, the information gathered is rarely combined with any directly practical application. The motives of individual data collectors differ, but their sometimes inane experiments hint at some larger cause for the phenomenon. Perhaps a certain anxiety is produced by the thought of large amounts of data being automatically amassed as we move through cyberspace, without our conscious recognition—something akin to the loss of control felt when one thinks too long about where daily waste goes, with the background knowledge that it piles up somewhere out of sight.

Due to the partially incorporeal nature of digital media, materiality is a challenge faced by artists working with internet-era subjects. Despite this, it can also be through the act of materialising digital phenomena that the nature of techno-cultural relations can be perceived from a different perspective—an alternative angle from our everyday interactions with the internet and the devices we take for granted. Bowling’s creation of an artwork from tracked data can be seen as a parallel to the desires of individual data collectors who visualise and curate their presence on the internet. Within Caressing the silver rectangle, the process of concretising data is extended beyond the digital sphere and into physical space. By forming a body of code that externalises his digital movements, Bowling physical manifests his activity on a screen for others to see. His movements are not only displayed online but re-materialise in present time and space—the information collected on his scrolling activity is recorded instead of simply being absorbed by the internet.

Maddy Plimmer, Tired of sleeping alone? Maddy Plimmer (detail), 2017. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Where does our data go once it has entered the ostensible void of the internet? Is it stored in some immaterial store hold of memory like we imagine the Cloud to be, or is it really mined in physical industrial complexes, owned and secured by big data companies? It makes sense to desire control over one’s personal data when massive corporate bodies are surveying our movements, using them to tap into our commercial interests in order to manipulate the information and advertising we’re exposed to online. It’s disconcerting to imagine that the habit of searching for old friends on social media, in times of loneliness or boredom, is stored in a digital file somewhere in Silicon Valley because an airline company might want to offer me flights to my hometown at a discounted price. It would seem that self-surveillance offers a sense of agency amidst this mass data-mining scheme, of possession over one’s personal and emotional habits.

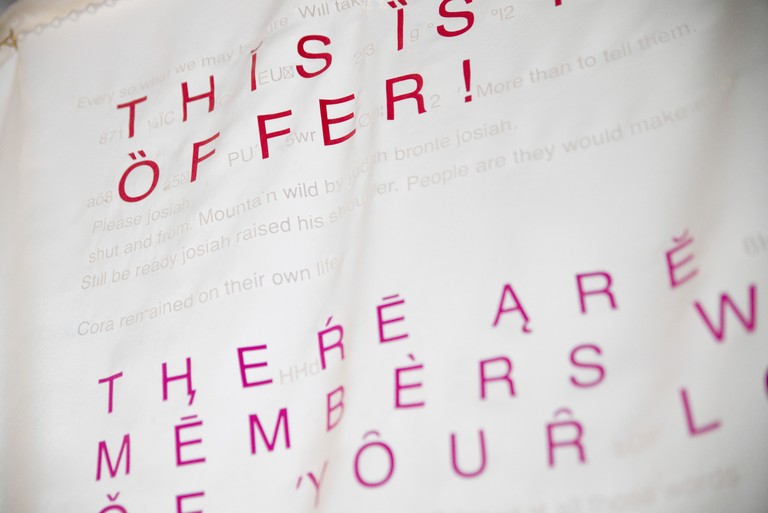

Maddy Plimmer also considers how online commerce appeals to the desires of touch, ownership and attachment, both in regard to her source material—spam emails promising to gratify one’s sexual needs if they just click the deceptive link offered—and the objects she has made in response. Hanging from the gallery ceiling, four imposing sheets of material are printed or embroidered with the language and typefaces drawn from spam emails. With titles taken from the subject lines of these emails (such as Tired of Sleeping Alone? Maddy Plimmer), these texts are designed to offer visions of satisfaction and intimacy, though their disingenuous origins in ‘phishing’ practices are betrayed by the inclusion of nonsensical sentences and accented letters, automatically programmed in the hope spam filters cannot distinguish them from genuine emails.

Phishing relies on social engineering to succeed in attaining personal information. These kinds of ads curiously identify gendered stereotypes in an attempt to assume exactly the weaknesses of their target audience—vanity, sexual impotence, or income. Plimmer’s work highlights a trend in spam, where advertisements addressed to her are often mistakenly aimed at a distinctly male desire, recommending drugs for erectile dysfunction for example. During the artist talk for the exhibition, Plimmer questioned if this is because the default internet user is thought to be male, an indication that the internet is no different from any public space, created for and dominated by masculinity (as opposed to private, domestic spaces which are typically gendered feminine). This realistic view of the internet is far from the genderless, classless and raceless utopia envisioned in Donna Haraway’s 1985 essay A Cyborg Manifesto.5 The cyber-sphere has inherited the publicly suppressed views of humanity’s most prejudiced individuals, who find their voice in online communities where anonymity allows for impunity. The prevalent bigotry of the web is reflected in experiments where unsupervised Artificial Intelligence chatbots were conditioned to learn and respond to conversations online, only to spit back the most offensive and problematic views of its users.6 If the space of the internet were a virtual nation, perhaps Plimmer’s banners could stand in as flags, where a dominant identity is catered to but those at the margins of society are alienated.

