Exhibition Essays

Force-Morph

November 2011

Force-Morph: Exploring The Techno-Sublime in the Art of James Bowen

Henry Davidson

“Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt”

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

As the unmediated peril and awe of nature becomes further estranged from human experience, our understanding becomes more frequently negotiated through screens and visual technologies, the nature of the sublime moment has changed to such a degree that the most ambivalent, terrifying, inexplicable and truly sublime experiences we may have might now take place during a google image search or whilst lost in a youtube wormhole.1

Philosophical enquiry into the sublime has developed significantly in the last two centuries but the feelings traditionally characteristic of the concept are still present today and are increasingly evoked via image technologies. We might describe the trajectory of the sublime by saying that it has moved from recognition of the passion caused by nature, to that within one’s subjective self, and our experience of culture. The works within James Bowen’s 2011 exhibition Force-Morph rework the sublime experience in continuation of the Kantian notion of a “negative experience of limits... as a way of talking about what happens when we are faced with something we do not have the capacity to understand or control – something excessive.”2 Recent theories of the sublime claim that contemporary experience differs from Kantian knowledge. That there is no longer an attempt to re-assert the self in the face of the sublime but rather a wish to annihilate the self; I believe the techno-sublime is capable of critical, self-assertion through the appropriation and manipulation of images.

James Bowen presents a contemporary techno-sublime in Force-Morph, through his exploration of the contemporary gothic, a theme often associated with the horror and terror of subliminal experience; simulation as reality and the notion of super-hybridity.3 The thematic concerns of Force-Morph together create a techno-sublime; one that is rooted in hybridity, simulation and image anxiety but yet offer methods of resistance and reclamation.

Force-Morph is made up of three 700mm x 900mm digital photographic prints, a video mix tape projection and a cardboard box and LED installation. The works are arranged so that the projection faces the viewer when they first enter the space, with the prints on the left wall and the installation on the right side of the video. In the photographic print the user holds the power to re-form what was stolen from them four images float above a layer of fog or smoke in a void-like space, rotated and compressed, they appear to be lying, picture-side up. Smaller, repeated GIFs of the 80s B-grade gothic film character Elvira float down through the image reminiscent of snow flakes. The two top images show stills from 90s childhood movie The Adams Family Values and television show Eerie Indiana. The bottom two images depict teenage bedrooms, one adorned with an alien poster and the other a map of the solar system. This work embodies key concerns of the contemporary gothic through its spatial elements, abject qualities and the way in which it positions the past in dialogue with the present. In the user holds the power to re-form what was stolen from them we are presented with a dark, fathomless space. At the bottom, smog or smoke hovers, tinged reddish-brown, marking a horizon line where it meets with a deep black as it recedes into the distance. This ‘background’ to the rest of the pictorial elements generates a non-space that seems limitless. Catherine Spooner writes that “contemporary gothic is fascinated with spaces of absence: spaces where, even within apparently easy reach of civilization, one could disappear without a trace.”4 While the other components of the image make this space not-empty, their ghostly floating contributes to the feeling that this is an unknown and sinister frontier: “places without identity, spaces that are not places, these spaces respond to what in the over-populated Western world is one of the most disturbing (if all too-common) occurrences: disappearance.”5 The threat that the sublime poses is the possibility of this type of space-that-is-not-a-place, absorbing you and your individuality. In this sense, the gothic is always sublime because its obsession with and idolisation of death and death-like states (depression, darkness, disembodiment etc) are always present while repressed. The way the images within the picture space float with their face upwards in neat vertical rows is suggestive of clever storage solutions: of a repository of images. Perhaps this space demonstrates how the storage of digital images ‘looks’? Of how we might visualise the internet as an archive of pictures. In an age of intense simulation the endless reproducibility of images requires a host space, Bowen shows here; and in its immense-ness is truly sublime.

What also characterises this image-space as sublime is the gothic horror or abjectness of it. In the user holds the power to re-form what was stolen from them there is terror in both the complete surface of the image as well as in its infinite depth. The hovering film stills and the trickling Elviras unsettle with their superficial presence, while the deep space of the picture threatens to swallow us. The gothic in contemporary negotiates between opposites—surface and depth, horror and beauty. It is within this dialogical relationship that the gothic becomes sublime.

