Exhibition Essays

Other Possibilities

March 2013

Articulate Distance: Christina Read’s Other Possibilities

Julia Lomas

Christina Read’s project operates in the heady, unreal territories of ambition and anxiety. Both of these mental states deal with uncertain and imaginary possibilities, the most threatening spectre in this hazy field of vision being failure. Work that deals as explicitly as this one does in language probably can not avoid a reckoning with the problems that lie in wait, that linger in the space that falls between signal and message. In fact, the passage between the signal and its uptake—the space a message navigates before it reaches its point of communication, is the space I wish to talk about here in terms of Read’s project. This passage—be it temporal (the time it takes for delivery), or cognitive (between speaker and listener) is one loaded with textures and grain. Enlarged, these grains are like the surface of fabric when magnified, something smooth is revealed to be rough, coarse and perilous to negotiate. I propose that this body of work (and it is sort of like a body—the big continuous form, made from materials that mimic leathers or suedes and that wrinkle like skin) exists almost as a speech act, a phrase that hangs in the air. In this case, it hangs weightily, stickily. Read handles this language deftly; it would be easy to approach the work as if it were naïve, a sort of childish approach to the complexities of life, or a therapeutic projec—an attempt at dealing with the angst of art making (or life in general) through the repetitious techniques of occupational therapies—counting off the hours, stacking up time spent in the studio to ward off self-doubt and disquiet. While this may be evident, what really takes shape is a gulf: the gap between sense and sound, the passage travelled in the project of communication.

Read handles this language deftly; it would be easy to approach the work as if it were naïve, a sort of childish approach to the complexities of life, or a therapeutic project—an attempt at dealing with the angst of art making (or life in general) through the repetitious techniques of occupational therapies—counting off the hours, stacking up time spent in the studio to ward off self-doubt and disquiet. While this may be evident, what really takes shape is a gulf: the gap between sense and sound, the passage travelled in the project of communication.

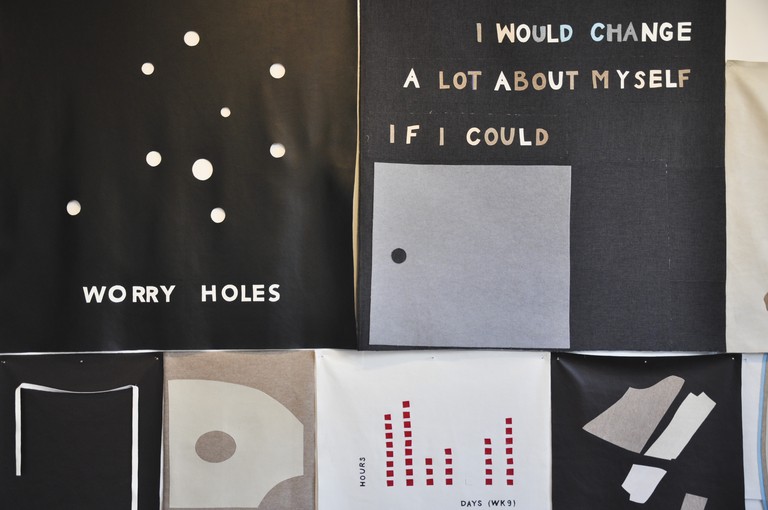

It is this perilous, uncertain course that Read charts in this collection of works. Presented like a patchwork quilt, the works were hung cheek by jowl. There is a panic to it, as if the artist—preparing for the show—set out to make as many of them as she could in the time allowed to her. One got the sense that if there were more of them, the entire gallery wall-space would have been covered. This sense of panic feels more like anxiety than it does hysteria, the nagging sense that one must keep going, keep digging away at a spot until the festering mess that lurks below is revealed. This feeling is also somewhat vindicated in an individual piece that literally maps out chunks of time spent on the show over a week period. The artist refers to this habit of hers quite explicitly in her written account, and it is hard not to feel that perhaps a sense of Puritan guilt (idle hands do the devil’s work) infuses the practice of hour counting.

As discovered in Read’s artist talk, the works have their grounding in the very ordinary trials and rituals of everyday life – the difficulties of new diets, the shock of finding a dead possum in the garden, the nagging sense of worry that bores little holes in the stomach lining. She is matter of fact when it comes to her source material and doesn’t hesitate to reveal the backstory. So what is the ingredient that makes Read’s work more than just a quirky tale about a possum, or a diet, or self-doubt? I sense this goes beyond the freshness of honesty, the equally absorbing source material and the relatively novel use of craft type materials.

