Exhibition Essays

Glover Park Project

May 2011

DREAMY CITY WITHOUT GREEN SPACES

Raewyn Martyn

When former Trade Union Secretary Lewis Glover passed away in 1964, he ensured his estate was handled in a manner consistent with his commitments and ideals. Glover left his false teeth to the Town Clerk, his bicycle to the chairman of the council’s transportation committee, and his money to the people of Wellington.1 The working man’s Glover bequeathed $24,0002 to the Wellington City Corporation for “a park to be established within the vicinity of the City to be used for recreation purposes”. Between 1964 and 1969, the Council acquired a series of parcels of land between Ghuznee and Garrett Streets, which would form the site for a place of rest and recreation within the central city

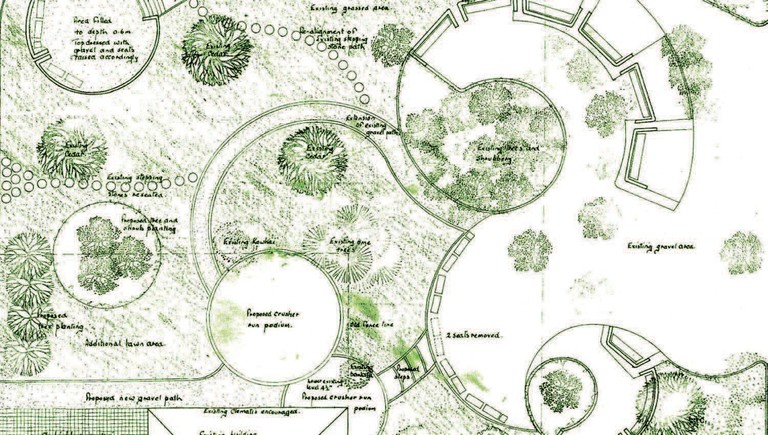

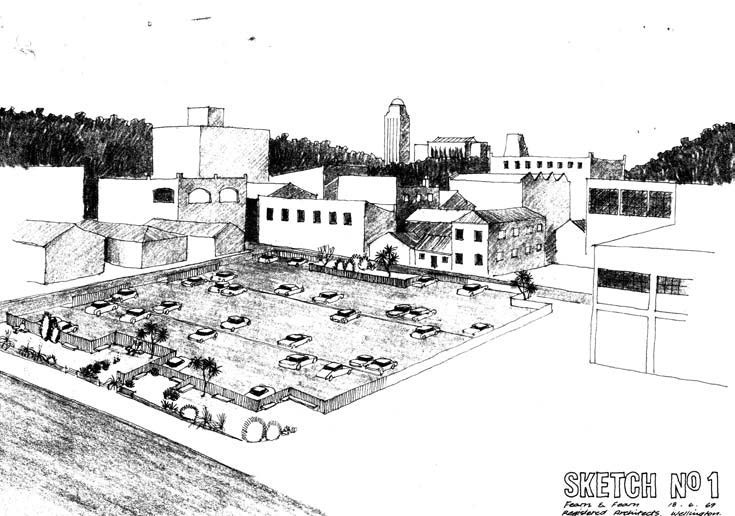

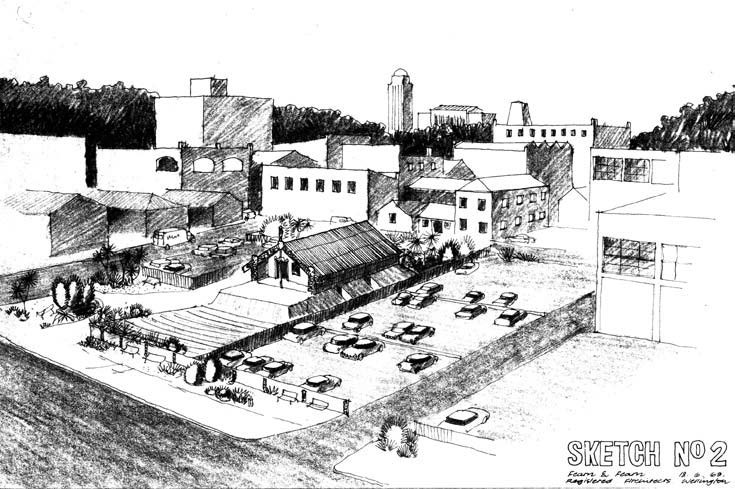

As time passed, Glover’s public intentions for the park came under increasing threat from private interests. After Cuba Street was converted into a pedestrian-only mall, the land was used as car-parking space for several years; in mid-1969, local businessmen lobbied the council to retain the carpark. They also protested plans to convert the land into a public park, and worried at the loss of such a “glorious commercial site”.3 Mr A. Cornish, a local Wellington entrepreneur, proposed the erection of a Māori Pa, which would serve as a “most attractive and interesting”4 tourist venture, with the potential for additional attractions such as a trout pool and a gas-heated geyser, and a playground and crèche which would “prove a boon to shopping mothers”. Other sketches depicted more limited proposals, including the ‘Maori pa’ combined with a carpark.

Worried that the capital was becoming a “concrete jungle”5, the Wellington Housewives’ Association supported the proposal for a public park, and approached the council on the precise terms of Mr Glover’s will. In one newspaper article covering the debate, the Wellington Play Centre expressed discontent with the lack of green spaces in the city area, claiming that Wellington appeared drab in comparison to Auckland and Christchurch. This article’s peculiar headline—“Dreamy City without Green Spaces”6—has an accidental resonance. Presumably intended to read “Dreary City”, the typographical mistake yields an unintended poetic result.

