Exhibition Essays

Ancient and Lively

September 2022

Ancient and Lively

Rosie Stack

Nestled in the foothills of Te Ahumairangi ridgeline, a cottage and garden in a narrow Thorndon street was a place of peace and sanctuary for the artist Rita Angus. Built in the 1870s, its simple timber structure appealed to Angus’ socialist philosophy, and the surrounding hilly topography offered inspiration to her painterly eye. The cottage has undergone very few modifications since its construction. The Rita Angus Cottage remains, as it did for its namesake, a refuge from the pace of modern life.

The exhibition Through Claystone Eyes emerged from Eleanor Díaz Ritson’s time as Enjoy’s summer resident at the Rita Angus Cottage in early 2022. Conceived of during her time at the cottage and worked on over the following months, the ten paintings of Through Claystone Eyes also move at their own pace. The mostly figurative works are at a scale just larger than life, painted in small textural brushstrokes with desaturated water-mixable oil paint. The process of their creation is not fast work. In fact, Díaz Ritson likens her experience of painting to that of the Earth’s geologic cycles. Painting, she says, is a practice in engaging her own claystone eyes. 1

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Furrowing Wayfarer, 2022, water-mixable oil on canvas, 150x165cm (detail). Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Claystone is a fine grained sedimentary mudrock. Not generally known for its artistic or aesthetic value, the material has found recognition for its ability to record past environments and life forms. Claystone’s fine grains form a perfect layer around soft bodied organisms, holding their fossilised bodies safe from cycles of erosion and movement for millions of years. In this, claystone acts as a kind of archiving force, collecting and protecting evidence of past life as precious artefacts within layers of rock.

In archiving these bodies of deep time, claystone and other mudrocks proved crucial to the development of an awareness of geologic and non-human timescales. By the nineteenth century, European researchers had found that the most reliable way to read and date the geological record was to correlate it with the biological one. Differences between fossil deposits became key to identifying and dating geological strata, prompting scientists to formulate a history of the Earth that came to extend over billions—rather than thousands—of years. John Durham Peters claims that, for these early earth scientists, the planet’s geology came to function as a recording medium, likening their vision of the Earth to that of “a library in which the books have been pillaged, scattered, censored, and burnt.”2 Ancient fossils which had for aeons lain blanketed in soft sedimentary stone were the inscriptions on its muddy pages.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Earth’s newly recognised ability for self-documentation not only alerted scientists to what we now call ‘deep time’, but also raised questions as to the motions of geology itself. Charles Lyell—commonly recognised as the founder of modern geology—offered explanation through a theory of slow but continual planetary change. Rivers carving out valleys over millennia, volcanoes emerging as ruptures in the Earth’s slowly moving crust. We can, Lyell claimed, witness the workings of deep time through the geologic formations they leave around us.3

At the time of Lyell’s writing, instead of taking up his invitation to imagine the Earth’s past through its present geology, many European artists turned their eyes to the future, imagining scenes of their own societies collapsing into the earth.4 Romantic artists toured Europe in search of picturesque ruins from which to draw inspiration. In Gustave Doré’s etching The New Zealander (1872) a romantically clad Māori figure perches over the falling ruins of London. The idea of a future antipodean archaeologist visiting the ruins of the ‘old world’ became such a popular motif that it was labelled cliche by newspapers of the time.5 Lyell himself opened his canonical Principles of Geology (1832) with an illustration labelled the ‘Temple of Serapis’, depicting the crumbling columns of the once great Roman marketplace in Pozzuoli. It can be easier, it seems, to imagine the end of one's own civilisation than to imagine a new set of relations to a simultaneously lively and ancient Earth.

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Unsettled Witness: in the Fall,Together, 2022, water-mixable oil on canvas, 150x165cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

In the twenty-first century we have again found ourselves in a period where knowledge of planetary change is prompting contemporary artists to imagine the eventual fossilisation of our own society. The first artwork encountered by the visitor as they enter Through Claystone Eyes seems to engage in this pre-emptive memorialisation of a soon-to-be fossilised humanity. In Unsettled Witness: in the Fall,Together two figures kneel in shallow water, supporting a third collapsed body. It seems all colour has been sucked from their world. The painting’s dark sky and ghostly figures evoke imaginings of some post-apocalyptic future, with smog and pollution too dense for sunlight to penetrate. At such a large scale this scene assumes a mythic quality. One finds themself creating stories in an attempt to account for how, and why, these people came to be in such a desolate environment. Are these figures facing their doom in this new cycle of the Earth’s history, soon to be encased as another illustration in its scattered pages?

