Exhibition Essays

Huia me ōu whetū

May 2021

Huia me ōu whetū

Mya Morrison-Middleton

Ngā whetu provide navigation for our waka to traverse Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, and beyond. They help us sequence our time, month to month and year to year. Dr. Rangi Mātāmua describes the constellation Te Waka o Rangi as a waka with Matariki at the front and Tautoru at the back.1 It is captained by the star Taramainuku who casts his net down to gather the spirits of everyone who dies each day. When Te Waka o Rangi sets, during the month of Haratua, Taramainuku then carries the spirits to Rarohenga. When it rises again in Pipiri he releases them into the sky to become stars. Mātāmua links this to the origin of the whakataukī kua wheturangihia koe (you have become a star). Grace tells me I was the person who introduced her to full astrological star charts. I’m slightly embarrassed by this, but will admit I think stars are great.

Turumeke Harrington and Grace Ryder, with friends Sarah Hudson, Saskia Leek and Kristin Leek, and Greta Menzies, Help Yourself, 2021. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Help Yourself is a group exhibition co-authored by artist Turumeke Harrington (Ngāi Tahu) and curator Grace Ryder. Help Yourself is held together by care, friendship and reciprocity. For Help Yourself Grace handled the administrative load while Turumeke gave the exhibition a scaffolding of visually cohesive work within which to host other artworks. Cushioned by their friendship and mutual dedication, Grace was allowed capacity to extensively research and read (something we agree is a rarity in the non-stop churn of current working conditions) and Turumeke had the rare freedom to simply make.

First meeting visitors to Help Yourself are Turumeke’s You [I] Can’t Be (All Things To All Men) Chillout Sessions Vol. I-XII, a series of baby blue banners embroidered with various constellations of shapes—penises, mouths, vulvas and stars—in polyester tent-like fabric. I heard the stars were buttholes, but Turumeke seemed irritated when I asked. These embroidered constellations as an entrance point remind me of carved pare that sit over entrance ways, their figures placed, legs wide open, showing off delicately carved genitals front and centre. Pare often guard the entrances moving from noa to tapu spaces, as you enter under the genitals of the carved figure you are entering the source of whakapapa. I remember the news stories which occasionally pop up about carvings having their genitals chiselled off by renegade prudes with a missionary hangover. I wonder if Māori have unashamed fun depicting genitals because we’re all about whakapapa.

![Turumeke Harrington, You [I] Can’t Be (All Things To All Men) Chillout Sessions Vol. I – XIII, 2021, polyester fabric and cotton thread, steel. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.](/media/cache/8f/4a/8f4adfaafe26427bce9d88fa6992cc14.jpg)

Turumeke Harrington, You [I] Can’t Be (All Things To All Men) Chillout Sessions Vol. I – XIII, 2021, polyester fabric and cotton thread, steel. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