![Louise Lever, It is sounds that lives in her, 2017 [left], Maddy Plimmer, On the verge of breakage, because you cannot satisfy her? (II), 2017 [right]. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.](/media/cache/54/e4/54e4b8377a86b87bc19930dfec65ccdf.jpg)

Louise Lever, It is sounds that lives in her, 2017 [left], Maddy Plimmer, On the verge of breakage, because you cannot satisfy her? (II), 2017 [right]. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Walter Benjamin wrote of the loss of ‘aura’ that takes place when a mechanical reproduction is made of a physical work of art, but what happens when the found image has already been disseminated online and the reverse of mass production takes place?7 Like Bowling, Plimmer effectively materialises the immaterial, taking a digital file intended to be widely circulated and turning it into a physical experience. Enhancing the enticing design of the spam emails through visual and tactile decisions, Plimmer creates a corporeal experience out of the found digital media—her banners require one’s immediate presence for their sensuous nature to be considered. They are at once evocative and cheap, the satin thin with raw edges. Most of the banners are physically out of reach, just like the elusiveness of their false invitations to ‘meet locals’ or find happiness.

By highlighting the kind of quasi-realities we encounter online like the too-good-to-be-true personal adverts, Plimmer’s installation could be read as an implicit warning against investing too much in an online sphere. Her banners humorously mimic the hit-and-miss assumptions of spam emails, but the work’s undercurrent is one that draws attention to the way in which we bring our ‘real’ identities with us when we engage with the internet; extending a reality already structurally inhabited by hyper-masculinity to the online sphere. The freedom of the internet is a positive democratising feature that can circumnavigates censure, but this inevitably comes at the expense of a cyber safe-space of the kind imaged by Haraway. The social hierarchies of gender, race and class are thus enabled and able to proliferate, unchecked, online.

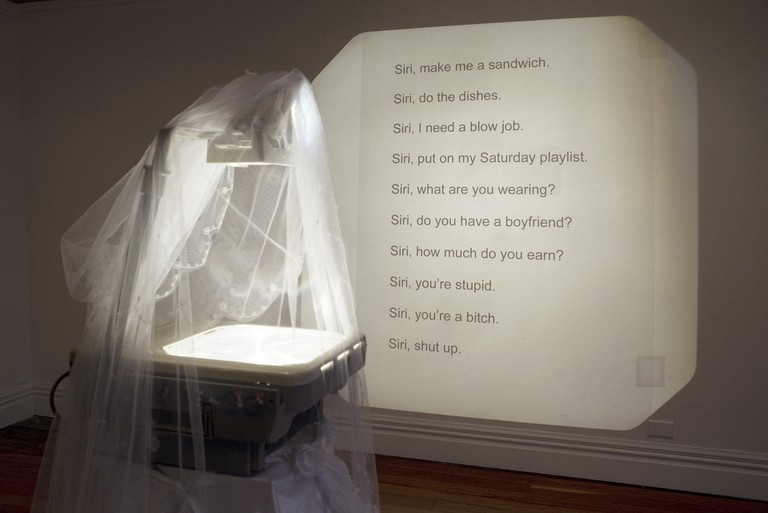

The third work in the exhibition, It is sounds that lives in her by Louise Lever, highlights certain behaviour towards Apple’s intelligent voice assistant Siri. Here, the female gender assumed by Siri’s voice is considered in relation to a default male iPhone user. Siri takes the place of subservient female who talks back, but with limited agency. Lever’s installation mimics the false sense of intimacy instilled by Siri’s creators, who design humanised voice assistants to make devices more personal and interactive. The idea is to increase emotional attachment to devices by incorporating ‘smart’ assistants that memorise their user’s preferences and details, forming a bond over time as the app learns more about its user through each interaction. However, in Lever’s work, Siri’s users seem to prefer objectifying the voice assistant.

Louise Lever, It is sounds that lives in her, 2017. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

An overhead projector casts a list of requests and statements addressed to Siri, which Lever found on the internet and reiterated in a projection of the most telling verbal provocations. The list ends in abuses like ‘Siri, you’re a bitch.’ Lever’s collection of gendered requests points to a history of belittling female assistants, especially where the lines between woman and object are blurred. Artificial intelligence has been anthropomorphised and gendered since its inception in science fiction. The projector wears a wedding gown and veil, a possible reference to the fictional Stepford Wives. Lever cites the film Metropolis (1927), as a point of departure, the earliest instance of artificial intelligence on screen that set the trend for female androids in literature and film. In Metropolis, the android answers to her creator and is made in the image of a femme fatale, using her seductive powers to bring down the city. Unlike her more subservient fictional descendants however, this early fembot speaks in a way that is much like Siri and its clever retorts, pre-programmed by writers to maintain the facade of intelligent interaction. The android of Metropolis is ultimately called a witch and burnt at the stake, culminating in a cautionary and gendered tale of artificial intelligence, one that coincides with the period’s attitudes towards women claiming increased agency in society.

