Exhibition Essays

Aquarius, Pisces, Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn

April 2011

Horoscopes: Selected at Random?

Matthew Crookes

There is a certain logic in hosting an exhibition whose participants are selected on the basis of their birth date. There is equally an astute insight in bringing together astrology and contemporary artists, although the most interesting interface may not be the most obvious. What the popularity of horoscopes illustrates is a need for the irrational, or at least an alternative logic. A sort of counterbalance to a world which still owes much of its outlook to eighteenth century rationalism; a world which makes few allowances for metaphysical speculation. Horoscopes form a small part of that whole gamut of activity which includes religion, an interest in the supernatural, right through to gambling and belief in luck and fate.

There are, on closer examination, a great many areas in our lives where the same play on doubts operates—as well as a desire to give things over to chance, or to appeal to some agency other than the rationalism of a material world for guidance and assurance. It does not take long to appreciate the way our insecurities can become the basis for so many activities and secondary industries. We have a desire to make connections and narratives in those things which seem not to make sense and are disconnected. Whether it be the stock exchange, the advertising industry, Your Stars Today, or the newspaper article proclaiming a link between fish oil capsules and better exam results, we are continually reminded of the nagging fear that what we experience as the world is an incomplete and unsatisfactory fiction.

Western Astrology, the premise on which Zodiacal horoscopes are based, originated with the Babylonians. Furthermore, divination has provided the basis for which major political decisions and shifts in power were made—the Romans made no important decisions without consulting their auguries. The common expression “under the auspices of...”, derives from their observance of birds’ flights in divination. In more recent times controversy erupted over Nancy Reagan’s relationship with astrologer Joan Quigley, whose influence in her husband’s political career is still debated. Winston Churchill’s war cabinet considered banning newspaper horoscopes, viewing them as a potential threat to public morale. While newspaper editors dismissed horoscopes as superstitious nonsense, astrology remains a multi-million dollar industry, it’s spin-offs including books and phone lines.

It plays on a similar emotion that gambling also taps into—a momentary escape, a surrender. A fleeting moment as we let out the clutch and disengage between gears—coasting along and leaving everything to fate. But just for that duration. Winning money on a horse is an utterly different emotion from earning interest on savings, although in fact neither one is any more pre-ordained than the other. Banks manage risks on a grander scale and thus give an appearance of security. But like organised religion, banks have also outgrown the acts of faith originally placed in them. Since most people no longer look to organised religion for spiritual guidance, they invest their faith elsewhere—be it a return to the supernatural, or a search for the metaphysical. From another perspective, we might regard horoscopes as an opportunity to address the absurd, meaning the disparity between what we experience in our physical world and what we suspect might be out there in the metaphysical. In other words, it is an underlying search for a connection with the irrational, a desire to predict the unpredictable, while simultaneously reveling in the unreliability of it all. Astrology, for all its popular appeal, remains in the tray marked “rejected knowledge” along with other knowledge forms such as water divining, witchcraft (white and black) and alchemy.

In consideration against this background, is foretelling the future really what this exhibition is about? Of course not. But, it does use as a starting point an act of faith, however initially frivolous. Within the show’s own rationale, two broad responses are evident—that of responding in a personal way to one’s own star sign, or else responding to the notion of horoscopes generally. As a topic to address in an art work, the Zodiac makes perfect sense for an artist. As an example of the latter, Sonya Lacey’s works, consisting of spray painted images (lifted from the Trade Me auction site), purportedly suitable for a catalogue although simultaneously pedestrian in their blandness. The images, being sprayed particles onto a surface, are ultimately “dust”, and in a sentiment reminiscent of Albert Camus, she describes how spirituality might play out, or become apparent, in the choices we make within consumer culture, or indeed the randomised choices we encounter on sites like Trade Me. In contrast Tessa Laird’s work is an example of a more literal (and literary) interpretation of her own star sign. Here the issue is very much of the world, and in particular of the (apparently) unreconciled schism between the disciplines of Fine Art and of writing—at least within those sections of the Art community which Laird engages with. In its presentation as a kind of schizophrenia, her work could be viewed as much as a protest about an entrenched narrowness of vision, a political cry of angst, using the split within Gemini as a convenient metaphor.

We can contemplate the conversation between the objects in the room, brought together we now know, through a sequence of events which may have been pre-ordained, or may have been random. Since all exhibitions involving living artists have an unpredictable component, something which remains unresolved up until, and sometimes after, the show opens to the public, we have to ask ourselves just how controlled an event any exhibition can be, however finely-tuned.

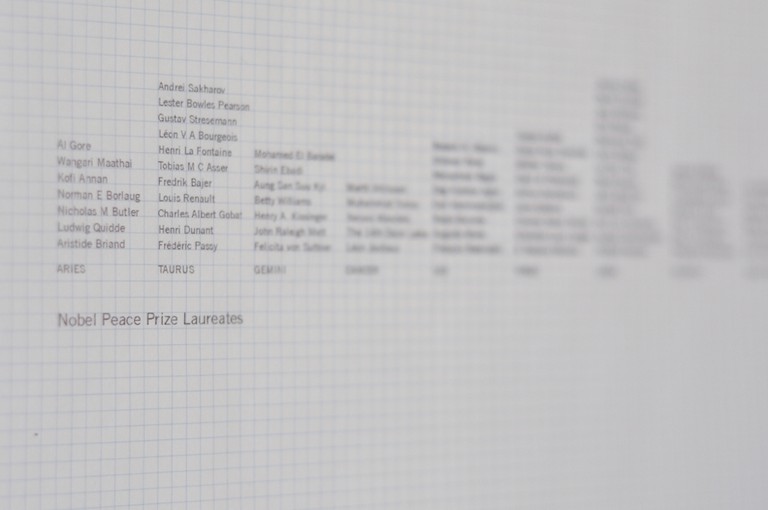

The kind of broad-brush descriptions evident in popular astrology exist in art writing as well of course, although there is usually something tangible in the room or on the screen. A more revealing look at the generic quality of popular horoscopes and the non-committal nature of their advice echoes the way the ‘future’ is updated throughout long-term weather forecasts; the adjustments, the constant revisions reminiscent of a market of fluctuating futures in which nothing is bought or sold and what is at stake is the credibility of the industry making these predictions. This trait is perhaps most clearly evident in Fiona Jack’s lists of eminent or notorious persons grouped together by star sign. In keeping with her investigations into taxonomy, groupings and statistics, it shows up, with a certain dry wit, the fallacies surrounding results drawn from such data. Throughout the same popular press that carries the most high profile horoscopes, medical data or other statistics are presented out of context, and from them false conclusions and correlations are drawn. Ironically these are then presented as “hard facts”, to which the horoscope is an antidote, or even a “pause for reflection”.

What can an artist do in such a treacherous and arbitrary environment? Faced with a universe which gives out so many false leads and conflicting signals, what more can we do than to pick those elements that appeal the most. The astrologer calls for a leap of faith. Objectively this is no more preposterous than all the other articles of faith we hold to in our lives. We are as innately objective as we are logical, which is to say not at all. We might do well to look upon this gathering of works as a diversity of coping strategies.