The Occasional Journal

Local Knowledge

July 2016

-

Editorial

Emma Ng -

Diversifying and moving through the hidden city

Gradon Diprose, Kelly Dombroski -

Don't fucking die today! Putain, ne meurt pas aujourd'hui!

Janet Lilo -

Stitching the Street

Sian van Dyk -

In your belly, a vague place

Ngahuia Harrison -

The Fair in May

Laila O'Brien -

No Stone Unturned

Aliyah Winter, Angela Kilford -

Kinetic Rituals

Balamohan Shingade -

At the still point

Elisabeth Pointon

At the still point

Elisabeth Pointon

For three years, I worked weekends in the deli of a local supermarket wholesaler. As an animal lover, I would make any excuse possible to go and visit the crayfish tank in the seafood department—and as someone who is unjustifiably terrified of fish, to voluntarily spend time amongst so many in order to see the crayfish must’ve meant that something pretty extraordinary was present. I think that at the beginning I was attracted to the crayfish simply because I thought they were cute, particularly their wee little eyes (weirdly enough), but the more time I spent in the crayfish area, the more I started noticing things taking place amongst them—behaviours and tendencies that made me see them as no different to you or me.

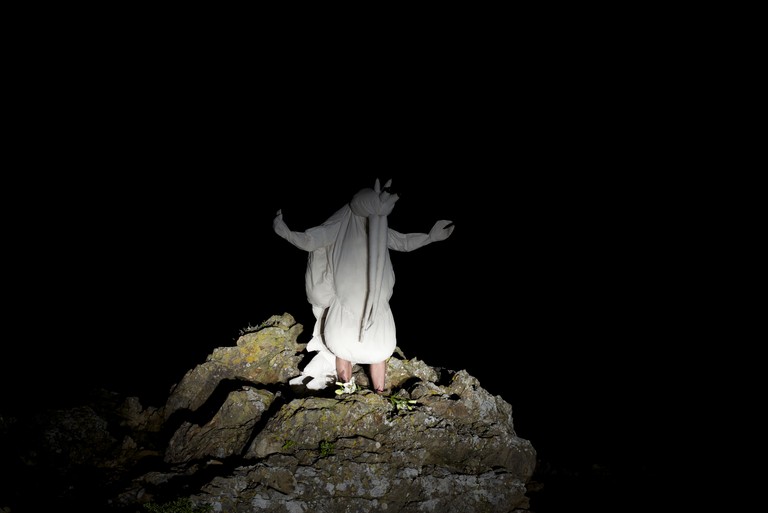

This series of incidents and interactions formed the basis of my recent performance explorations, which used large, white calico crayfish costumes in a variety of different environments and situations to talk to ideas around spiritual freedom and the importance of reconnecting with the present moment and all those who inhabit it.

What follows is three tales that took place over the course of the Christmas period in 2013.

One—

If there is meaning in life at all, there must be meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.1

For the eight or so hours of my shift one Saturday, I regularly frequented the seafood section to check on a one-clawed crayfish, alone in the tank. I noticed that despite its physical limitations it attempted to scramble up the oxygen valve, only to tumble down moments later. Completely awed by its commitment, and its seeming awareness of its plight, I telephoned my father, in tears, to ask for his help to pay for the wee thing, with the hope of releasing it. At the time I only had $40 in my account, and at $99.95 a kilogram I simply could not afford it—and as it always is with my dad, he wholeheartedly and willingly agreed to help, as he too was so touched by its endeavours. The plan was that I would pay the deposit, and he would drive all the way in, pay the rest, collect it and later we would release it back into the sea, together. But there was a whole host of problems, the most obvious being that our crayfish was from a farm—if it survived the atmospheric shift; it would not survive the wild. There was nothing we could really do, and we simply had to resign ourselves to the situation. The crayfish did not.

Two—the following day

We who live in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts, comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken away from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms-to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.2

My interest in and commitment to the crayfish meant I received a fair few sideways looks, and I became the target of many jokes and comments from my colleagues. So much was made of my anxiety over the crayfish, that in order to prepare me for the large Christmas delivery that was expected later on in the day, the ladies who worked in the seafood department telephoned me. I lost it—I could not afford thousands of dollars’ worth of live crayfish, and even if I could, I wouldn’t be able to release them, and keeping them in my bath at home was no better solution, no matter how much I convinced myself it was a good idea.

That day at work for me was rough, and I regularly went to check on those in the tank.

