Exhibition Essays

They must still be around somewhere, those old things

February 2021

They must still be around somewhere, those old things

Paul G. Johnston

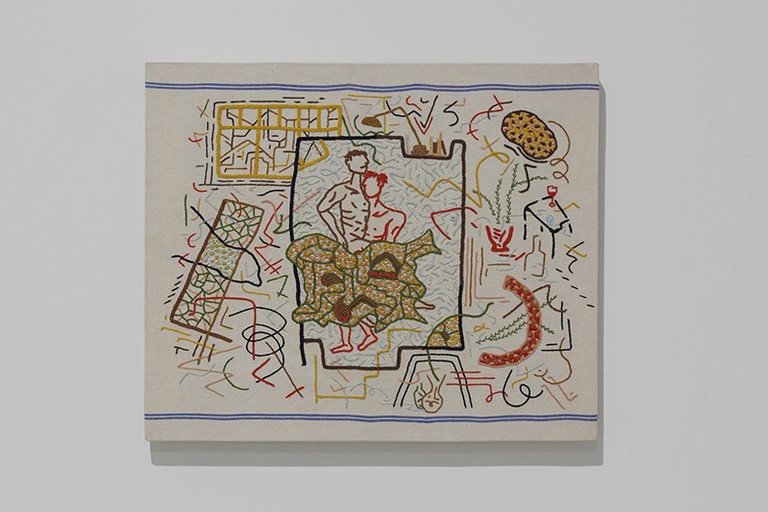

Areez Katki, History reserves but a few lines for you, 2021. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

It is three in the morning: I’m in bed, mostly asleep, but the light’s still on. I stir, and I open my eyes, briefly. Areez is at the desk, his back to me, crouched over a handkerchief, lost in his craft.

***

When he was a small child, about to leave the house in the morning, Areez Katki’s grandmother would pin a handkerchief, embroidered with his initials, onto his lapel. Today, vibrantly embroidered handkerchiefs form a core part of Katki’s artistic practice. In History reserves but a few lines for you, Katki offers five buoyant handkerchiefs, suspended from the ceiling on invisible threads. They share a common origin as hand-me-downs from his grandmother, their connection to her ritual of care made very material by their provenance.

A handkerchief can be so much more than just a handkerchief, as Herta Müller vividly showed in her 2009 Nobel Lecture. The opening:1

DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was the question my mother asked me every morning, standing by the gate to our house, before I went out onto the street. I didn’t have a handkerchief. And because I didn’t, I would go back inside and get one. I never had a handkerchief because I would always wait for her question. The handkerchief was proof that my mother was looking after me in the morning. For the rest of the day I was on my own. The question DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was an indirect display of affection.

For Müller, this simple gesture, and the humble object that it involved, becomes a symbol of stability, of safety in a Romania beset by the violence and uncertainty of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s totalitarian regime. As John Hamilton has written, Müller’s “reflections on handkerchiefs … demonstrate that this ordinary article can secure a sense of humanity in the midst of grossly inhuman and inhumane circumstances.”2 Katki’s life has not been lived under the dehumanising spectre of dictatorship, to be sure, but the quest for security is a universal one, and one made all the more challenging when navigating life as an immigrant in a new country and a queer person born into a tight-knit ethnoreligious community. Katki’s handkerchiefs are not so different from Müller’s. A handkerchief pinned to his uniform was one of those intimate gestures that made him feel safe, made him feel loved, made him feel at home even as he was about to walk out the door. Home is a handkerchief, so to speak.

History reserves but a few lines for you is fundamentally about this quest to find home, to feel home, to make home, in a world that doesn’t always make it easy, especially for a queer person. One of the artist’s primary references in creating the show’s five handkerchiefs was the poetry of the Vietnamese American writer Ocean Vuong, work that gives vivid voice to the liminal experience of inhabiting a queer body amidst the parallel strain of growing up in an immigrant family.3 Katki’s handkerchiefs can be viewed as synaesthetic responses to Vuong’s poetry, underscoring the transnational and cross-cultural solidarities of the queer migrant experience.

