Exhibition Essays

TYPEFACE: Enjoy

May 2018

> > ! < <

Tamara Tulitua

TYPEFACE: Live Tattoo Session, opening night, 2018. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Le ‘Au Uso

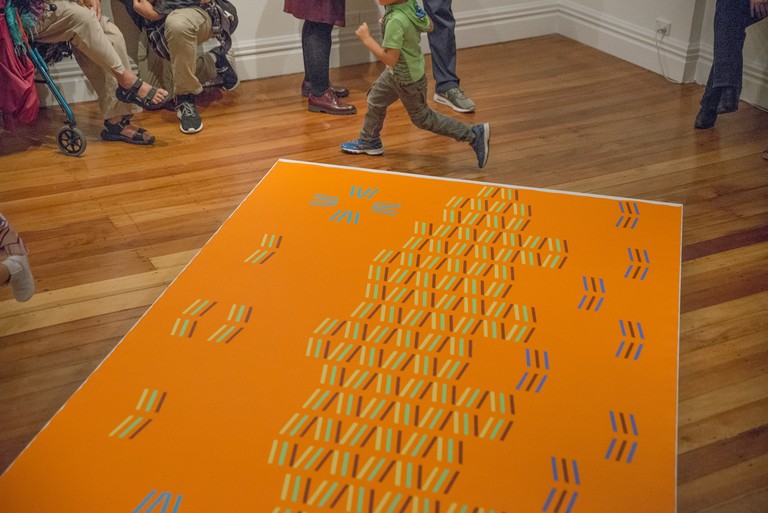

Vaimaila Urale’s project TYPEFACE has travelled across public spaces and gallery walls in Aotearoa and abroad. Her recent exhibition at Enjoy Public Art Gallery had me curious: how would her expansive designs be housed in a smaller, intimate space? TYPEFACE: Enjoy comprised three works, alongside a live tatau on her subject’s chest and sternum completed at the opening. That evening, DJ Linda T’s bold beats provided an appropriate soundtrack to the pulsating works. The event was a whānau catch up over the art table. The audience were lively, head nodding as they nibbled pagi popo and sipped wine. Children twirled around the room and played hide and seek, youngsters gossiped on the stairwell while others talked into a neighbour’s ear while admiring the works. It could easily be Sunday to’ona’i.

I returned to the exhibition a few days later. In the daylight and relative stillness, I considered the pieces as three sisters. They reminded me of my own: the three of us inherently the same, yet starkly different—a mystery of genetic lottery. Three contrasting outcomes from the same equation. I pondered Urale’s process in adorning this space. There was a confidence in laying out a mural on the walls, on hanging Lepo on the floor as if it were a wall. All three felt as if they had been rolled out in the same way one deftly rolls out a fala in a Samoan home—the fala that becomes a bed, a table, a seat. Standing in the middle of the gallery space I asked each piece their name, their purpose. I admired their belonging. Recognised their ease as home to the ancient and new in one being.

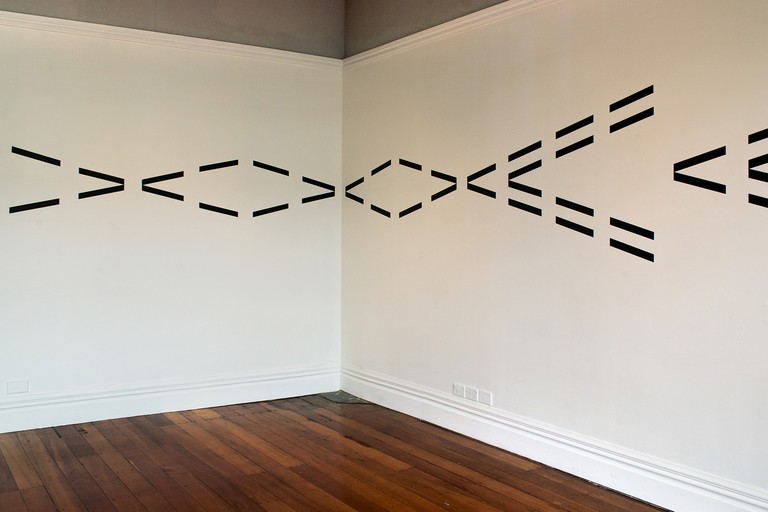

Typeface: Enjoy was the eldest sister, striking in a single flow from the left wall across to the gallery’s windows. Enlarged, black on white, the symbols compelled you to walk along and trace your eye outwards. Doing so felt like tracking an eel flickering under water; calming in its certainty, yet elusive in form. There is no knowing which end is the beginning, or the tail—as soon as you try to figure this out, you realise it does not matter. The contrast is the matter. I laugh to myself as it conjures the same contrasts that would often frustrate me in fa’aSāmoa and the aganu’u. What would seem linear is in fact not so. The eel you follow with certainty may be swimming backward. There was a sense that Typeface: Enjoy was passing through—like a cloud disappearing behind another she seemingly continued, or emerged from, behind, Manamea. She had places to go. You merely caught the trail of her ‘ie lavalava as she strode through, sweet scented laughter behind her.