The floating images in the work draw connections to the gothic in their mediation on the past in the present. The movie and TV stills from the recent-past are haunting here; they demonstrate the inability of the gothic text to escape history. The Gothic is often characterised by a reunion with an unwanted or uncomfortable past. In this context, postmodern cultural production seems haunted by the detritus of what has been. Here, by B-grade mainstream cinema and counterfeit copies of gothic. Both The Adams Family Values and Elvira are highly constructed and camp gothic texts that play on stereotypes referring to their inherited yet often imagined gothic past for meaning.

The bottom two images of teen bedrooms refer to places where gothic imaginings might first take place—small, intimate personal spaces. Teen culture is rife with the gothic, Gilda Williams notes that its “inclination to transcend the ordinary, cultivate the anti-social and experiment with the sexual unknown makes Gothic a perfect haven for adolescence.”6 These teen spaces also allude to the places where online users re-appropriate images and invest new meanings in them. By taking content from file-sharing websites and using basic image manipulating programmes Bowen demonstrates how the teen bedroom also becomes the artist’s site of production.

In wow, gosh, oh gee Bowen further comments on the nature of simulation today. Layers of gaudy pink, purple and blue backdrops form borders and frame an image of two hands that are cradling or conjuring something. The use of and emphasis on ‘backgrounds’ through the works in this show is significant. These backdrops, in contrast to the vast wonder of a mountain or landscape are flat. Through their displacement of the perspective that an immense vista might provide for the individual, they create an alarming disorientation, a different type of experience of limits. In the top of the image a golden photocopier is repeated in an endless blur up and out of the picture. The two floating hands, reminiscent of ‘Thing,’ (a character from The Adams Family franchise), magically conjure up a hovering shopping basket of edible consumer goods—that looks as if it has been doused in petroleum jelly. Glittering scarab-like bugs also float in this strange sort of religious apparition. The gold of the photocopier elevates these appropriated simulations to the realm of fine art, signifying worth and value in ‘low’ user-generated images. Similarly the DIY aesthetic of cut and paste and photocopying is foregrounded as significant through showcasing the method of production within the image. The copy of the copy of the copy becomes celebrated. Simulation as sublime is shown through the central image of the hands, they appear to be conjuring or summoning in a mystical manner—the supernatural-ness of the scarab-beetles and the disembodied hands adds a gothic element of horror to the notion that the endless possibilities of simulation are sublime—the lack of limits and borders acknowledge the terror of technology, similar to how in both traditional and contemporary gothic (think Frankenstein as well as Blade Runner) the excess of and submission to technology charts the way to chaos and anarchy.

In the sanitized disguise appears before the disguised 21 white-boarded images are spread across a generic-looking desktop-like background. The images are varied but seem linked by their banal oddness. They might be the result of a google image search, where the desired picture cannot be found and instead one must make do with something not quite right. Not quite right in the sense that the image is a poor match to the idea one wishes to express but also that there is something not quite right going on. In one a large building burns in the centre of a tourist snap of a cityscape. In another a young bride looks forlornly at her aged husband. In yet another a familiar photo of the Loch Ness Monster has been altered so that a snail shell covers the creature’s head. This bizarre tableau of images further intensifies Bowen’s comment on the nature of hybridity by positioning the relationships between the images as, paradoxically, their difference.

While we may be able to draw connections between the images that the artist has selected for this work, the central similarity and the issue that Bowen draws our attention to is that above all the arrangement is super-hybrid, it is a mix of pilfered images that achieve connection in their disparity to one other—they are the same because they are all different. Super-hybridity references the postmodern techniques of bricolage and appropriation and as Jörg Heiser claims, explores the dynamics of globalisation, digital technology, the internet and capitalism. He describes how the super-hybrid process seems to be “about accelerating the amalgamation of sources and contexts to an extent that they are atomised and transformed into the seed of the next idea... the emphasis is less on a certain style, or look, than on a method.”7 But arguably super-hybridity does produce a certain look, and this is what Bowen explores in Force-Morph. Connecting these images, asides from their hybridity is a strong gothic theme. Like the graveyard or ruined castle setting of a traditional gothic text, the sanitized disguise appears before the disguised depicts the detritus of the internet image world. Poor images, those whose quality is inferior and content banal, are highlighted in the large format print. Each individual image is captioned with its JPEG title, further embedding the selection process in the realm of internet search engines which often produce peculiar matches to keyword or boolean search terms. By presenting such a tableau, Bowen draws attention to the ways in which the sheer quantity of images begins to level the difference between them but that also the need and desire for images underscores their content. It is in this element that there is truly something uncanny and terrifyingly sublime about the way we consume images in a postmodern world of simulacra.

