Exhibition Essays

A long line of worshippers

June 2020

A long line of worshippers

Robyn Maree Pickens

I come from a long line of worshippers of strong crazy women*

I have been holding you+

walking along the clouds that hover over the Neva^

and as each screaming teakettle arrives∞

—Eileen Myles 1

*who have been elided: uncover them

+I have not been held enough

^walking from job to job

∞bow down

Georgette Brown, And Holds Us At The Center While the Spiral Unwinds, 2020, acrylic paint, mediums and rope on canvas and Annie Mackenzie, Saved Message, 2020, fruit loaf and voicemail recording. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

We know we are always in conversation with others: whānau—including chosen whānau, friends, lovers and partners, peers, predecessors, more-than-human beings and the ideologies and infrastructures that constitute us. Our conversations and relationships with dominant world-shaping ideologies and infrastructures are necessarily different, contingent on who we are and how we are supported. In this context, I am in conversation with the curatorial frame, artists and artworks of Fire-lit kettle, an unruly hedge, cabbage trees, swoop of kererū, friends who visit bringing soup and Eileen Myles’ poetry. I’ve listened, and in response, am prompted to consider this exhibition’s thematic of creative energy in each artwork, but also to raise more broadly the ways in which the art world (if it is possible to speak so generally)—as a particular embodiment of wider cultural values—conditions differential access, visibility, validation, and support. When the screaming teakettle of creative energy arrives, can you tend it? Or is there a pressing familial obligation? A split-shift clash? How is your mental health? Have you spoken with anyone this week? There may not be enough nourishment (mental or physical wellbeing, interpersonal, financial and infrastructural support, TIME) to bow down in that instant or stay there in the heat for as long as it lasts. Fire-lit kettle encourages these questions and analysis. It makes me want to keep asking: who struggles to tend creative energy, and how do art world (and life) infrastructures interpellate and exacerbate such differential struggles? This exhibition tackles several key creative energy/infrastructural dynamics, including those of tangata whenua, diasporic, and LGBTQIA+ communities.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Toro, piko, 2020, copper wire, harakeke, natural dye, māta, plaster, found rocks, pink spiral shells, pupu shells, melted glass, aluminium, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

The breeze

of the world.

It opened

my jar.

It called

me home. 2

Home, place or whenua might involve reaching upward and outwards like the toro, a slender, open-branched tree—perhaps as an embodiment of memory and whakapapa, and stooping (piko) to collect stones and shells from significant locations. Ashleigh Taupaki’s sculptural installation Toro, piko (2020) incorporates found objects from her Ngāti Hako iwi with handmade kete and waka huia woven from chicken wire and copper wire respectively and plaster “tiles” reminiscent of mauri stones. Memory, the gathering of place in the form of natural objects, and recreating domestic and sacred taonga, together materialise important creative sources and trajectories in Toro, piko. Taupaki’s installation animates the vertical and horizontal axes of toro/piko: the waka huia hangs suspended from the ceiling, while the plaster works arranged on the gallery floor cause the visitor to stoop down. Each small sculpture is either an aggregation of objects or a dispersion, which variously embodies the fluctuation of memory, the push and pull of home, and the creative process itself. Most of the vessel-based works, such as the waka huia, facilitate the aggregation of collected taonga, such as stones and shells, while the plaster sculptures—some of which support smaller, raised pebble forms—are primarily “broken” or carefully scattered.

Ashleigh Taupaki, Toro, piko, 2020, copper wire, harakeke, natural dye, māta, plaster, found rocks, pink spiral shells, pupu shells, melted glass, aluminium, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

How high is your rent?