Energetic public discussion of the park’s future continued into 1970, but the general awareness of Glover’s intentions allowed the council to commit to the development of a recreational park at the Ghuznee Street site. Work finally began, and Glover Park was officially opened on Arbor Day, on August 4th 1971.

The dream soon garnered a dystopian edge, with the ‘wrong’ kind of recreation occurring in the park. In 1973, just a couple of years after the park opened, The Truth reported that Glover Park had become known as “Alky Park”, the location of “open-air ‘fun’” for the “drink-and-vomit boozers”7. The populous of the dreamy city included homeless people, and the park made a place to sleep. This mis-recreation continued throughout the following decades, with various attempts at redevelopment to dissuade the antisocial behavior. There were concerns that the public park had been “'privatised'” by the behavior of these undesirables.8 In somewhat Foucauldian fashion, the most recent redevelopment attempted to resolve the problems through making the occupants of the park more visible.

Even today when wandering through the CBD it can still be a struggle to find a public space that provides quiet recreation or rest for free. During the 2011 Enjoy summer residency I spent lunchtimes in Glover Park. And while seeking out spots for off-site works in the Cuba Street area, the park seemed like a space suited to an outdoor canvas work. I wanted to make a negotiated intervention into exterior architecture, and the underused furniture of the park made sense. During the residency I also completed a series of wall-works in the gallery. These works observed the ambient natural light of the gallery space. which was custom-built in 1900 with a wall of windows for its use as a photographic studio. The works also used other ‘found’ qualities and architectural formats from within the space, and they were painted through meditative, largely unplanned activity, with the open-studio allowing this process to be observed. The offsite works also researched during the residency were to extend this use of ambient source material and site-responsive painting.

The painted canvas day-beds stretched and fitted between the existing bench-seats on the southwest corner of Glover Park are an intervention into the current furniture of the place of rest envisioned by Lewis Glover (The canvases are painted partially en plein air). These particular benches were constructed as a temporary gap-filler, while plans were underway for a sculptural work to be sited in that area of the park. The sculpture never occurred, and the slightly uncomfortable benches remain, underused.

These day-bed paintings sit somewhere between public and private; between personal artistic activity and an exploration of its social value. I’m interested in how the visual medium of painting can employ the strategies of current relational practice whilst also recalling earlier 20th century avant-garde histories, and the efforts these movements made to blur the distinctions between art and life. Occurring during Glover's formative years, these earlier art movements draw parallels with his active involvement in New Zealand's union movement during the early-mid twentieth century.

It is interesting to consider whether Lewis Glover’s political and social beliefs are still relevant to working life in Wellington, and how artistic activities operate as part of these ideals, and as part of daily rest and recreation within the current cultural environment. Whilst Wellington in the early 21st century has a more diverse industrial base and job market than Lewis Glover’s Wellington, the no-cost leisure and recreation activities have remained very similar, based on the natural resources and green spaces available within the city.

Roughly thirty years after the creation of Glover Park, a university art school opened its doors in temporary premises a few blocks away from Ghuznee Street. At this point in its history the “Creative Capital” now produced and employed many creative professionals, apparently helping to make the dreary city dreamy. As US academic Richard Florida has written, this “creative class” has considerable economic potential, providing labour for the relatively lucrative creative and information industries. Can these “creatives” not only contribute to economic or commercial regeneration, but also apply innovation to social and political problems? Artist Martha Rosler notes that Florida’s preoccupations remain primarily private, and he appears to have little interest in the potential for the creative class to contribute to “human liberation”. Rosler argues that most observers of ‘creatives’ “concentrate on taste classes and lifestyle matters, and are evasive with respect to the creatives’ relation to social organisation and control.”9

The Glover Park day-beds seek to draw attention to a social space within Wellington’s CBD, while also celebrating the knowledge and gift that allowed the park space to be established. The day-beds intervene with the social space set aside from business and consumption, and allow people to lie in the hammocks. Happily, the day-beds risk misuse, and may change or be added to during their days of installation. They offer a passing observation, and the potential space for daydream.

-

1.

“No Nightingale, tui rules ok” City Voice , October 19, 1995.

-

2.

At the time the Park was established in 1971, interest collected had boosted the amount to nearly 32,000. An additional 19,000 was collected when the last beneficiary of the late Mr Glover died in 1978/79.

-

3.

“Cuba Street Men Attack Park Site”, The Evening Post, September 19, 1970.

-

4.

“Maori Pa And Geyser Proposed For Glover Park”, The Evening Post, June 23, 1969.

-

5.

“Will Capital Be A Concrete Jungle? Ask Housewives”, The Evening Post, June 16, 1969.

-

6.

“Dreamy City Without Green Spaces”, The Evening Post, October 13, 1969.

-

7.

‘Drunk – and “Disgusting”’, The Truth, February 20, 1973.

-

8.

“Glover Park ...#254”, Wellington Daily Photo Blog, February 8, 2008, quoting Mayor Kerry Prendergast http://blandforddailyphoto.blogspot.com/2008/02/gloverpark-254.html

-

9.

Martha Rosler, “Culture Class : Art, Creativity, Urbanism, Part II : Culture and its Discontents”, e-flux journal # 23, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/219