Bowen presents just a small spread of images, a tiny link in the chain of image consumption, of an infinite loop. The repeated use of the Elvira motif through the photographic prints in the exhibition reinforces this idea of Sisyphean mythology. Like Sisyphus who was punished to forever push a boulder uphill only to watch it roll down and begin again, so are today’s viewers doomed to see their past constantly mined for capital, as the user holds the power to re-form what was stolen from them suggests with its juxtaposition of user-generator sites and mainstream cinema stills.

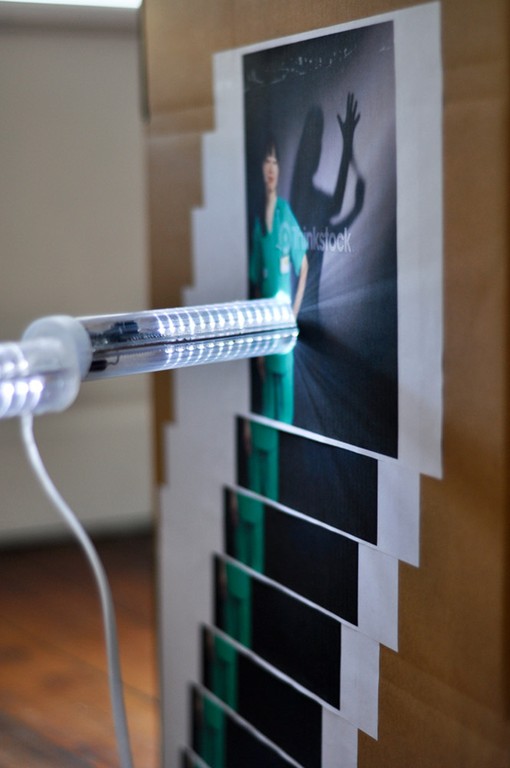

Accompanying the three prints is a cardboard box and LED installation on the floor. The piece consists of three semi-flattened cardboard boxes turned on their sides and arranged in a diagonal line. A tube runs through them containing LED lights which form a continuous line, or as the title of the work suggests, a procession of flickers. Taped to the side of each flattened box are six different Getty images.8 Each image has been constructed out of multiple copies layered closely to each other so that only the top image shows the picture in full. This layering has the effect reminiscent of both the LED procession as well as multiple windows open on a screen and the way in which they ‘ghost’ themselves when they are moved. Together, the images and the LED train are telling reminders of the way images are recycled and, via digital technologies, the way that images can make powerful and long journeys, both from the past as well as geographically.

Continuing the Elvira GIF theme, procession moves the idea of the infinite loop from the one-dimensional photographic surface to a more tangible sculptural form. The LED lights also reference neon signs in their endless recapitulation and perhaps the Las Vegas strip, the infamous site of simulacra and postmodern analysis. Like the sanitized disguise appears before the disguised the Getty images plastered to the cardboard structure have been lifted from the internet and are royalty-free stock editorial images; the kind that illustrate articles in magazines or provide a visual component to a column on ‘relationship advice’ or ‘technology’. The images that Bowen has selected are both banal and strange. In one a huge strawberry is on fire, another shows a sinister looking shadow creeping up on a female nurse, in another a middle-aged man wears a pageant sash that says ‘princess’. There is both a sense of unease and humour to their mass-produced, badly conceptualised nature. In the infinite loop of image production and utilisation, these Getty images symbolise the critical potential in the detritus of the spectacle as well as the redundant nature of images in the 21st century. The pictures are both ridiculous and dull. They are ripe for re-use, as Bowen demonstrates but they are equally disposable.