Vaimaila Urale, Typeface: Enjoy, 2018, vinyl mural, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon and Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

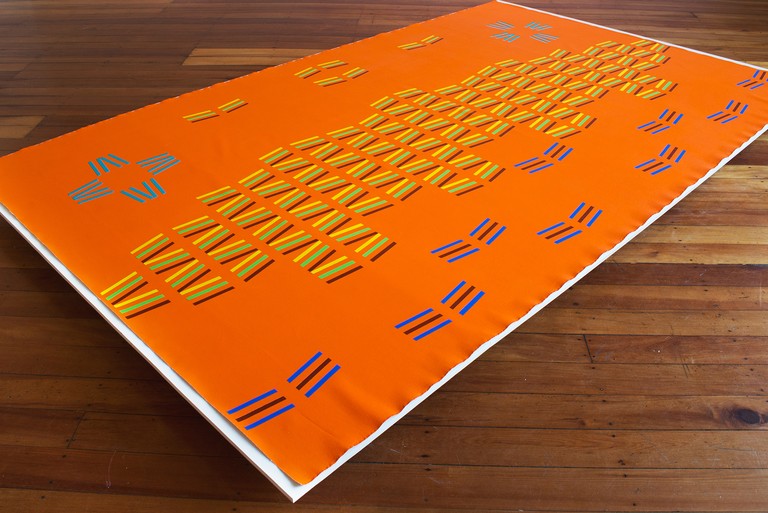

Vaimaila Urale, Manamea, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 1600 x 2500mm. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon and Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

Here we meet Manamea. I was surprised to learn this sister’s name. “Manamea” translates as beloved, sweetheart. Reflex shades of red and lightness bloom when I hear the word manamea. I normally relate it to favourite love songs, or favourite people so named, as it is a popular female name. Urale’s Manamea was stoic with blue and red taimane against a black backdrop. Viewing this piece had a calming effect as the triplet taimane swam in pairs across the surface. My eye played with the patterns of negative space willing the triplet taimane to withdraw then approach me. Repetitive patterns, echoing tukutuku panels, vibrated a grounded confidence. This sister was the Beloved. And she knew it.

Vaimaila Urale, Lepo, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 3000 x 1800mm. Image courtesy of Xander Dixon and Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

Lepo was the proverbial table around which we gathered on the opening night. On my second visit, I had no doubt that she was the spirited middle sister. She has the natural beauty and effortless vivacity that accompanies it. Lepo was fun yet heavy with meaning. I saw two blue stars overlooking yellow and green landscapes. Birds owned the sky between, surveying the playful below. I am a sucker for the bright, the bold and her orange background immediately held my gaze. Her name pricked my ears: Lepo. Was this a play on the words “le po”? I laughed and finally got the punchline. Of course! Irony with a tinge of mockery, the secret spice to Samoan humour. Lepo lay on the floor, stunning. This was no doormat. Or even a table. She lay looking skyward: forward, rising, pronouncing a confident future for strokes of tradition.

Walking Stories

You cannot discuss TYPEFACE without understanding the tradition of tātatau in Sāmoa. Inherent in this tradition is tatau as healer, and as mode of communication. Tatau is a measina (tāonga) of Sāmoa stretching back millennia. One variation of the legend tells of Samoan twin sisters receiving the art of tatau from Fiji where they were told that women receive tatau, not the men. Swimming back to Sāmoa the sisters came across a giant clam and became disorientated. Emerging from the ocean depths they were confused, believing men received tatau and not the women. They returned to Sāmoa sharing the art with two āiga only—some say these were the āiga branches of the sisters themselves. The tatau created were distinct designs for men and women. The tatau for men is called a pe’a; honorific chiefly language refers to the pe’a as mālofie. The female traditional tatau is the malu. Both continue to be a vital part of fa’aSāmoa and are actively participated in in Sāmoa and her diasporic outposts in Aotearoa, United States and Australia.

