Exhibition Essays

The Chinese Horoscope show

March 2012

The Chinese Horoscope show

Matilda Fraser

We do not place such emphasis upon totems as we used to. Perhaps today we are less superstitious than we used to be; in the contemporary secular world, the holy objects of past centuries have become relics, or mass-produced to the point of losing all their meaning. Yet most people still have the same childish belief in luck. A belief that if they perform certain actions or rituals, it will put them in good stead with some sort of cosmic force which might even be able to influence things. I collect four-leaf clovers the way some people collect stamps or post-cards, and anyone seeing them is a little awed by it, as though they believe these arbitrary pieces of plant matter are imbued with something as abstract and subjective as luck. As if a four-leaf clover could change the outcome of my day in any way. But it seems that most people have some kind of totem: an outfit worn for job interviews or first dates, a favourite coffee cup, or small domestic ornaments which one quietly takes note of, reassured by their presence during their day-to-day routines. Some object illuminated by its personal and relational context. These objects rarely make any sense, explicitly, but rather are pieces of the banal, drawn up out of their everyday context and chosen to “mean something”.

There are plenty of established practices that bring the mundane into the symbolic order, thrusting a higher and more enigmatic meaning upon the prosaic rituals of ordinary life. For instance, Western horoscopes and astrology appear to have no rational grounding. Like chukim1, their meanings and significance are independent from everyday value systems and hierachies of meaning. The practice of Western astrology, in its attempt to explain the hidden workings of the world by the positioning of faraway stars, is ludicrous, arcane and beautiful. The particular geography of inattentive balls of fire far beyond the reach of human endeavor is nevertheless part of our everyday, our ecolect, and gives us a navigational tool or a system of recording stories. It is no wonder that people, searching for meaning wherever they could, would try to make sense of the universe in such a way. Chinese astrology is perhaps not so different from any of these systems. Something which—for all its grandness—is best experienced as an undercurrent of daily life.

With this in mind, The Chinese Horoscope Show makes perfect sense in its proposition of uniting twelve artworks solicited from twelve artists, themed around the arbitrary logic of their respective Chinese birth animals. The Chinese Zodiac system might seem to have little bearing upon the lives of most of these artists, given that few of them are Chinese, but what I appreciated was the opportunity for the artists to respond to something which wasn’t necessarily part of their cultural makeup, giving rise to very personal, particular artworks. Viewed together, I thought the artworks looked like a jumble of trinkets on somebody’s mantelpiece. Seemingly disparate, they were connected by the underlying personal histories of each one: of where they were discovered, were they found or purchased or gifted, who was there and what one was thinking at the time. I was struck by the intimacy of each of these objects, obscured like dreams or memories.

Monkey

Kate Woods (WGTN), Untitled, Photographs, fringing, 2012

Kate Woods’s photos, signifying the year of the Monkey, are wonderful illuminations of the banal; a picture of a clothesline against a hedge of leaves is something we do not tend to look at twice. Look again: the leaves are full of oranges, once a symbol of wealth, a once-a-year treat, now a fixture of the mundane, piled up in supermarkets and available in any season. Even pineapples, another embellishing feature in Woods’s other photographs, are imported and for the taking virtually year-round. These photos of (presumably) the artist’s back garden are framed with the Chinese brocade seen in devotional iconography, to further elevate the mundane from its domestic environment and present to us a procession of small, everyday miracles. What I found particularly compelling was the bouncing between high/low/high. The coloured thread worked at once to denote a reverential aspect, while at the same time being reminiscent of the tacky machine-made trinkets available at Chinese-themed shops.

Caroline Anderson with Bek Coogan, Kristen Wineera, Maiangi Waitai, What’s Going To Happen..., Pass the Parcel Performance, February 15, 2012

Rat

Caroline Anderson (NZ/MEL), Too Much Information, Cushions with handmade covers, plinth, workbook pages, paper, glass professor, fake cherries, ephemera from pass the parcel performance, shopping bags, stationery and confectionery, 2012

When viewing Caroline Anderson’s performance piece on the opening night, (the precursor to the installation Too Much Information) I was curious to watch the anxiety of the viewers, how their solemn attention dissolved into uneasy conversation over time. However, the secretive nature of the Rat seemed a little lost in being so overtly on display. This pass-the-parcel ritual was perhaps misinterpreted by the expectant audience, deserving not the hushed silence of a church, but to be treated as part of the general milieu. The work needed to be something to be observed in its turn amongst the artworks, while the ‘rat’ was busily working away in a corner, allowed simply to coexist within this social and relational arena. We have rituals like this every day. The aftermath was preserved as a scrambled rat’s nest overflowing from a plinth, a collection of jumbled objects of diverse value—notebooks, brightly coloured stationery, magazine cuttings, foreign money, and ribbons—like a desk drawer that hasn’t been cleaned out since childhood but which one hesitates to touch. It had a very pleasing and playful tactile dimension to it, full of personality.