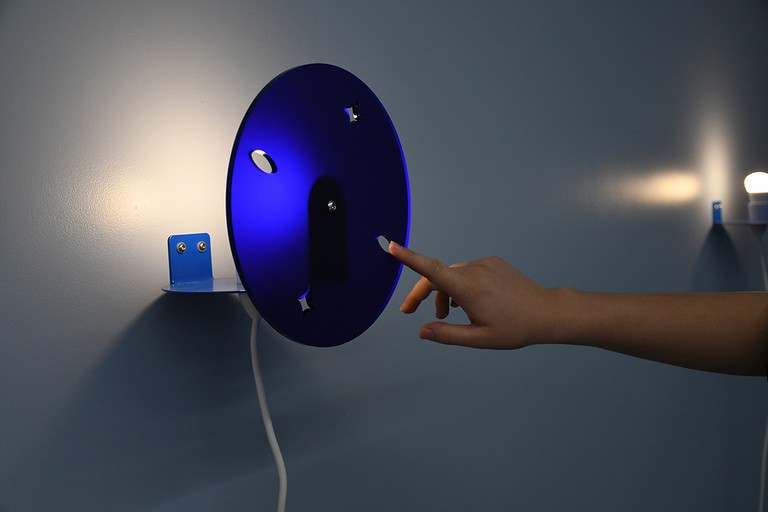

I’ve been thinking about creation stories, the tihei mauri ora that brought Hine-ahu-one to life and of Whānui the star parent of kūmara. Star dust is one of our oldest origins. Further into the next room Te Tauwhirowhiro Maruwehi (Can’t hold this sunny disposition back) I-XII, a series of electric light fixtures, line the walls. The sconces feature more genitalia and stars, laser cut out of acrylic perspex and wired with bundles of thick white extension cord twisting along the floor. The circular light shades on the sconces rotate, shifting penis-penis-star-vulva, like a stereoscopic View-Master flicking between slides. The signature visual language Turumeke has developed through materials, colours, form and design is deployed here and I appreciate the rare and important invitation to wonder and laugh within Turumeke’s work. She has mastered a balance of sharp satisfying forms and playfully inviting materials and colours. It’s not enough to say this is simply good design, every element is cohesive and considered in this install by Turumeke. The symbols cut from the sconces are proportioned just right, and the perspex is just the right magnetic shade of cobalt glass blue. The thick white wiring of the sconces tumbles around the gallery floor just right. The baby blue painted walls, the banners, and deep dark blue of the perspex light shades accentuate each other, together, just right.

Turumeke Harrington, Te Tauwhirowhiro Maruwehi (Can’t hold this sunny disposition back) IX, 2021, steel, acrylic perspex, LED light bulb and electrical wiring. Exhibition opening, 27 May 2021. Image courtesy of Tom Denize.

Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Pūkeko), Saskia Leek and Greta Menzies were invited into Help Yourself with the proposition to make something for someone, or with someone else in mind. Sarah’s Reunion is a piece of Ngāti Maru ki Hauraki whenua resting on canvas dyed with Ngāti Pūkeko earth pigment. This work draws from the extensive research Sarah has been doing with whenua as art material and practices from tīpuna tawhito. Sarah is well versed in the value of collaborative practice, being a part of Mata Aho and Kauae Raro Research Collective. Sarah created Reunion for a fellow collaborator because while collaborating they discovered they share whakapapa—I assume through Ngāti Pūkeko and Ngāti Maru ki Hauraki. As iwi Māori, connecting with whanaunga is a potent form of healing and care. The reunion of tīpuna, whenua and continuing of whanaungatanga has effects extending deep into the past and infinitely into the future. Shared belonging to awa, whenua and waka is a bond between people which is hard to describe. I guess I would just say the practice of kotahitanga, whakapapa and mana whenua are existential purposes. I think of Hine-ahu-one, the first woman formed out of clay and of the word whenua itself, also meaning placenta, which is planted into the earth to maintain our connection to Papatūānuku. I think of the ways the Crown has tried to extend authority through quietly written laws and renaming, and the comparative violence of the mass extraction from and pollution of our many ūkaipō. The whenua here is attributed in name to the hapū who belong to it. How much land could be reunited with its rightful carers, a handful at a time, before the Crown noticed? Like, literally land back. Handful by handful, lot by lot, title by title.

Sarah Hudson, Reunion, 2021, Ngāti Pūkeko stained cotton and Ngāti Maru ki Hauraki whenua, detail. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