Pe’a consist of detailed patterns from the mid torso to below the knee. Malu patterns are sparser, spanning from the upper thigh to behind and below the knees. For both malu and pe’a the patterns are always unique. Malu and pe’a further signify traditionally gendered roles in fa’aSāmoa—roles grounded in fa’aaloalo/respect, servitude, duty and honour. They are both sacred rituals of revelation and initiation.

Tufuga tātatau are revered art masters in fa’aSāmoa and are considered to have a certain anointing to perform the art of tatau. Some believe that only descendents of the two āiga who received measina from the twins of legend carry the mantle to perform tātatau. This alludes to the intriguing spiritual dimension of tatau, where the act of marking skin and wearing said marks is one of receiving from the divine. Traditional Tufuga tātatau speak of “seeing” the markings on the canvas before them as and when they are working. There are markings specific to traditional ‘āiga groupings; traditional landholdings and their respective stories. If tatau literally bear the stories of our forebears — breathing, walking Wikipedia of our genealogy and stories—Tufuga tātatau are the storytellers.

Modern Song of Ancient Lines

TYPEFACE carries the ancient practice of tātatau into the now by way of four keys found on any American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) keyboard: / > < and \. Using solely these keys, Urale has created numerous tatau designs. For each design, Urale generates a unique series of symbols, experimenting with colour, scale and context. Through different mediums and applications, these ancient symbols make their way into everyday contexts: public walls, gallery spaces, performances and skin.

On the opening night, volunteer Michelle Healey received one of Urale’s TYPEFACE designs. Performed by respected contemporary tatau artist Tuigamala Andy Tauafiafi, the tatau consisted of two elements on the chest and one down the sternum. The design was overlaid with the conversations between Urale and Healey, all stemming from the vā between them: friends, fellow mothers, Pacific sisters, creatives, all gifts exchanged. Reciprocity: a further element at the heart of fa’aSāmoa.

Tātatau has a distinct tapping sound as the sausau hits the ink soaked ‘au into skin. Tufuga tātatau and their subjects speak of the tapping imbuing a meditative state in the exchange. Tufuga expressing divinity into skin. Speaking of her design process for TYPEFACE and the tatau for Healey, Urale echoes this connection:

When I'm tapping on my keyboard I'm tuning into the volunteer [who will receive the tatau], thinking about how the marks, composition, scale will float on the body . . . I'm working with patterning, a lot of repetition, symmetry . . . it's actually quite rhythmic, definitely meditative . . . I like this idea that I'm working on a A4 template in Google docs, used for writing, a digital form of communication, but I'm also tapping into my heritage to tell a story in my own unique way. I do consider my work abstract and created through an organic process. Basically, I follow my intuition, my instincts, and see where the process takes me.1

Set up in the heart of the gallery, Tauafiafi and his assistant quietly put needle to skin amidst the dance beats, chatter and organised chaos of opening night. Healey was serene as her partner and supporters circled her, fanning with ili and love. Children gathered at her shoulder keen to witness the marking. Phones and admiring smiles flashed; cheeks flushed in the warmth. Live permanent patterns on a living canvas; a Samoan song of Healey’s story. A fourth sister was born.

Michelle Healey, TYPEFACE: Live Tattoo Session, opening night, 2018. Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Mystic Frequency: Out of Time

I am a huge believer in the spiritual dynamic of tatau—contemporary and traditional. This stems from my experience of and witness to a mystic dialogue and spiritual dynamic at play when we express our aganu’u in word, movement, markings, song. This is an expression of the Vā: the space between people, the natural world and the spiritual. These expressions in contemporary context do not mute or lessen its life. It is deeper than tradition or culture: these words fail to encapsulate its entirety. Rather tradition, culture and ritual are its vehicles into the physical. This mystic way washes over me when I listen to lauga of the orators; or through me when I siva Samoa. I hear and taste its timelessness when I listen to indigenous sisters and brothers converse and sing in their native tongues. It does not heed to borders of “discovery” or “civilisation.” This is the space we enter when we reach a milestone in our lives: receiving a chiefly title; tatau; or childbirth and so on. Even in this age cluttered with stuff and noise, there is an unmistakable sense of the collective moving, conversing, dancing, communing on the mystic frequency. Urale and her peer contemporary Indigenous artists make a vital contribution to this movement.