Combining the thematic material of Bowen’s large scale photographic prints and the LED installation is the video pray for your insignificant flesh, projected on to the wall of the gallery. It is a combination of screens, youtube memes, appropriated user-generated digital animation and low-fi computer graphics. This material is repeated, fragmented and tessellated, forming a visual mix tape of simulation. An accompanying soundtrack is likewise hybrid, including the likes of MIA, often celebrated for her wide use of sonic and cultural references. The mix tape brings together the motifs and conceptual elements in Force-Morph and its mediums: still images and sculpture combine in what might be the ultimate form of today: video. The mix tape begins with an exposition where a coloured rotating orb, similar to the Apple spinning wheel which signals one’s computer working too hard/on the brink of freezing, conjuring up a series of images that gradually speed up and lead into the main body of the video work. Aurally, this introduction is set to Acid Horse’s No Name, No Slogan, the title phrase which is chanted repeatedly through the song and flashed in the video in word art-like font, tinged in a Goosebumps green. In thinking about a contemporary sublime the phrase ‘no name, no slogan’ points to an ‘other’ or unexplainable thing—a product without a brand—a truly terrifying and unknown occurrence in the early 21st century.

The mix tape sits centrally in the show and can be seen as both an introduction or a conclusion. While the troubled characters of Edgar Allan Poe’s gothic fiction were ‘haunted’ in their various historical and imaginary settings, we might think of today’s haunting as addiction.9 pray for your insignificant flesh makes clear that our need to simulate reality through images results in a form of addiction, both to the past and the imagined future that is, undoubtedly sinister. In Force-Morph specters of the popular culture past haunt the gallery. The clip of Cher’s ten-minute blink directly embodies the Sisyphean mythology Bowen seems so obsessed with. Cher, a relic of the past, perfectly preserved (although in true Gothic fashion, there is definitely something wrong with her), performs this banal- turned-horrifying bodily function, slowed down and singled out. It appears at a turning point in the video. In tune with Bowen’s Force-Morph she is ultimate and pure simulacra.

Bowen’s mix tape is an ode to the culture and practice of ripping, to the super-hybrid. Amongst the plethora of material the artist features ‘super-cut’ youtube videos by the user- producer WendyVainity whose own work is focused on gothic themes. The WendyVanity rips include a skeleton dancing in a shroud and music video-like scenes of choreographed androids. WendyVanity creates her videos from various user-focused programmes, some of which are open platform. Bowen’s use of her work celebrates the creative potentiality of open source software. Also included is a repeated animation of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Children, which provides an art historical reference to the tradition of gothic, whilst cementing Bowen’s applaud for appropriation and simulation. The Goya clip appears, disturbingly, to resemble a pac-man game. The super-hybrid status of the mix tape is representative of a contemporary, techno-sublime because its mass of appropriated and simulated material engenders an overwhelming, limitless feeling and offers a kind of sensory black hole to the viewer. However the way in which it has been sculpted through Bowen’s editing harks back to how the lone figure in traditional sublime painting re-asserts the individual and reclaims the self in the face of annihilation. Force-Morph both celebrates and warns of mass, digital culture whilst it also exemplifies the nature of the techno-sublime as a user productive and radical tool for change. Through this body of work Bowen attempts to make visible the un-presentable and in doing so establishes a conversation about the nature of images today.

-

1.

A state of mind/action where one keeps linking to new videos in an endless quest for entertainment and visual satisfaction.

-

2.

Simon Morley. “The Contemporary Sublime.” In The Sublime. (2010) Ed. Simon Morley. Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press: London. p 16.

-

3.

A category of art discussed in a recent issue of Frieze, September (133), 96.

-

4.

Catherine Spooner. Contemporary Gothic. (2006) Reaktion Books: London. p 48.

-

5.

Ibid. p 49.

-

6.

Gilda Williams. “How Deep is Your Goth? Goth Art in the Contemporary.” In The Gothic. (2007) Ed. Gilda Williams. Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press: London. p 11.

-

7.

Jörg Heiser, Ronald Jones, Nina Power, Seth Price, Sukhdev Sandhu and Hito Steyerl. (2010, September). “Analyze This: Super-hybridity: what is it and should we be worried?” Frieze, September (133), 96.

-

8.

Getty Images, Inc. is a stock photo agency that supplies images to businesses and consumers. It targets three markets—creative professionals ( advertising and graphic design), the media (print and online publishing), and corporate (in-house design, marketing and communication departments). Getty has distribution offices around the world and capitalizes on the Internet and CD-ROM collections for distribution. As Getty has acquired other older photo agencies and archives, it has digitised their collections, enabling online distribution. Getty Images now operates a large commercial website which allows clients to search and browse for images, purchase usage rights and download images. (Getty Images, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getty_Images).

-

9.

Mark Edmundson. “Nightmare on Elm Street: Angels, Sadomasochism and the Culture of Gothic.” In The Gothic. (2007) Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press: London. p 29.