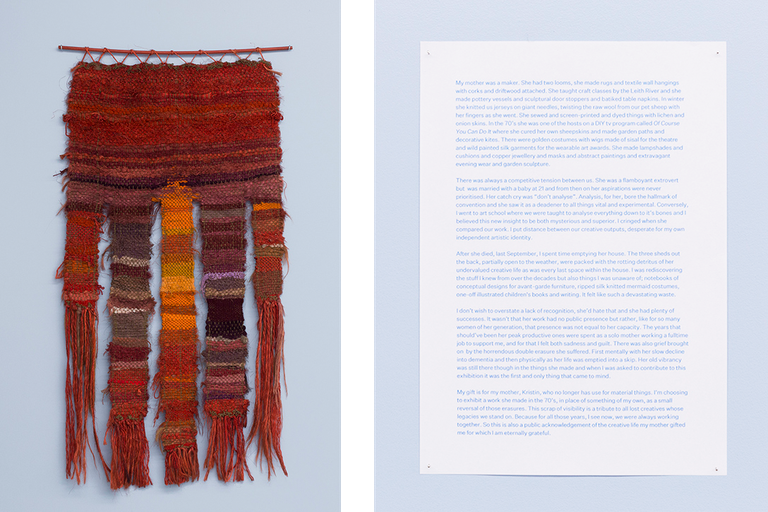

Saskia presents the work of her late mother Kristin Leek; a woven hanging textile in shades of terracotta and deep reds. Accompanying Kristin's work is a text by Sakia, pinned to the wall and describing the complicated relationship between them as mother and daughter and as artists. Saskia has quietly shifted here, from her renowned painting practice, offering in the text a direct address to us about the interior and exterior complexities of relationships and art making. In the text Saskia declares “This scrap of visibility is a tribute to all lost creatives whose legacies we stand on.” Saskia notes the relegation of craft practices, particularly potent here with the historical relegation of textile practices, and her mother’s aversion to analysis, something which divided them. I sit wondering for a long time what my own mum—as someone who went to art school and had an art practice as a solo mother—makes of my career. I’m faced with questions I have been mulling over for the past year “Who is benefitting from my output? How do I find purpose in my output? Is all this energy feeding my life as a whole person?” Amongst this show's celebration of care and acts of service, here is a shadow side. Martyrdom and the sacrifices often involved in motherhood can deepen gulfs between family members. Similarly unfair sacrifices can divide friends, artists and peers. This work still hits me, searing in my chest, each time I recall it.

Kristin Leek, Wall hanging, c.1975, mixed media. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Saskia Leek, My mother was a maker, 2021, text, A4 paper. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Grace mentioned reading about Eros and the different types of love enumerated in Ancient Greece. I associate the philia type of love (an earnest affection led by care and a strong bond) with Turumeke and Grace’s collaboration. Grace tells me Greta was involved in an accident just before the exhibition, and I infer that Greta, in an act of philautia (love defined by caring for the self), created the soft woollen sculpture Happy Talisman dotted with glass bead smiling faces. I wonder if this is a gift to call in joy for someone (potentially herself) in a time of hardship.

The second piece Lucky Janus is a vessel with seven handles, and faces almost camouflaged within the porous looking glaze between each handle. Janus is the Roman god attached to new beginnings and change, it is also the name given to one of the inner moons of Saturn. These works continue a curious interest in Greta’s art practice with religious symbolism, customs and the attribution of collective meanings. There are so many ways we attribute meaning in the world around us, and in ritual practice we consciously and unconsciously do. There is power in our symbols, especially when we pull them in to influence our relationships with others. I imagine the great amount of co-operation needed for seven people to use this vessel at once. I wonder about the significance of seven handles and the number seven itself. The seven sisters of Pleiades come to my mind along with the seven days of the week, seven hills of Rome, seven deadly sins and Lucky 7 pokie machines. I wonder most who this piece was made for.

Greta Menzies, Lucky Janus, 2021, black anthracite clay. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Rehua is significant for many reasons, but I understand him as the atua of manaaki who reminds us of the importance of kindness and care for healing. Rehua lives in the highest celestial planes, he is the star also known as Antares. Turumeke and Grace propose friendship as resistance. Nourishing each other as resistance. It’s punk to do things for friends. I agree. Reciprocal pastoral care is radical in response to the (at times) treacherous, sometimes totally weird and very specific working conditions of the art industry. Friendship is necessary, where (often) non-existent human resources departments or the precarity that defines freelancing fail us, it is a salve. We need our friends, who understand these strange working conditions, to confide in or to reality check complex situations. Friends are solid companions alongside quickly arising and evaporating exhibitions and projects.