Areez Katki, Trojan, 2021, cotton thread hand embroidery on muslin handkerchief. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Trojan (2021) is my personal favourite of the exhibition’s handkerchiefs, a stunning, dense composition in warm reds and browns, featuring a horse rushing toward a fantastical array of skyscrapers. It takes its name from Vuong’s poem of the same name, an evocative piece, vividly colourful in its language, that invokes the sheer joy of a queer child stretching the boundaries of gender, alongside the ever-present threat of violence that attends his exploration. Yet it ends on an optimistic, defiant note:4

How easily a boy in a dress

the red of shut eyes

vanishes

beneath the sound of his own

galloping. How a horse will run until it breaks

into weather—into wind. How like

the wind, they will see him. They will see him

clearest

when the city burns.

It is this closing image that Katki brings to life on his handkerchief: the moment where the threat of the outside world disappears, and the queer subject re-emerges at its fullest extent. Not only that, but this transcendent moment also holds the promise of a rupture-causing visibility. Both poem and handkerchief, of course, engage with the long history of the Trojan War as a motif in European literature and art, albeit in a way that seems to threaten that tradition and the values it has been used to represent. Vuong and Katki are Trojan horses, queer immigrants to the western world, working from the inside to put alight its entrenched structures of racist heteropatriarchy. They will emerge from the horse—they will be seen—and the Troy that is this homophobic world will go up in flames. Troy is burning, Paris is burning: this is nothing to lament.

Perhaps the most emblematic work in History reserves but a few lines for you is Threshold (2021), a tiny, subtle intervention in the gallery space that you could quite easily overlook. The artist has filled a jagged crack in the concrete floor marking the entrance to the gallery with delicate glass beads in a pale pastel colour palette. The beads, dangerously loose, dangerously fragile, dangerously underfoot, find an uncertain home in the concrete, quietly existing in a context where they’re not quite welcome. Soft and brittle against solid and sharp.

Areez Katki, Threshold, 2021, Czech glass beads. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

There’s more. These beads are not just any beads: just as the handkerchiefs came from his grandmother, these beads were inherited from the artist’s great-grandmother, encoded with a history that is both deeply personal and culturally symbolic. They are beads of a kind used by his matrilineal ancestors to weave tōrans, decorative valences that mark thresholds. They are beads, then, that evoke a culturally specific history of making home through handicraft. With Threshold, Katki metonymically performs a way to exist authentically in a globalised world, upholding yet transforming his ancestral heritage. The traditional beads remain but Katki, transplanted from Mumbai to Aotearoa, reinterprets and reuses them in an entirely new context, pointing to the complex identity shifts wrought by European imperialism and the migrant experience.

Another wrinkle. The beads themselves are paradoxically an artefact of the British occupation of India, imported from that part of Europe we now call Czechia, reflecting the unpredictable transcultural dynamics of imperialism. Dimensions of the imperial culture become adopted, adapted, naturalised by colonised subjects, who retain agency in a complex exchange that cannot be reduced to a simplistic model of imposition (compare, too, Vuong and Katki’s subversive reimaginings of the western ur-motif of the Trojan War).5 The beads are also now an artefact of the past, no longer in production; this quality they share with handkerchiefs, a fabric form now rendered outmoded by the mass production of paper tissues. Katki animates these obsolete items, activating the highly personal histories that they embody and deploying them in a way that speaks vividly to the present.

The reinterpretation and reinvigoration of tradition and history from a queer postcolonial standpoint is central to this show, and Katki’s practice more generally. The exhibition’s title makes this clear. History reserves but a few lines for you: the artist offers us a few more lines from his unique perspective. This title comes from a translation of “Kaisarion,” by the Alexandrian Greek poet C. P. Cavafy. The poem’s speaker describes opening a “volume of inscriptions about the Ptolemies,” the Greco-Macedonian kings of Egypt between the late fourth and first centuries B.C.E., where he seems singularly unimpressed by the repetitive “praise and flattery” levelled at these rulers. But he notices something amidst all this insincere vainglory:6

I would have put the book away had not a brief

insignificant mention of King Kaisarion

suddenly caught my eye...