But what happened that evening has to be one of the most beautiful things I have encountered, some sort of bizarre miracle. That night, a crayfish staged an attack on the oxygen valve in the tank, disconnecting it. The next morning, all those crayfish were found dead. They had died together. The repercussions of this act for the business were pretty detrimental, as they were sold on the premise that they were live, and therefore, fresh. I still believe that this was a collective, peaceful resistance, and an almost spiritual one—despite the circumstances the crayfish chose their way. And there is something magnificent in that.

Three–awhile later

Generally speaking, of course any pursuit of art in camp was somewhat grotesque. I would say that the real impression made by anything connected with art arose only from the ghost like contrast between the performance and the background of desolate camp life.3

The Seafood Section is a dismal site, with the live crayfish tank the epitome of what is wrong with the way in which we consume. A bright light illuminates a rectangular case of no more than 1.2 metres in length, highlighting the debris floating around in dirty water, most of it belonging to previous residents. With no means to escape the harsh light, and nothing pertaining to a natural existence, the life of a commercial crayfish is heinous.

It was Viktor Frankl’s writing about ‘art’ in concentration camps that reaffirmed the want for doing something that was meaningful and purposeful for the crayfish. Then it hit me—why not take the crayfish in the tank through a meditation? By this point I had been using my calico Crayfish, performed by my good friend, Kane, in performances derivative of different meditation practices practiced in my family. In my family meditation is as normal as having a cup of coffee in the morning, and sometimes, my dad meditates with our parrot, Del. And if you happen to walk in on the two of them in the middle of one, you see two beings engulfed in and radiating the same absolute stillness, which contrasts phenomenally with the parrot’s usual behaviour.

My boss at the time agreed to let me host a session, as long as it was before the workplace opened to the public at 8am. We arrived at 6.30am. While Kane was preparing himself to become the Crayfish, a pile of salt was placed in front of the tank. Then out came the Crayfish, every step and movement done in complete Zen, as it always is with Kane. My boss had turned off all the main lights in the store, so as to remove any extra distractions, but what was particularly lovely was the way in which the noise of the radio that plays 24/7, the trucks outside, and voices of the morning staff setting up heightened the ensuing stillness in the seafood section.

The Crayfish rested his attention on those in the tank, then the pile of salt, and finally the tool—a large wooden broom which he used to sweep the pile into a flat circle, with a clear centre, moving round and round it, constantly thinning and smoothing the salt, all the while maintaining his distance and hold so as not to allow the feelers to disrupt the formation. When it was just so, Crayfish acknowledged his work, before setting to brushing a pathway into the centre of the circle. Placing the broom to the side, Crayfish moved a little wooden stool into the centre, and sat; carefully arranging his tail underneath him, with his claws clasped on his lap, facing the tank, and began his meditation.

To Kane, my boss, and the lovely fish lady, what happened in the tank was almost beyond belief. The crayfish had all lined up, one by one at the front of the tank, in total stillness, watching—completely at odds with the chaos that was ensuing at the beginning of the session, when the crayfish had been scrambling over one another, pressed up to the glass, and frantically waving their feelers around. Towards the end I witnessed one crayfish climb over another and kick it towards the back of the tank, almost as if to have a seat at the front.4

The behaviours of the crayfish in the tank served as a reminder of what it truly means to be free. Freedom is not a privilege and freedom is not a right—it is a choice that begins with courage, sacrifice, and a stillness of the mind. What is particularly poignant is how this series of events with the crayfish parallel what Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, wrote in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, about the spiritual freedom that came out of his experience of Auschwitz. As Frankl put it:

It is this spiritual freedom—which cannot be taken away—that makes life meaningful and purposeful.5

This concept of spiritual freedom requires work—the initial struggle to detach from the mind’s activity, and to exist in total stillness and silence, which Sri Nisarghadatta Maharaj6 describes as the ‘essence of saintliness’. This total detachment from the past, from the future—from fears, ideas, wants, needs, concerns, desires, and expectations—and total detachment from the chaos of the superficial ego, allows for a true connection with the beauty, power, and potential found in the present moment.