If art is the highest

and most honest form

of communication of

our times and the young

artist is no longer able

to move here 3

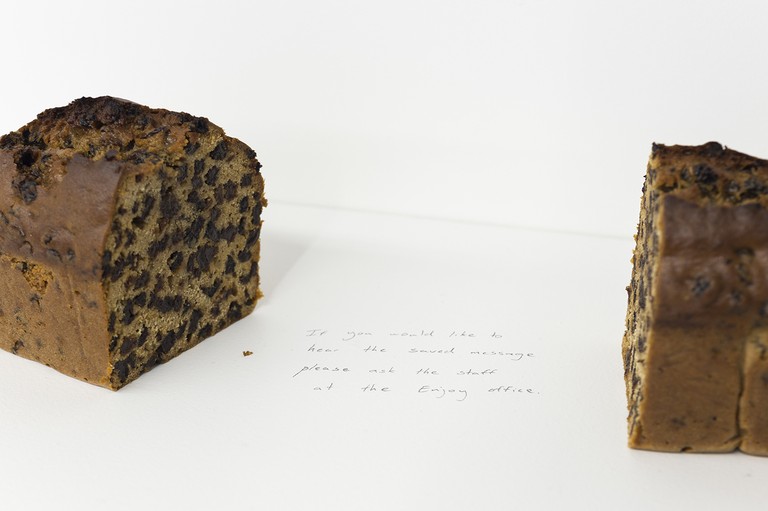

This excerpt is not a commentary on where Annie Mackenzie lives, and why, but it highlights one central theme of Saved Message (2020): intergenerational views on, and infrastructural opportunities for making a living from art (or craft). Mackenzie’s work—comprising a fruitloaf baked by the artist, a handwritten message advising access to a voice message, and the voice message itself: left by a family friend—situates these intergenerational differences in the context of whānau, manākitanga and the art/craft dynamic. The voice message provides the actual event, in which Rosie, a family friend, calls to apologise for her bluntness during a family visit, and makes reference to the “life of an artist” and the “bottom line.” However, the intersecting contexts of family, hospitality and intergenerational views on making a living as an artist are metaphorically captured by the fruitloaf cut in two halves. The fruitloaf is heavy; it stands in for the weighty conversation, while formally it manifests the two parties and viewpoints, the dialectical engagement, and two “listening cups” with the handwritten text written between the halves as the “string.” From this specific incident, Mackenzie’s work invites a broader discussion on how artists make a living, and the art world’s ambivalent attitude (or silence) on questions of class and transparency around privilege.

Annie Mackenzie, Saved Message, 2020, fruit loaf and voicemail recording, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

we must offer ourselves

up as food or eat

someone 4

Or eat cold soup from a can on cold rice while offering oneself up performatively, as Li-Ming Hu does in two video works Three Interviews (2019) and Acting/Not Acting (2019). The “Not” in the last title is a calculated misnomer, as both videos subject onscreen and off-screen life to the equivalence of compulsory performance and commodified labour involved, to various degrees, in art making practices. In both videos, Hu intersperses and overlays outtakes, behind the scenes moments and fictional scenarios with formal interviews for the School of the Art Institute (SAIC) Performance Department, Chicago and the Power Rangers RPM franchise. Although typically “off-screen” scenes such as eating soup, ironing a large green screen and installing and de-installing Hu’s convention booth are incorporated, they are clearly considered, scripted and performed inclusions that span an intentionally narrow affective range along the wry, abject, ennui-laden spectrum. By intermingling back stage and front stage, Hu’s work suggests that an artist’s performance of subjectivity in their work or, to extrapolate, in art world-related activities such as interviews and exhibition openings, can seep psychically into everyday life—especially undocumented, unfilmed life. In the context of Fire-lit kettle, Hu’s work provokes questions around the relationship between (especially) unconscious performativity of an artist’s off-screen subjectivity and creative energy: is everything performance (including downtime), and if so, what form does creative energy take?

Li-Ming Hu, Acting not acting, 2020, digital video, 04:32, installation view. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

are you

normal tonight? 5

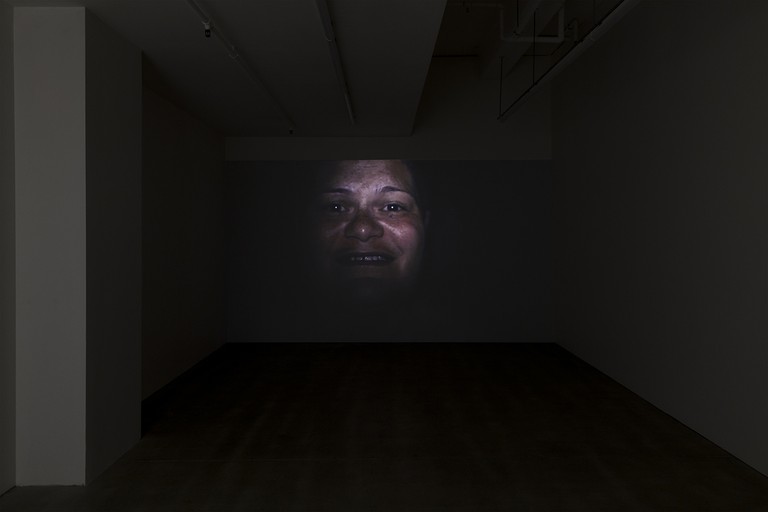

—in these night-like conditions when the weak light illuminates your face only slightly as you perform your version of Radiohead’s 1992 song Creep, and make it your own (Creep, 2014). Or more accurately, how is normality experienced if, like Fijian Anglo-Australian queer artist Salote Tawale, you grew up on unceded territory in Australia without seeing yourself represented in the media or pop culture? And how does invisibility impact on creative energy? One strategy Tawale employs is to indigenise and decolonise the archive—in this instance, the white, indie music scene. By re-performing and populating the archive with her presence, Tawale necessarily engages with performances of self and subjectivity. Emotional labour is involved. There is perhaps an affective response all too familiar for Tawale as she navigates and confronts the invisibility of certain diasporic communities. Tawale’s performance of Creep embodies this familiarity through the repetition of certain words, such as “creep,” as if the act of continually confronting diasporic belonging is quite literally a stuck record. Tawale critiques absence through iterative re-performance while simultaneously claiming space for herself and her various communities.