My latest experience of this spiritual connection was in receiving my own contemporary tatau. A personal rebirth last year compelled me to express it on my skin. I wanted the markings to honour my forebears and the courage they give me to express the timelessness I carry. I allowed words to flow from the mystic frequency, penned a poem and asked artist Terje Koloamatangi to interpret this in tatau lines. I chose the heartline/chest as the placement to augment the renewal of sense of self the piece represented. It was an appropriate meeting place on my body to marry the old and new. Aesthetically, as a lover of bold symbolic jewellery, the tatau would be permanent adornment.

Koloamatangi interpreted my lines with his own. What flowed was inevitably a continuation of the divine. On his process as an indigenous artist, he refers to the spiritual frequency as an essential facet to tatau and tātatau:

I do what our ancestors did. I embed motifs and designs into the skin to tell people's stories and to talk about our relationships: with each other, with the natural world and the spiritual world . . . I think there is an element of the spiritual in each piece of work I make, there has to be. We are after all “spiritual beings having a human experience.”

The symbols, ancient and new, all carry something that feels essential. They are loaded, with many stories, with all of our stories, with the past, present and future. They feel timeless. And they speak of stories and experiences that are eternal. I think the idea that we are all looking for some way of making sense of the world and our experience of it and in it through relationship is part of that essential stuff that can be found in tatau.2

Similarly, Urale describes tatau as a storytelling process for her subject but is reluctant to impose her own interpretation of markings on the wearer:

With Michelle [Healey], I knew that she had a partner and two sons so I felt the need to represent them through the marks. I also enjoy that recipients bring their own reading to tattoos. I don't dictate what the tattoo means to them.3

In my experience, the idea of what I believed the markings to express was only a starting point. I was aware of the power of traditional pe’a and malu but I assumed that contemporary designs could not communicate the same way. I was wrong.

The tatau was live with her own leo once she was marked on my body. I did not realise that the piece would in fact be a Healer. She would be Mediator. She would be Teacher. She is storyteller. My mother and I have always held each other in love, believing in our bond despite some miscommunication between us. This faith was rewarded unexpectedly by my tatau. At first opportunity, my mother read the poetry that inspired the markings. Sitting across from me, reading, she was silent. She then studied the lines along my heartline. I watched her intently, sensing an intensity beyond the cafe in which we sat. In that moment, it was as if the disconnected cables of knowing interlocked with instant, powerful currents of healing; a rush of understanding. All without words. Clarity. Power. Love. With it came a reconciliation to my mother’s lineage and her mantle of carrying our ‘āiga stories, which I had unwittingly held at bay. I knew in that timeless moment I held them in trust for my daughter and thereafter; a link in our matriarchal line. My mother studied the markings and literally spoke with them. I wanted her to tell me in words—I craved verbal, out loud declarations of love. But she simply nodded. Heeded the mystic speaking and made me listen too. Healer. Mediator. Teacher.

Beyond Measure

During this year’s Sāmoa Language Week (May 27 – June 2, 2018) there was lively discussion about the vitality, or demise, of our language, Gagana Sāmoa. The statistics paint a bleak picture—despite a large Samoan community in Aotearoa, there is a decline in Sāmoa language speakers. Linguistic academic Dr Salainaoloa Wilson’s valuable research looks into the state of the Samoan language amongst the younger Samoan generations.4 She discovered young people who considered Gagana Sāmoa as irrelevant and without career prospects. They noted its relative silence in the digital world. Dr Wilson’s research focussed on the obstacles Samoan students faced in attaining or retaining Gagana Sāmoa and offered pragmatic solutions to enhance and embed language in younger learners.5

As a receiver of aganu’u despite being “New Zealand born” I am hard convinced of the extinction alarm raised for our language. It has survived for millennia, are we really capable of dropping the ball now? Urale’s work addresses this head on, placing the traditional and ancient confidently in the current, living and modern. Herein lies the relentless optimism of TYPEFACE: tatau, like all measina and its spiritual dimension, is not fixed. It is not stuck in museum collections, rendered in 2D ink in dusty shelves. It exists first and foremost in us. Perhaps death comes only when there is no one in existence who can carry our ancient knowledge and facilitate its dynamic nuance. Even then, this apparent death would be temporary—a forgetting. Losing our way. As the revival in various Indigenous practises has shown, we can find our way to our spiritual home. Contemporary artists, young avid learners of Gagana Sāmoa and everyone in between offer the same passport to the mystic frequency. Physical obstacles certainly exist—but extinction is implausible and a falsity.