And there you were with your indefinable charm.

Because we know

so little about you from history,

I could fashion you more freely in my mind.

I made you good-looking and sensitive.

My art gives your face

a dreamy, an appealing beauty.

“Because we know so little about you from history,” is how Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard render the Greek lines that, in David Connolly’s more resonant translation, provide the exhibition’s title.7 This is a vivid illustration of the creative potential that exists in the gap of translation, where a new text emerges from the interpretive act of linguistic transfer. Similarly, in Cavafy’s poem the historical lacuna surrounding Kaisarion affords the speaker with an opportunity, a moment of translational creativity that allows him to invent a version of this figure for himself. He crafts a version of Kaisarion that resonates with Cavafy’s delicately homoerotic vision of the world. The poet looks into the past, and in the mysterious figure of Kaisarion finds, or rather makes, a queer icon.

When Egypt was conquered by Octavian (later Augustus, the first Roman emperor), Kaisarion, the biological son of Octavian’s adoptive father Julius Caesar with Cleopatra, was rendered a potential threat to his power. As Cavafy reminds us at the end of the poem, “Too many Caesars” presented a problem, so young Kaisarion was put to death. But the ancient biographer Plutarch hints at an ultimately unrealised alternative: Cleopatra’s plan to ensure her son’s escape from these violent circumstances by sending him to India, far out of the reach of Roman power.8 It may have failed, but this maternal act of love hopefully suggests the possibility of undermining the values of a patriarchal world, of creating a new home that denies the violent impulses of empire.

Kaisarion’s planned eastward exile in the face of a hostile invading force also resonates closely with Katki’s own ancestral history as a Parsi, a member of a small diasporic community who settled in Gujarat, India beginning in the seventh century C.E. in the aftermath of the Muslim conquest of Persia, forced from their homeland because of persecution for their practice of the region’s traditional religion of Zoroastrianism. Cavafy’s Kaisarion stands in an ambiguous relationship to Katki, a malleable historical figure who resonates on the one hand with the artist’s modern-day queer identity and advocacy for maternal knowledges, and on the other, in a fragmented way, with the ancestral exile that remains central to the identity of the ethnoreligious group to which he belongs.

Cavafy’s queer poetics bring to light a homoerotic world in an early-twentieth-century Arab city that would otherwise lay hidden and lost to history. There is a transcendent beauty to the queer experience in Cavafy, which in part extends from its veiled, temporary and secretive contexts. But occasionally, the poet strikes a hopeful note:9

Later, in a more perfect society,

someone else made just like me

is certain to appear and act freely.

In Katki’s work, that “someone else” feels proximate; perhaps it’s even himself. History reserves but a few lines for you imagines a way for the queer subject to make home, to actively construct the “more perfect society” that Cavafy could only wistfully imagine. In Small Places (Farrokh & Sohrab) (2018) is the most direct statement that Katki provides of what this society might look like. Inspired by David Hockney’s Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy (1966), a series of etchings that show male figures sharing intimate moments and spaces, the work shows two nude men entwined under a blanket in a visibly domestic setting. Unlike the floating handkerchiefs, this panel is stretched onto a frame, ordered and stable. A vision of peaceful domesticity made queer, in sharp contrast to the sketchy impermanence of the affairs recounted by Cavafy.

Areez Katki, In Small Places (Farrokh & Sohrab), 2018, cotton thread hand embroidery on hand-loomed tea towel. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown

The subtitle of Katki’s work points to the culturally specific way he reimagines Hockney and Cavafy. Sohrab is a hero from the tenth century C.E. Persian epic the Shahnemeh of Ferdowsi, who was mistakenly killed by his own father; Farrokh is Farrokh Bulsara, stage name Freddie Mercury, undoubtedly the single most famous Parsi of the twentieth century, and one who was famously queer but struggled to reconcile that fact with the expectations and values of his family and cultural background. The bold transhistorical linkage between these figures seems to suggest the unconventional, intergenerational and cross-cultural strategies of affiliation that help queer people make their place in a world where the heteropatriarchal logic of reproduction often fails to make space for their experiences.