Salote Tawale, Creep, 2014, digital video, 03:11, installation view. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

her throat

an endless fall

onto a meadow of warm sushi 6

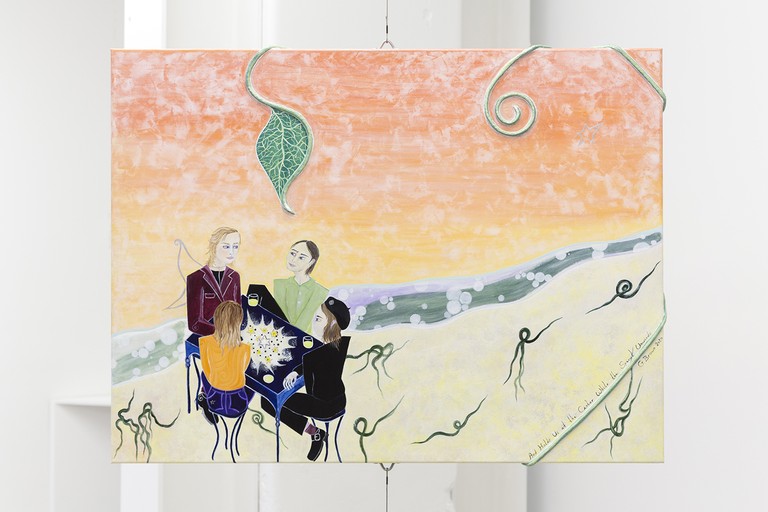

Georgette Brown’s suspended painting, And Holds Us At the Center While the Spiral Unwinds (2020) situates creative energy in the context of friendship and in terrestrial and marine ecosystems which human beings are part of, and depend. In this painting, te moana has disgorged an unexpectedly large meadow of seaweed on a shore. Despite the unpredictability of the ocean, Brown and her friends have brought a table down to the beach, which they sit around. The top of the table depicts an assembly of stars and black holes in an explosive burst, and a lone planet or sun beyond this galaxy. Brown and friends may be peering into the throat of a personal astrology, perhaps seeking a measure of certainty or, in reference to the title (and the painting’s installation), to “being held at the centre.” The painting, in terms of subject matter, title and installation manifests tension between stability and unravelling: a particularly socio-ecological unravelling of the biogeochemical systems and conditions that sustain life, as indicated by the ocean’s seaweed ejection, and the supersized leaf and vine that threaten to consume the scene. And Holds Us At the Center… can be interpreted as an opportunity to consider the ways in which artistic practice and creative energy are co-constituted by the more-than-human world.

Georgette Brown, And Holds Us At The Center While the Spiral Unwinds, 2020, acrylic paint, mediums and rope on canvas. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

I wrote something else

about the day holding me

and me holding you. A car

passes like a big breath.

It’s what I’ve got: all these

things and I hand them

to you like sex in the city.7

I hold you. I hand you this stencil. We are in this city together. Imogen Taylor and Sue Hillery’s collaborative work Sluice (2020) foregrounds creative energy and practice in the context of intimate relationships: specifically queer desire and partnership. What is it like to make art together as a queer couple? The dynamics of love, intimacy, desire and sex are immediately foregrounded. How do we discuss the work in this context? Check: boundaries. Check: interpretation. Check: projection. Start. Start with the work. A sluice is a mechanism for moving water using rotating blades within a cylinder. The large wall painting, Sluice, by Taylor and Hillery depicts a sluice in two-colour (green and orange) geometric lines on a pale purple background. This is not (only) a sluice. The framework of intimate partnership makes it almost impossible to avoid sexual connotations: this is an act of sexual penetration. Sluice is also a new iteration of Double Portrait: Screw Thread (2020), so there is a linguistic affirmation (screw) in play. On this reading, creative energy is fused with, and fed by sexual energy. But maybe there are challenges to sustaining shared creative energy? Here we return to the sluice, which can be deployed to defy gravity and push water uphill, embodying that challenge. Perhaps the challenges of queer creative partnerships are still exacerbated by heteronormative values? Frances Hodgkins’ painting Friends, Double Portrait (1922–25) of Jane Saunders and Hannah Ritchie would be more accurately titled, Lovers, Double Portrait. Sluice is a double portrait.

I’m writing that down

all that rattling heat in this room

I’m using that 8

Imogen Taylor and Sue Hillery, Sluice, 2020, acrylic paint, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

-

1.

Eileen Myles, I must be living twice (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2018), 205.

-

2.

Myles, I must be living twice, 171.

-

3.

Myles, I must be living twice, 137.

-

4.

Myles, I must be living twice, 194.

-

5.

Myles, I must be living twice, 138.

-

6.

Myles, I must be living twice, 148.

-

7.

Myles, I must be living twice, 322-323.

-

8.

Myles, I must be living twice, 6.