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Vision Through Claystone Eyes, 2022, water-soluble oil on canvas, 145x135cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

This scene of drowning decay is repeated in Vision Through Claystone Eyes. In a similarly desolate seascape, a singular figure is caught in a moment of revelation, her eyes turned to the lightless sky. Within the cave-like atmosphere of the gallery’s back room her body is initially indistinguishable from the rest of the canvas. It is only when one has allowed their eyes to adjust to its darkness that she appears. First as another of the seascape’s jutting rocks and then—as if emerging from the land itself—there is a face, a hand, and that visionary gaze. Having just emerged from the dark canvas there is a sense that we may be witnessing her first, not last, breath. Perhaps the tale we find ourselves looking for is not one of apocalypse, but rather of primal creation; a story that can explain the moment when clay becomes eyes, just open, though not yet fully of human flesh and blood.

Such creation scenes are familiar, the emergence of life from clay is an origin story of humans in many of the world’s religions and mythologies. In classical Greek mythology Prometheus is said to have formed man from mud, with the goddess Athena or the wind breathing life into the figure. In his second attempt to create living beings Viracocha, the creator God of the Incas, uses clay to make humans. In Chinese mythology Nüwa, the mother goddess, moulds humans from yellow earth and gifts them with fertility. In these stories the symbolic inanimacy of clay serves to emphasise the miracle of life. Breathing, dancing, fighting, sentient humans are somehow drawn from the relenting and flaccid material.

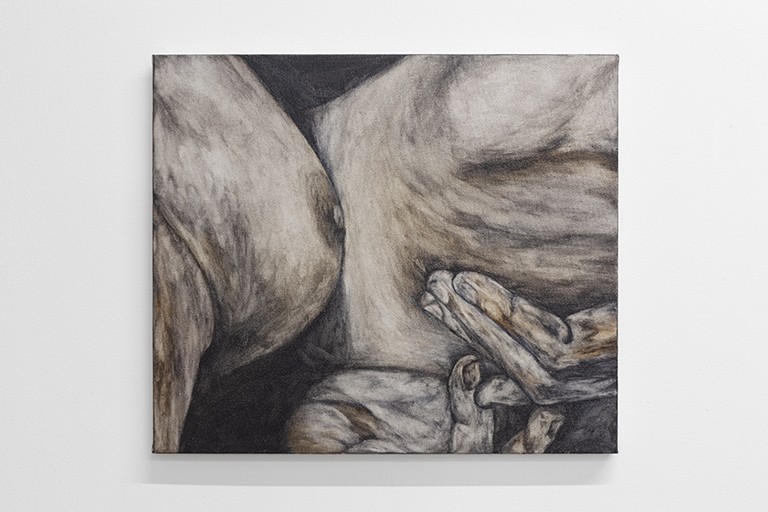

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Close, 2022, water-soluble oil on canvas, 30x35cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Through Claystone Eyes is littered by a number of smaller paintings that, in contrast to the bleakness of the seascapes, seem to celebrate these lively aspects of human existence. In Close the torsos of two bodies are caught in a moment of embrace or the act of making love, breast pressing into shoulder, hands clutching for the other. Stories of the miraculous birth of humans from clay are often followed by coupling and procreation, the capacity for love, desire, or the pursuit of pleasure markedly separating the newly animated humans from their inorganic beginnings. But within the geological contexts of Through Claystone Eyes, there is a struggle to read the relationship between the bodies of Close as purely ‘human’. The pressure between the figures evoke myths of the splitting of earth from sky. In Aotearoa we may think of the division of Ranginui and Papatūānuku, the way their bodies would have pressed to each other and the life that became possible through their separation. The sensuality of the painting is not lost in this (literally) earthy interpretation. Rather, its generative and even erotic life-giving motion becomes shared by both the earth and the human body.

As Díaz Ritson has shared, her paintings do not arise from an understanding of the earth as dead, rather from a knowledge of “both body and place as lively”.6 A duo of smaller Cuerpo-Cueva (Cave Body) paintings tussle before the viewer, their forms fluctuating between body-scape and land-scape. What at first seem stomach and thighs become a moonlight hillscape, rolling earth in turn becomes puckering skin. Wrestling between body and land, the cave bodies never lull long enough to become fully either. The turbulence of these scenes alludes to a time before our stories of genesis from clay, to a time in which the human had not quite freed itself from the earth.

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Cuerpo-Cueva lI (Cave-Being Il), 2022, water-soluble oil on canvas, 85x120cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

This lively approach to the relation between land and body is not surprising when one considers the place of the artist’s own origin. Díaz Ritson was born just outside of Mexico City in the town Ayapango, underneath the Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl mountains. Referred to locally as the White Woman and the Smoking Mountain, the landforms are said to have been created from the bodies of two young lovers who, running from their disapproving families, eloped to the forest where they ultimately met their death. The snow-capped peaks of Iztaccíhuatl form the profile of a sleeping woman while the volcanic Popocatépetl puffs smoke and ash as he kneels over his dormant lover. It is a storied and living land whose tumultuous origins continue to impact the area’s residents, as Popocatépetl’s love for Iztaccíhuatl is expressed in frequent eruptions.