I asked longtime friend and occasional collaborator Piupiu Maya Turei, “Why do you collaborate with your friends?” Piupiu makes music, art, and events in the collaborative duo E-Kare with her husband. Piupiu and I were friends when MSN and Neopets were the top social media, so we’ve been through highs and lows together. Her initial response was similar to my own—“because it’s fun”. Piupiu and I talk about the different ways of collaborating, about creating environments where people can make work by helping with domestic chores, being a listening ear, turning up to serve food at their openings or holding a hammer during install. Cultivating those ripe conditions of manaaki is what Turumeke and Grace have done for each other.

Turumeke Harrington in collaboration with Abraham Hollingsworth, Hers & Hers, 2021, American ash, polyester, steel and foam. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Turumeke’s Hers & Hers (in collaboration with Abraham Hollingsworth) is here in support of the artists, artworks and audience. A pair of wood frame seats, covered with cylindrical baby blue cushions fastened by D-ring lashings, are placed in an ideal viewing location to sit back and admire the rest of the exhibition. Turumeke has created the lighting, the seating and the entry point, so basically the bones of the show. When she first introduced me to Help Yourself, Turumeke simply described it as making furniture for Grace’s home. “Grace needs a lamp, so okay I’ll make some lamps.” Turumeke’s works might live in the homes of friends and family, and then be redeployed again as art in a gallery. The orbit of these fluid art objects through friends' homes is similar to the way taonga are deployed from museums to events, collecting stories and bonds. This valuing of bonds drives Help Yourself. It is a blue show because Grace likes blue. All the banners in the front gallery are the same height as Grace. These reasons could seem flippant in comparison to the supposedly lofty academic reasoning we are used to, but thinking that devalues our foundational relationships. I imagine Grace and Turumeke lounging on these seats in Grace’s house, for months or years in the future. These chairs are then a site to hold the nurturing of a relationship and shared practice. I am reminded of artist Ayesha Green unashamedly owning love as an artistic ideology, “I feel like there has been affirmation, that talking about love and care is an OK thing to be doing in regards to, and in relation to, colonial struggle. I feel reassurance that love can be a foundational ideology in making work." 2

Turumeke Harrington, Te Tauwhirowhiro Maruwehi (Can’t hold this sunny disposition back) II, III, XII and VI, 2021, steel, acrylic perspex, LED light bulbs and electrical wiring. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Grace told me a story about a friendship bracelet she made at Ed Ritchie and Megan Brady’s artist talk and friendship bracelet making event for Lay in Measures, earlier this year at Enjoy. During the install for Help Yourself, Grace’s friendship bracelet fell into the gap between the gallery floor and the gib wall lining, but was still visible, at least at floor level. I imagine Grace’s friendship bracelet, set within the walls, but still radiating throughout the show. I switch between being sickly-sweet earnest with my friends and then totally averse to sentiment, behaviour I identify between Grace and Turumeke, too. But Help Yourself is absolutely, a sickly sweet homage to the friendship between Grace and Turumeke, and their relationships with Saskia, Greta and Sarah.

In our conversation Piupiu used the analogy “All the uncles will come together and build a tree hut for their kids, and then all their kids can play in the tree hut. It’s like whakawhanaungatanga.” We both agreed an insular art practice would probably get lonely. The time we spend doing things together is really the most valuable part of making.

The kupu te Reo Māori for “constellation” are characterised by closeness, terms like huihui, whānau mārama, kāhui whetū and finally tātai whetū. There is whanaungatanga within our stars, scattered far across the sky but still connected. Similarly our loved ones are scattered across the planet but we still orbit each other. My sense of awe when admiring the night sky and its heavenly bodies is similar to the awe when admiring the people who surround us to support our art practices. Huia me ōu whetū, gather with your stars!

Note: This essay previously appeared under the title Huihuia ōu whetu. This has been corrected following advice from Tipene Walters, my Te Reo kaiako. Ngā mihi Tipene for looking out for your tauira! Mya.

-

1.

Rangi Mātāmua, “Living By The Stars Matariki Webisode 2 - Matariki Tohu Mate,” November 17, 2020, video, https://youtu.be/mxigZDJIpbM

-

2.

Ayesha Green, ”Interview,” ATE Journal of Māori Art Volume Two (2020): 36.