Both dreams and nightmares—ambition and anxiety—often turn out to be mirages, imaginary possibilities. The point at which either begins to take on a life of its own, is the point at which a potentiality takes shape. The shapes in Read’s fabric works are suitably oblique and ambiguous, as if to only suggest things, not make them explicit. Looking carefully, I see the hind of the possum caught in what is a rough outline of a yellow trap (the story of which is also narrated in Read’s artist statement). But vague outlines are enough: a threat only needs to be roughly articulated in the distance in order for it to feel real. Suggestiveness is then perhaps the show’s field of operation; its very title is suggestive, always deferring to potential others—other realities, other meanings. Which returns us to language.

It is to interpret the story that Read tells in her artist statement as the narrative of the exhibition itself:

When I came back from my last holiday I was surprised to find a dead possum in the garden near the washing line, trapped in a bright yellow possum trap. It looked like a cat from the back and gave me quite a fright. I was afraid it might still be alive; I didn’t put my washing out that day.

Read narrates fear, confusion, misidentification. It may be useful to approach some of the fabric shapes as a kind of alphabet of forms, characters, or parts of speech. Some hang like quote marks or dashes in the air, others are more solid and difficult to identify. The indistinct forms that Read employs in this body of work are suggestive of confusion, yet her use of blocky, colourful outlines also lends a weightiness to her language: bright yellow, thick fabrics, block lettering, rounded, solid, shapely. While there is an imprecise quality to the way these are rendered, it also conveys solidity, a thickness of presence. This has the effect of making each character feel very present—stubbornly so. And the stubborn presence of these blobby forms enforces a sense of verbal blundering and confusion. Even her typesetting arrangements infer the simplest of failures, as the words awkwardly run over the space allotted to them –

OTHER

POSSIBILI

TIES

This has the effect of forcing the reader to internally sound out the phrase, slowing down its delivery, complicating the meaning. Another text work simply states,

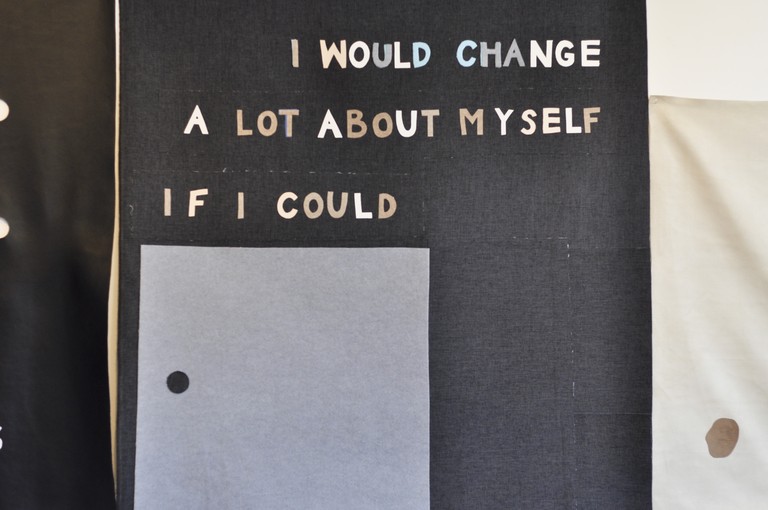

I WOULD CHANGE

A LOT ABOUT MYSELF

IF I COULD

Yet, Read is careful to keep her balance with minimal, elegant gestures—in one piece, a ribbon draped simply over the fabric sits in harmonious composition. She works the point to its neurotic conclusion, but somehow avoids labouring it. We get more than enough to sense nebulous, precarious ideas—the fantasy of self-improvement, the ever shifting goal posts of both what we aspire to, and what we fear, yet these same concepts remain strangely out of focus.

But by contrast, the materiality of each work lends something utterly tangible. The folds, dimples, stretches and creases of the fabric are satisfyingly tactile. The block lettering, the holes that have been cut out, the obvious thick textures of felt, vinyl and denim, all combine to bring about a sense of wholeness, a feeling that the nebulous ideas and ambitions have been made real. There is also a strong sense of personality to the work, obvious in the colour choices that seem to hang together within a certain tonal range, and a kind of handwriting style that is evident when Read uses lettering. These elements combine to give the body of work its own textured particularity, deliberate idiosyncrasies that pull some of the more fragile and tentative moments to a point of concentration.

In this manner, Other Possibilities renders the suggestive condition of potentiality into a moment of clarity, into arrival. The territory of Read’s work is a wobbly, uncertain one that wears its failures and anxieties on its sleeve, yet it has also been articulated into a fully formed state of being. It is like a series of moments: the banal matter of everyday hassle, which can quickly get out of hand and become existentially terrifying, and then the moment of clarity that sometimes follows; the moment at which an idea becomes a form, has a shape, and can be spoken.