Yet it also suggests the possibility of openly honouring traditional culture as a queer individual in ways that were sometimes unavailable to previous generations, where living as queer often necessarily entailed renouncing heritage. Freddie Mercury’s famous moustache has typically been understood as part of his embodiment of the “Castro clone” gay archetype of the 1980s, an index of queer culture’s tendency toward homogenisation. But Katki’s work points to a dormant alternative mode of interpretation: we might, simultaneously and not mutually exclusively, understand it as a reflection of a distinctly Persian taste for moustaches which long predates the rise of this kind of facial hair as a gay signifier beginning in 1970s San Francisco. The few lines of history that are reserved for Mercury have a tendency to forget the singer’s position as a Persian, born in Zanzibar and raised in Mumbai, perhaps because he himself downplayed his heritage in a misplaced hope for assimilation. Katki’s artistic practice, by contrast, promotes strategies of queerness that do not deny but rather affirm the other overlapping identities that we carry with us in the postcolonial world of the twenty-first century.

Katki’s work opens up a lively dialogue with the sophisticated and influential analysis of the cultural dynamics of our contemporary world developed by the postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha—himself, not incidentally, a Parsi like Katki and Mercury. Bhabha talks of culture as something that happens, so to speak, in the “beyond,” invoking the liminal space of the staircase as an image for how culture and identity is produced, through constant interaction between groups and individuals, unstable and in constant flux.10 He emphasises the condition of “unhomeliness,” a displacement in which “the borders between home and world become confused; and, uncannily, the private and public become part of each other, forcing upon us a vision that is as divided as it is disorienting.”11 It is the fate of the postcolonial subject to wrestle with this unhomeliness, to deal with the constant encroachment of the world outside on private lives, the unwillingness of imperial and neoimperial power structures to let the private exist free from the violence of the public sphere. But it is in the navigation of this unhomely, liminal, threshold condition that art helps not only make sense of the world but also make changes in it, by reinterpreting the past and disrupting the present, creating a “sense of the new as an insurgent act of cultural translation”.12 Bhabha gets at Katki’s translational use of the past, of histories, to forge a way of being that is authentic and grounded, and yet novel: to claim a home amidst unhomely conditions.

For me, the best single word to describe History reserves but a few lines for you is, precisely, and somewhat paradoxically, homely. The back room of Enjoy—a white box gallery, sterile white walls, stark concrete floors, no windows in sight—is rendered, somehow, warm and inviting. In part it is the dim, comforting lighting design: step over Threshold and you enter a space lit like a bedroom late in the evening. But it is the embroidered fabric interventions that make the space feel inviting and almost plush: the floating handkerchiefs, In Small Places hanging on the back wall, and most importantly, the two large-scale pieces that dominate the space. These two, both older works substantially recontextualised for this exhibition, by their scale and by their recognisable materiality do the real work of space-making in the gallery.

Areez Katki, Dwelling, 2017, cotton thread hand embroidery on upholstered silk textile. Image clurtesy of Cheska Brown.

Dwelling (2017) takes the form of a divan. This word is etymologically Persian in origin and possesses an evocative and remarkable additional meaning: as well as a daybed, a divan can be a book of poetry. This linguistic association might be taken as a resonant image for the way Katki’s physical artworks are regularly implicated in the artist’s prolific reading and writing, and the complex and ambiguous meanings that his work draws out of both interactions and discontinuities between page and materiality. While Dwelling was originally created as a mediation on the fictional Marabar Caves and the sexual violence that takes place there in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, here the work takes on a wholly new identity.