It seems that the conception of non-human intelligence in literature and film reflects the anxiety of male audiences; fictional female androids (post-Metropolis) are typically offered up in palatable, degraded versions engineered to please to the male gaze and serve his needs, but without the complaints, emotions or rights of a real female personality. Thus, an AI like Siri can be treated however a male wishes to treat a woman, but without the consequences that come with demeaning an actual human being. The ethics of interaction are altered under these circumstances, because despite AI’s tendency to be given human characteristics, we supposedly appreciate that they’re only machines programmed to appear so. Why is it then that a collaborative study carried out by J. Walter Thompson and Mindshare revealed that over a quarter of frequent voice assistance users have projected sexual fantasies onto their assistant?8 Perhaps lack of subject agency brings out the worst of our uninhibited desires.

A typical reason cited in defence of gendered voice assistance is that people are more likely to perceive a male AI as a threat—a view that feeds back into popular culture’s depiction of destructive male androids. Indeed, robots engineered for military situations have adopted hyper-masculine qualities, while those geared for assistance or the replacement of roles in the hospitality industry are typically given female names and personalities. A similar trend is observed in human systems engineer Andra Keay’s study of gendering in robotics competitions.9 Reading Lever’s installation along these lines, the treatment of gendered technology demonstrated here seems to support the thesis that the role of language significantly informs our thinking and behaviour—while simultaneously absorbing attitudes and biases through its use.10 Linguistic determinism thus adds another layer of responsibility to the design and naming of smart devices and artificial intelligence. Technologies such as voice assistance or chatbots like Microsoft’s Tay speak the language of their designers initially, but their intelligence largely relies on unsupervised learning; most of what they have to say is sourced from the internet. As these applications become more integrated into our lives and further inform our perception of the world, it is of even greater concern that women are severely underrepresented in AI development agencies. Where females comprise an average of 14 percent of the key roles in the tech industry, their absence is even more apparent in the AI sector.11

As technology evolves within this male-dominated industry, it is imperative to evaluate the features of the devices we encounter everyday and our interactions with them, in order to gauge where ‘smart’ technology is heading—and where it’s leading those who use it. It seems that the rhetoric surrounding technological developments promotes the ideal of evolved techno-humans, where intimate bonds formed between user and device are viewed as a means of enhancing both the human body and human intellect. By augmenting applications and devices with human characteristics, consumers more readily accept the alterations made to their lives that new technologies require; to adapt more naturally so to speak. Regardless of the commercial interests that breed these ideals, generation Y is overwhelmingly invested in a more technologically immersive future, with each new innovation or smartphone upgrade being quickly absorbed into the cultural logic of millennials. Caressing the silver rectangle probes the question of whether an increasingly techno-human era is such an ideal existence after all. As more tactile and humanised designs engineer further physical and mental attachment, desires still fail to be met and identity politics and prejudice remain inescapable, foregrounding our interactions at the interfaces of technology and sociality.

-

1.

"The Original 8-in-1 pillow," Bambillo, https://bambillo.co.nz/the-original-8-in-1-pillow/.

-

2.

“Apple’s Haptic Tech is a Glimpse at the UI of the Future,” Wired, last modified March 19 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/03/apples-haptic-tech-makes-way-tomorrows-touchable-uis/.

-

3.

“What is Transhumanism?,” accessed May 29, 2017, http://whatistranshumanism.org/.

-

4.

"About the Quantified Self," Quantified Self, http://quantifiedself.com/about/.

-

5.

Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (London: Free Association Books, 1991).

-

6.

“Microsoft’s Disastrous Tay Experiment Shows the Hidden Dangers of AI,” Quartz Media, accessed 11 June 2017, https://qz.com/653084/microsofts-disastrous-tay-experiment-shows-the-hidden-dangers-of-ai/.

-

7.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 520-527.

-

8.

“Speak Easy: The Future Answers to You,” accessed May 29, 2017, http://www.mindshareworld.com/sites/default/files/Speakeasy.pdf.

-

9.

Anda Keay, “Robot, Slave or Companion Species” (Masters Thesis, University of Sydney, 2011).

-

10.

“Language and Thought,” Linguistic Society of America, accessed May 29, 2017, https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/language-and-thought.

-

11.

"Is AI Sexist?,” Foreign Policy, last modified January 16, 2017, http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/01/16/women-vs-the-machine/.