Exhibition Essays

A History of Space is the History of Wars

September 2007

In-between

Jaenine Parkinson

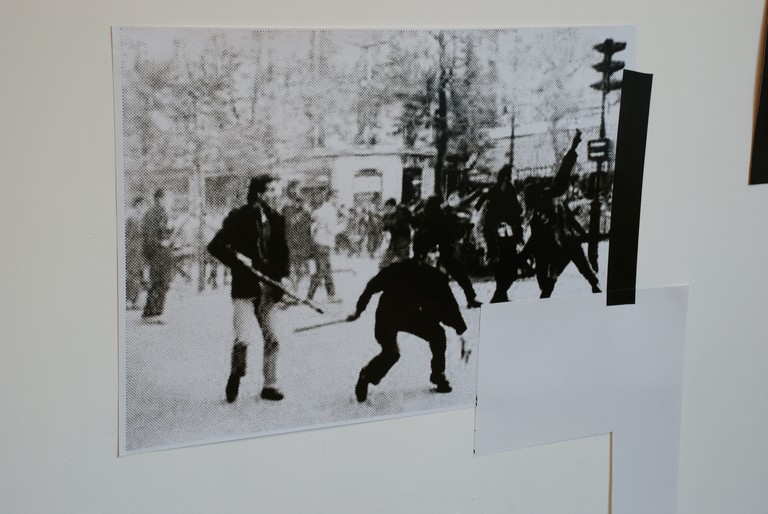

On first appearances it seems that the components of this show are at odds with each other. Delicately washed, abstract, grey-scale watercolours of faceted architectural forms converse with photographs and nameless newspaper clippings of street riots and demonstrations secured to the wall with duct tape. There is an almost unsolvsble opposition between the meticulously executed watercolours and the rough-cut Xeroxed newspaper dippings. Consequently, this show could easily be read as an exhibition of discrete works to be considered independently, but it seems to hold more potential when read as a unified installation. I tend towards this interpretation, in a search for a meanings and connections in the space between the watercolours and photocopies. It is this interstice that invites me to linger, poised at the juncture between the images, contemplating their connections and divergences.

Visually there is a unifying monochromatic schema to the whole installation. There is a conflict of black and white; dark and bright; presence and absence; past and present; but then there are the fissures, the layers of ambiguity; the bits that fall inside and outside, the shadows. It is not the oppositions of black and white that interest; it is the countless shades of grey in between. Those are the moments when the black surfuces of the masking tape turn shining white in the right light; the loosely hung layers of white paper trace dark outlines onto the wall; the maze of tonal shifts in the countless layers of watercolour washes.

More though than the colour-coordinated monochromatic duct tape, it is the title of this exhibition, A History of Space is the History of Wars that holds all the pieces of the show together. The title evokes the way history and place are enmeshed in experience; the way territories are demarcated and challenged, where abstract notions of borders are contested and the way history is construed as series of progressive stages propelled forward by conflict. These notions of history, territory, time and space - all constructed by-products of social relations and conventions - surface as the subjects of the installation when considering the relationships between the component parts. In Mestroms work there is a possible suggestion that the notions of space and history themselves have shattered upon examination, no longer stable, coherent or homogenous. Presented here are fragments of time and space - scraps of paper, off-cuts of history, snip pets of space, shards of time. The newspaper cuttings are both remnants of a lived experience and abstract siguifiers that stand as place-holders for ideas of historical struggle and our shared mediated perception of events. The watercolours are like delicate layers of memory that disintegrate into a thousand tiny pieces the closer they to come to being recalled.

We can perceive in Mestrom's shattered spaces different time durations comprised not of stable advanc ing and evenly spaced units, but of fluctuating dimensions and singnlar moments of differing intensity and consistency.Here the conventional abstraction of time and space as measurable and quantifiable, in seconds and millimetres, is only one possible understanding of duration and expanse. In order to have a stable concept of time and space there must also be a stable vsntage point to begin measuring from.

Is it a fractured subject that views this space and time -looking through different eyes, shattered eyes, nauseous eyes.compound eyes, digital eyes?

The abstract watercolours are computer-aided drawings translated by the familiar technology of the hand coupled with a pencil andbrush, and as such mix: and muddy the new/old divide between technologies. However, at first, it takes a few passes to discem which role each technique has taken in creating the abstract, layered, maze-like structures. An ever-so-slight pooling of watercolour pigment on the lower lip of the paper discloses the painting's handmade construction, which seems astonishingly machine-like in execution. The computer's products are transformed laboriously into exquisitely handcrafted patchworks of ink, to produce a geometric abstraction that seems as natural as the facets inside a sugar crystal. For Mestrom the virtual spaces created bythe computer act as a tool for abstracting, twisting, layering and fracturing space. All technology has this potential for opening up new connections and intersections -rupturing new ways of perceiving, but can just as easily shut down engagement with the world into habitual modes.

Mestrom's use of digital technology as a starting point for her watercolours opens up new processes, ways of looking and thought patterns, in strong contrast against the samples of the banal use of technologies for mass communication. History through mass media becomes not what is seen but more what is all.owed to be made visible. Not what is seen but what cm be seen. Inevitably, some things are illuminated, othen cast into the shadow. For the contemporary moment, Beatriz Colominia notes, "despite, orperhaps because of; the radical doubt of what constitutes an image of contemporary w:u,certain images are pushed forward to cover the huge gap in perception.1The media images Mestrom has selected here have come to signify one perception of street-level cultural revolution. Located historically, these images not only act as indexical reference points for the moments they capture, but also speak of what is omitted, what is left out of the frame and what is absent.

The repetition and duplication of images and forms is a strong method used in Mestrom's installation. The watercolours are all versions of the same architectural model rotated, filpped and pivoted. The media images are copies of newspaper prints -themselves duplicates. What is the result and intention of this repetition? Does it cause the work to become ingrained in the unconscious, or loose its affect; drained of significance? Does it reveal a pattern, or form a simulacrum -a sign torn from its signified? Or does it cause the work to be trapped in an eternal return, forever lacing the lived past with the actual present, to appear again in the future? Does it open up the possibility that exists with repetition for unintentional slippage and variation? These images could be seen as exemplars of Deleuze's concept of the crystal-image. This is a layeringand a fusion of the virtual memory of that which has gone before, and that which is possible to appear again with the actual nuances, physicality and particularities of the present moment in the way history, digital technology and a physical presence are laced together.2

There is a sublime feeling in the infinitely expanding and echoing macrocosmic or microcosmic spaces of watercolours. They produce a beautiful vertigo sending the viewer swirling around the architectonic space of the picture plane. This viewpoint can momentarily flick, to send you crawling across the flat grey lozenges of pooled pigment laid out across the surfuce. Perception shudders between seeing surfuce and depth, where complete abstraction can give way to realism produced in the optical illusion of pictorial space.The concept of the sublime can also be evoked when reflecting on feelings of individual inconse quence to the events of world history, which we are distanced from further when we perceive them trans posed and digested by the media. There is a nudge to consider just how dependant our view of the present is on artificial constructs such as space and time.

In the end, though, there is never a convergence or resolution brought on during the process of stitching together the pieces of this installation. The elements still resist binding. Holding together only loosely allowing for gaps where shadows, memories, other bits and pieces (and you) can sift through.