R. Radhakrishnan suggests that Forster’s novel explores whether it is possible to “invoke an equal and reciprocal politics of human recognition during times when the human has been betrayed by the binary machinery of colonialism.”13 Katki, now, insists that the answer is—must be—yes. Dwelling has become an assertion of humanity: it is here rendered an inviting object that speaks of a quest for comfort and safety, in a powerful testament to the transformative potential of time and context. While it was formed out of Forster, the artwork now has its own independent existence, and, resting on the floor, it evokes in three-dimensional reality the domestic space imagined in In Small Places. It is this object, above all, that makes the room homely, that transforms the exhibition as a whole into an experiential imagining of a queer home.

Areez Katki, Drapery, 2019, cotton and silk thread embroidery on 80% linen/20% cellulose textile, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

But Drapery (2019) is the show-stopper: a curtain too tall for the room that it is in, trailing onto the ground. Drapery is a second threshold, one that is grand, large and soft, one that lends a tangible sense of intimacy and privacy. It is embroidered all over with male nudes—mostly self-portraits—that suggest a certain vulnerability but also offer up the potential for voyeurism. Drapery makes ambiguous the relationship between the private and public sphere, blurring the line in an almost disconcerting way. Indeed, like Dwelling, in a different context it might easily be a distinctly unhomely object, in Bhabha’s sense: like its original outing in Come, remember (2019) at the University of Auckland’s Window Gallery, in which the curtain partially concealed elusive nude photographs of Katki taken by Ophelia King.

But here, in dialogue with the other selections in History reserves but a few lines for you, it seems, more simply, more humbly, to invoke nudity as an index of privacy and intimacy. The unhomely is domesticated; what was once, almost exhibitionistically, on public view behind a window in the entrance to a busy university library is now contained in a quiet, small place. The artist asserts his capability to forge himself a home in a hostile world, to make for himself, on his own terms, the security of a truly private, truly intimate life.

***

One of my very first memories of Areez: I’m sitting in his bedroom, watching him embroider the large curtain that would become Drapery. I’m not quite at ease; something of an intruder in someone else’s domestic space.

I still watch him embroider. I don’t feel like an intruder anymore.

-

1.

Herta Müller, “Every word knows something of a vicious circle,” Nobel Lecture 2009, translated by Philip Boehm, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2009/muller/25729-herta-muller-nobel-lecture-2009/.

-

2.

John T. Hamilton, Security: Politics, Humanity, and the Philology of Care (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), 32.

-

3.

Above all, those gathered in Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2016).

-

4.

Vuong, “Trojan,” in Night Sky, 9.

-

5.

See, e.g., Silvia Spitta, Between Two Waters: Narratives of Transculturation in Latin America (Houston, TX: Rice University Press, 1995), 1–28, on the cultural dynamics of the encounter between colonised subjects and the imperial power in the context of Latin America.

-

6.

C. P. Cavafy, “Kaisarion,” in Collected Poems, revised edition, trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, ed. George Savvidis (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), https://www.onassis.org/initiatives/cavafy-archive/the-canon/kaisarion.

-

7.

C. P. Cavafy, “Caesarion,” Selected Poems, trans. David Connolly (Athens: Aiora Press, 2013), 49.

-

8.

Plutarch, Life of Antony 81.2.

-

9.

Cavafy, “Hidden Things,” in Collected Poems, https://www.onassis.org/initiatives/cavafy-archive/hidden/hidden.

-

10.

Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 5–6.

-

11.

Bhabha, Location of Culture, 13. “Unhomely” is, incidentally, a refraction of Sigmund Freud’s unheimlich, a word more usually and more literally translated “uncanny.” Instead of translating the word as a whole, Bhabha’s version parallels the agglutinative structure of the German word, un-heim-lich becomes un-home-ly, drawing attention to the centrality in the original word of the home/Heim as a powerful image of the familiarity which uncanniness throws into question.

-

12.

Bhabha, Location of Culture, 10.

-

13.

R. Radhakrishnan, “Why Compare?” in Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, ed. Rita Felski and Susan Stanford Friedman (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 26.