Horse

Tiffany Singh (NZ/IND), Never Follow a Straight Line, Dirt, Horse Shoes, Horse Hair, Painted Bamboo Wind Chime 2012

Goat

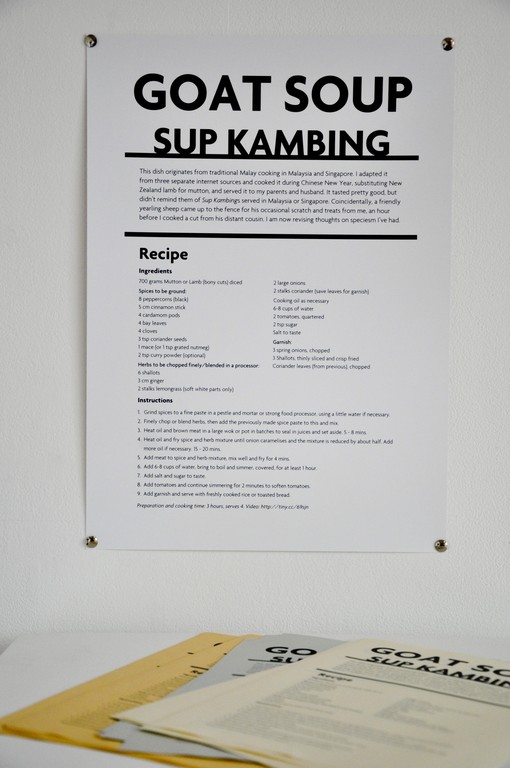

Liyen Chong (AKL), Goat Soup, Printed Paper, 2012

Other elements I was fond of included the simplicity of Tiffany Singh’s shrine to the Horse, composed of remnants of the presence of the animal itself, horseshoes and plaited horsehair, the dirt of its environment, were all arranged painstakingly and ritualistically in an almost pagan way. The show as a whole was syncopated by the ghostly barking from Eugenia Raskopoulos’ Waiting For Lass, anchored by the image of a pair of dogs locked in the entranceway of a house. Like Liyen Chong’s Recipe for Goat Soup, the artist confronted the domestic status of the animal of their birthyear, but unlike Chong’s playful cannibalism, Raskopoulous’s work seemed to elevate the domestic through the medium of video and the context of the gallery space into something quite haunting and ethereal.

![Tiger [left]Chris Lundquist (AKL), Dot. Carnations at 3.37am, Inkjet photograph, 2012 Dog [right] Eugenia Raskopoulos (SYD), Waiting for Lass, DVD duration: 2.38, 2010](/media/cache/16/ed/16edabb70222c2aab1a31a38e43ed5f7.jpg)

Tiger [left]

Chris Lundquist (AKL), Dot. Carnations at 3.37am, Inkjet photograph, 2012

Dog [right]

Eugenia Raskopoulos (SYD), Waiting for Lass, DVD duration: 2.38, 2010

Of all the works, the most compelling was Chris Lundquist’s Dot. Carnations at 3.37am, for its obscurity. A very simple photograph of carnations flung into the night sky, looking as if they were floating in blackness and as polished as a commercial photograph, belied the story behind the artwork. The carnations were representative of the Tiger sign, as was the hour of the morning, but further, the photograph was taken very shortly after the artist’s grandmother had passed away. Death seems to be a time when it is reassuring to lapse into symbolism, into ritual, and these signifiers—carnations and the time of day—came together to tap into both an ancient symbolic order and a very personal experience, yet at the same time implying the universal presence of death. It was the story, in fact, which brought the piece to life for me, the private history behind the work and the elegiac quality of something which could all too easily be taken at face value.

I left with a sense of having been privy to a collection of household magics, quite apt, I think, for a show so based on the personal.

-

1.

A subset of Jewish laws in the Torah which are considered as being utterly, totally irrational, and therefore passed down from God. (Hirsch, 1972, Horeb: a philosophy of Jewish laws and observances. Soncino Press, London.)