Live Leo in Perpetuity

Indigenous knowing and understanding cannot be wholly written nor measured. The more I learn about tradition and culture, the more I am convinced that there is an element of indigeneity that cannot be grasped in such discussions. I believe there is an inextinguishable essence of indigeneity that persists in native peoples. It is this essence that survives outright genocide by colonialism. It is the essence that persists in the children of the perished, who are now intent on reviving, restoring, discovering, pursuing—and indeed revelling in—their indigeneity. Generations of colonialist, neo-colonialist, imperialistic agendas have not—and arguably cannot—extinguish this remnant spirit.

TYPEFACE gives voice and space to this enduring spirit. Koloamatangi too asserts this endurance in his practice, warning us of the reductive language in what we perceive as “traditional”:

. . . it is important to consider that what we refer to as “traditional” symbols are only a snap shot in the history of our customary tatatau. There were symbols before the “traditional” and artists/tufunga today continue to evolve our symbols/designs/patterns and I believe this will continue to happen into the future.6

TYPEFACE reminds us that such communication is not binary—neither old or new, obsolete or relevant, current or expired. It is multiple, dynamic, live. TYPEFACE is an emboldened and beautiful leo that joins the never-ending chatter of indigenous revival and celebration.

For our people, the information age was not the first time of multi-platform communication. We have long carried song and story, preserved genealogy, land and title succession by way of oratory, song and dance and tatau—the eternal interplay between the celestial and the physical. Urale’s work reminds us of this never-ending line. It acts as a conduit for communication between traditional and contemporary, preserving culture. It directly rebukes any commentary that considers traditional culture unmoving, irrelevant or boring. It heartens when the statistics and its underlying causes are revealed. Relevance. Relevance. Relevance. If our young people are asking how can our Gagana—and implicitly aganu’u—be of any use in the now, TYPEFACE responds.

Acknowledgements

Fa’afetai lava Lemalu Sea Tulitua for her advice on fa’aSāmoa content; and for her generous permission to share our story.

Malo ‘aupito Terje Koloamatangi for his insights and recommended texts.

Recommended Reading/Viewing

Online Articles:

Makuati-Afitu, Barbara. “The art of Samoa and tātatau and tatau (tattooing and tattoo).” Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, 25 May 2016. http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/collections/topics/the-art-of-samoa%E2%80%8Bn-tatau%E2%80%8B-tattoo

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. “Samoan Tatau (tatooing).” Accessed 27 July 27, 2018. https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/1560

Documentaries:

Taouma, Lisa. “Tatau - A Journey Part 1.” Director by Lisa Taouma. Edited by Keng Lim. YouTube video, 20:22. Posted October 31, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSipc5t_4Gg

Taouma, Lisa. “Tatau - A Journey Part 2.” Director by Lisa Taouma. Edited by Keng Lim. YouTube video, 25:35. Posted May 19, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQRyUtx9cy8

Urale, Makerita. “Savage Symbols.” Produced and directed by Makerita Urale. Edited by Tamara Finau-Moir. NZ On Screen video, 55:00. Origionaly screened at the 2002 NZ International Film Festival. https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/savage-symbols-2002

Texts:

Ellis, Juniper. Tattooing the World: Pacific Designs in Print and Skin. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Galliot , Sebastian and Sean Mallon. Tatau: A History of Samoan Tattooing. Wellington: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2017. Purchase online: https://www.tepapastore.co.nz/products/tatau-a-history-of-samoan-tattooing

Gell, Alfred. Wrapping in Images: Tattooing in Polynesia. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Marquardt, Carl. The Tattooing of Both Sexes in Samoa. Papakura, New Zealand: R McMillan, 1984.

Thomas, Nicholas, Anna Cole and Bronwen Douglas (eds). Tattoo: Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

-

1.

Vaimaila Urale, email message to author, July 24, 2018.

-

2.

Terje Koloamatangi, email message to author, July 27, 2018.

-

3.

Vaimaila Urale, email message to author, July 24, 2018.

-

4.

Dr Salainaoloa Wilson, “A malu i fale le gagana, e malu fo'i i fafo: The use and valuing of the Samoan language in Samoan families in New Zealand”(PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2017), pp 3–5 (re language statistics).

-

5.

Wilson, “A malu i fale le gagana, e malu fo'i i fafo,” pp 195–207 summarise Dr Wilson’s findings.

-

6.

Terje Koloamatangi, email message to author, 27 July 2018.