Exhibition Essays

Brave Days

March 2008

Wires, Sticks and Suspended Belief

Gabrielle Amodeo

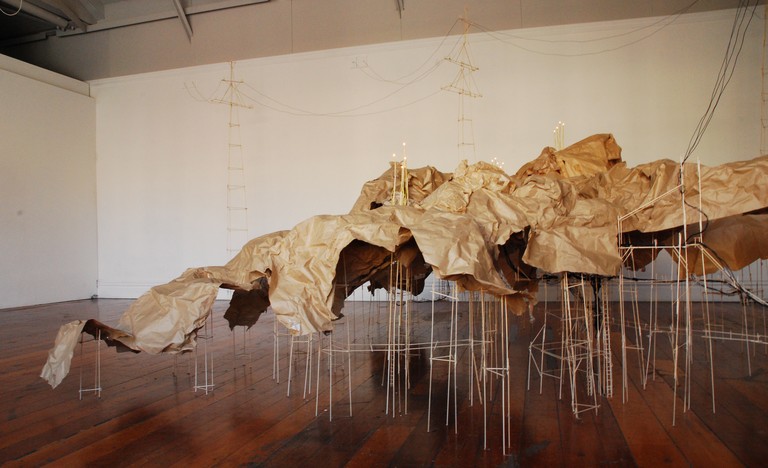

It is, in the archaic sense, a conceit. It would be a heresy to conceive of a landscape like this in another, superstitious age - a world carried on spindly legs, with power pylons beyond the rim, ladders leading from the underbelly and birthday cake candle-like lights. Joanna Langford's exhibition Brave Days was an installation of a landscape held up by wires, sticks and suspended belief.

In correspondence with the author, Langford wrote of an interest in landscapes and expeditions. "The notion of journeying and exploring influences me, especially the mystery and romance attached to the early European pioneer pilots and epic expeditions, when explorers were beginning to understand the physical skin of the world ..."In the golden age of European exploration, myth and reality were often confused - as seemingly logical, well-educated men dashed off into the unknown, to search for El Dorado and the like. What they found (aside from foreign diseases) were lands sans streets-paved-with-gold but equally dazzling for other reasons. Tundra deserts, wastelands of ice and snow, lands carved up by monstrous geothermal activity and lands with beguiling ruins from ancient civilisations: these are landscapes that, in a strangeness grounded in reality, become more fantastical than myth.

The feel of Langford's resulting landscape seems at odds with what the work is made from. Langford collects the detritus of daily life to make her work. Her manipulation of materials has a transformative element. Brave Days hung in the air with the sparseness of a drawing spatially realised: the bamboo sticks and wires coupled with the brown paper became equivalent to the coupling of line and tone in a drawing. Beyond this, the scale of the work transforms the accumulation of rubbish into an outlandish terrain for the viewer to reflect on. Spanning the gallery space and towering to the rafters at the tallest point of a rickety power pylon, the size of this landscape interacted with the human form and distorted the fact it was a carefully compiled stack of humble odds-and-sods.

It is within these twists that Langford's conceit invites further conceits from the viewer. Brave Days prowls the border of reality and fantasy. My perception of the installation oscillated rather wildly between a peculiar upside-down and back-to-front landscape, and an entirely anthropomorphic response. Brave Days plays with the relationship between a landscape and the human interventions placed within it. The otherworldly scaffolding that holds the landscape up becomes part of the structure of the land rather than a human intervention. It becomes something grown rather constructed - a land that has evolved its own lights and power pylons. Tue installation morphed into a reptilian or serpentine creature crouched in the gallery space, shackled to quixotically conceived power pylons; the rhythms of its body (if it were to move) would be a rickety undulation.

The overarching feeling of the work was something that was somehow tinkered into existence. The manner of its construction has the sensibility of those explorers' expeditions: romantic and impractical. Duly Brave Days appeared delicate, unrealistic and teetering on collapse. The seeming fragility lends a vertigo-inducing height to Langford's towers of sticks and the lights look less assembled, and more grown like a bean sprout. Is it a sign of the times that I look at Langford's impracticable power pylons and have to check myself from thinking about the consistency of supply in her made-up landscape? I am left wondering who is in charge, and whether they have really thought it through. The fact that these whimsies work, the towers defying gravity and carrying electricity to the lights, lends the work an uneasy suggestion of something living within it.

Brave Days elicited memories of an autumnal Desert Road, brown, textural and bare, pockmarked by stalk-like power pylons. Aside from physical attributes, there is a particularity to both Brave Days and the Desert Road; an emptiness made profound by evidence of existence. In both situations, traces of existence give a tangible presence to something that is not there. A trace can represent the absence of something that was present, however, it fully marks neither presence nor absence (as what left the trace was, at a point, present) but a trace can operate as both.

Along the Desert Road, signs reminding drivers they are passing through an army training ground and duly ought not stray off the road call into being the potential of camo-clad lads hidden along the road side. In the same way, Langford's power pylons and intermittent flashing lights suggest the possibility of something living within her constructed landscape. The Central Plateau's soldiers have a latent presence because thcir traces play across the landscape even in their absence. The soldiers are at the same time absent (through not being visually apparent) and present (through the trace). Similarly, the traces of humanity in Langford's work have the ability to suggest life. The installation's suggested rather than real presence implies Brave Days as a living space.

Langford's installations often use the hallmarks of existence, objects the viewer can look at and under stand as a representation of an inhabited landscape. The place becomes something for the viewers to project onto, but not to inhabit and be within themselves. This becomes a form of archaeology.The viewer can don their fedora and examine Langford's landscape, consider the abandoned structures and speculate on theories and meanings of the artwork, but unlike the inestimable Dr. Indiana Jones, cannot be a part of it. Like a story, it can be read, thought about, built on with the viewer's imaginings but the viewer does not occupy it.

Through this, Langford's work explores the intricacies of place. Brave Days interacts with the gallery architecture in fluent and poetic ways. However, rather than transforming the gallery space into some thing else, she constructs a 'place' that inhabits the gallery.The gallery is exclusive from Brave Days even though it dwells inand on the gallery's structures. The Enjoy gallery space, in an almost organic sense, hosted Brave Days.

The relationship between the gallery and Langford's construction parallels a mythical landscape residing within a culture. A myth sits within a culture, working from the structures of a culture: fuelled on rumour a myth occupies a culture's imagination, but it is held separate from reality Brave Days becomes similar to those mythical landscapes because rather than the viewer being able to occupy the work, the work occupies the imagination of the viewer.

-

1.

Conceit is now a sadly flattened word. In this instance, a conceit (in the archaic sense) is an object created from the imagination. It is to conceive of something poetic, iaginative, far-fetched. It is about wittiness and inventiveness of expression.

-

2.

The Desert Road runs through New Zealand's Central Plateau, an alpine semi-desert that contains New Zealand's largest military base.