This project has been perhaps the most significant for me, and ideas around what to do next with it are constantly surfacing; and the most interesting to me is staging another meditation, introducing two to three more Crayfish, when there have ever only been two at most, on Tapu te Ranga Motu Island. The idea of the island as a site came to mind while visiting educators at the Marine Education Centre when researching crayfish behaviours. The more I researched the area and the island itself, the more significant and apparent it became to me—the island was once a site of refuge for local Māori, and the area surrounding it is now a refuge for the marine life that inhabit the environment, under the protection of the Department of Conservation. At one point, this island was commonly referred to as Rat Island, when the inhabitants were vermin who could quite easily swim to it. Prior to that it was occupied by a hermit, who had a population of goats which he milked, until he died and the goats were left to destroy the vegetation. In 2009 plans were underway to return it to a place where coastal native plants could thrive in “relative protection”.7

During warfare between northern tribes and Ngāti Ira in the early 19th century, the island became a sanctuary for Tamairangi, the wife of the local chief, and her children. Owing to the lack of fresh water and the inclement weather, they were forced to leave, but evidence of their stone-walled pa is still noticable.

Bruce Stewart, a local Māori elder says the island was also once called Patawa, and Kupe climbed it to get a better view of a wheke, a giant octopus.

The salvation of man is through love and in love.8

Now the island is free from activity; a physical still point—what happens when that stillness is tapped into and resonated outwards? This place has become my homing beacon in a sense, and when I become engulfed by overwhelming anxiety, which happens from time to time, the only remedy or way out is to stand at my still point, and remember that we only recognise that which we can see in ourselves. I am the Crayfish, but aren't we all?

About the Artist

Elisabeth Pointon is based in Wellington, New Zealand, currently undertaking her Masters of Fine Arts at Massey University. Elisabeth works primarily in live performance and public intervention, embracing ideas of spiritual freedom, and the importance of reconnecting with the present moment and all those who inhabit it. Recent works have included meditations with live crayfish in tanks at local seafood suppliers, conversations with dormant lighthouses, and taking to the streets in a modified quadricycle-cum-campaign vehicle as and co-pilot of The Welcoming Party, in their work Complimentary Service.

-

1.

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (London: Rider, 2004), 76.

-

2.

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (London: Rider, 2004), 75.

-

3.

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (London: Rider, 2004), 53.

-

4.

I relayed the events to my dad, and received an email reply, which encapsulates all that these works are about. In regards to a conversation with his meditation group he wrote—

Now with regard to Crayfish’s last performance in front of the crayfish tank at your work, I just happened to mention it to the group, more-or-less in passing about five minutes before our meditation session began. Everyone was intrigued, and wanted to know more.

I told them that you wanted to honour the crayfish for their inspiration for what you considered to be your most important work to date –that you went in at 6.30 in the morning when no one would be around because it was for the crayfish alone.

Crayfish began as usual to create a salt circle, but this time in complete silence, broke into it and because there was no music to spin to he simply sat on a small wooden stool at the circle’s centre, at “the still point of the turning world” (–T.S. Elliot), and meditated for some time. What we took from that is that we cut ourselves off from my Self, we create a barrier, a circle that prevents us from being one with all.

It reminded me that we can only break through the barriers of self-created bondage by conscious, deliberate action.

With that, Crayfish moved into the centre of the circle, paused and slowly started spinning, signifying the connection between heaven and earth, between myself and the One that I am in truth the One- the still point of the turning world.

All this was beautiful in itself, but what no one took into account, or even considered a possibility was the effect that it had on the crayfish in the tank.

During the set up they were moving around the tank, some a little more energetically than others, but as the performance got underway the absolutely unexpected, perhaps to some, unbelievable happened.

Gradually, one by one the crayfish began to quieten down and by the time Crayfish himself was sitting down meditating they were completely still. But here is the miracle-all the crayfish were facing him, watching the performance, perhaps even meditating with him. Whatever else you might say-communion, that coming together as one was the unlooked for and totally unexpected outcome.

Believe it or not Elisabeth the performance became very much the focus of our discussion, that in silent-being-awareness in the complete absence of the ego (the salt circle) we enter into that “still point of the turning world” and the unity (the communion), the Oneness with all is experienced. The discussion went further, the performance highlighted not only our connectedness to all things but our responsibility to care, and therefore to love all things. This was summed up with a quote from Nisarghadatta Maharaj; “do not undervalue silent-being-awareness, all blessings flow from it”.

-

5.

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (London: Rider, 2004), 75-76.

-

6.

Sri Nisarghadatta Maharaj was an Indian Guru of Nondualism. His 1973 book I am that, translated by Maurice Frydman, is widely cited for his discussion around the mind’s construction of the ego.

-

7.

The Dominion Post, "The jewel that is Rat Island," January 28, 2009.

-

8.

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (London: Rider, 2004), 49.