It is easy to see elements of this tale in Gannets: These Bodies of Rock and Earth , painted prior to the artist’s residency as part of her final undergraduate project. Two kneeling lovers fold into each other, feet pressed to the stone floor of the cave they reside in, each head leaning on the other's shoulder, echoing the courtship ritual of the rock dwelling seabird to which the painting’s title refers. In contrast to the frictive movement of the Cuerpo-Cueva paintings, Gannets possesses a palpable stillness. The figures are anchored to one another, as unwavering as their stone dwelling. Perhaps, like Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, we find them in the process of becoming the land. Mountainous bodies, once flesh and blood, turning to rock and earth.

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Gannets: These Bodies of Rock and Earth, 2021, water-soluble oil on canvas, 145x160cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Within Western philosophy, rock and earth have long served metaphorical roles as the embodiment of fixed and inanimate matter.7 Stories of lovers turned to rock or landform draw from the seeming immovable sublimity of geologic formations to emphasise the endurance of true love. Yet, such characterisations of inorganic materials as fixed and inanimate fail to account for the actual impermanence of these geological forms. As we see in Close and the Cuerpo-Cueva paintings, the Earth exists in a constant animation. Claystone itself is proof of this movement. Beginning its life as exposed rock pushed to mountain tops by plate tectonics or volcanic motion, it is weathered by rain and wind, falling as sediment into valleys and waterways, where it accumulates and solidifies into claystone. Eventually the stone moves beneath the subsurface and, exposed to high temperatures and pressure, will metamorphosise into hard rock. This rock will again return to the Earth’s surface as volcanic magma, beginning the cycle again.

As with the passions of young love and our bodies' skin which ages and regenerates, the Earth’s geology is never truly fixed. Even the most iconic of mountainous peaks, like Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl themselves, are merely momentary solidifications of form in the ongoing circulation of geologic material. Yet such movement takes place over millions of years, at scales far beyond human comprehension and at paces far slower than that of human life. Transforming to earth/Earth the figures of Gannets are, by human timeframes, fixed. Claystone, as both an archiving force of deep time and a mythological source of life’s genesis, unifies these spatial and temporal dualities. Drawing on this material as a metaphorical lens through which to see and interpret the world, Through Claystone Eyes offers a vision of place as both lasting and transitory, tumultuous and immemorial. We are left to juggle its immortal bodies and fleeting hillscapes.

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, Furrowing Wayfarer, 2022, water-mixable oil on canvas, 150x165cm. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

In Furrowing Wayfarer, painted during Díaz Ritson’s time at the Rita Angus Cottage, two figures kneel, pressing their hands to the green earth. Looking downward, the face of the front figure is furrowed like the land around him. He is concerned, perhaps, with his relation to this place. He may wonder how he fits within this land, or perhaps what route he should take over its crevassed topography. He is distinct from the environment around him, though its qualities are echoed in his form. His hands are wrinkled like the earth, his shirt creased like the leaves of the bushes behind him, his skin pale as the sky. Although he may have lost his way over this earth, it is clear that he remains of it.

Though Díaz Ritson’s titles and paintings merge and confuse the boundaries between body and land they are not metaphors but speak frankly to our corporeal embedment in geologic forces. Our bodies are, in the most literal sense, of rock and earth. Our blood contains iron, our tears and sweat are salty, calcium brings strength to our bones. As desire binds lovers, our own bodies tie us deeply to this planet. We may find ourselves, like the figures of Furrowing Wayfarer, a bit lost. Through Claystone Eyes provides the opportunity to look—slowly—and perhaps to kneel down for a minute, and to begin to feel out a new relation to this lively and ancient Earth.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rosie Stack is a Masters student in Art History at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington. She likes writing about the relationship between art and inorganic materials. Her current research focuses on the material ecologies of analogue photography

-

1.

Eleanor Díaz Ritson, “Through My Claystone Eyes,” in Through Claystone Eyes (Wellington: self published artist book, 2022).

-

2.

John Durham Peters, "Space, Time, and Communication Theory," Canadian Journal of Communication 28 no. 4, (2022): 342.

-

3.

Lyell lays out this argument most notably in The Principles of Geology published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833, as discussed by Pascale McCullough Manning, “Charles Lyell’s Geological Imagination.” Literature compass 13, no. 10 (2016): 646–654.

-

4.

For an extended discussion on how geological discoveries influenced 19th century artists and writers see Rosalind Williams, Notes on the Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990).

-

5.

Roger Blackley, Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880-1910. (La Vergne: Auckland University Press, 2018) 264.

-

6.

Díaz Ritson, “Through My Claystone Eyes”.

-

7.

See Steve Mentz, “Stone Voices: Geomaterialism in the Ecohumanities,” Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 6, no. 1 (2018): 118–125.